-

Epidemics of emerging and neglected infectious diseases are severe threats to public health and are largely driven by the promotion of globalization and by international multi-border cooperation. Mosquito-borne viruses are among the most important agents of these diseases, with an associated mortality of over one million people worldwide (1). The well-known mosquito-borne diseases (MBDs) with global scale include malaria, dengue fever, chikungunya, and West Nile fever, which are the largest contributor to the disease burden. However, the morbidity of some MBDs has sharply decreased due to expanded programs on immunization and more efficient control strategies (e.g., for Japanese encephalitis and yellow fever). Nevertheless, the global distribution and burden of dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika fever are expanding and growing (2-3). Similar to the seemingly interminable coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic sweeping across the globe since the end of 2020, MBDs could also spread at an unexpected rate (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1) and cause great economic damage.

Virus Vector Vertebrate host Distribution (year) ZIKV Armigeres subalbatus

Culex quinquefasciatus

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus

Anopheles sinensisHuman Guizhou (2016); Jiangxi (2018); Yunnan (2016) TMUV Cx. pipiens

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus

Cx. annulusDuck

Goose

Chicken

Sparrow

PigeonAnhui (2013); Beijing (2010); Chongqing (2013); Fujian (2010); Guangdong (2011–2015); Guangxi (2011); Hebei (2010); Henan (2010); Hubei (2018); Inner Mongolia (2017); Jiangsu (2010, 2012); Jiangxi (2010); Shandong (2010, 2011, 2012, 2016); Shanghai (2010); Zhejiang (2010–2016); Yunnan (2012); Sichuan (2013); Taiwan (2019) LNV Aedes flavidorsalis

Ae. caspius

Cx. pipiens

Cx. modestus

Ae. dorsali

Ae. vexansMice Beijing (2014); Gansu (2011); Jilin (1997); Liaoning (2012); Qinghai (2007); Shanxi (2007); Xinjiang (2005, 2006–2008, 2011) GETV Cx. tritaeniorhynchus

Ar. subalbatus

Cx. pseudovishnui

Cx. fuscocephala

Cx. annulus

An. sinensis

Cx. pipiensHorse

Swine

Cattle

Blue foxAnhui (2017); Gansu (2006); Guangdong (2018); Guizhou (2008); Hainan (1964, 2018); Hebei (2002); Henan (2011); Hubei (2010); Hunan (2017); Inner Mongoria (2018); Jilin (2017, 2018); Liaoning (2006); Shandong (2017); Shanghai (2005); Shanxi (2012); Sichuan (2012, 2018); Taiwan (2002); Yunnan (2005, 2007, 2010, 2012) CHAOV Ae. vexans

Cx. pipiensLiaoning (2008); Inner Mongolia (2018) AeFV Ae. albopictus Hubei (2018); Shanghai (2016); Yunnan (2018) CxFV Cx. pipiens

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus

An. sinensis

Cx. modestusGansu (2011); Henan (2004); Hubei (2018); Inner Mongolia (2018); Liaoning (2011); Shaanxi (2012); Shandong (2009, 2012, 2018); Shanghai (2016, 2018); Shanxi (2012); Taiwan (2010); Xinjiang (2012) QBV Cx. tritaeniorhynchus

Cx. pipiens

An. sinensisHainan (2018); Hubei (2018); Inner Mongolia (2018); Shandong (2018); Shanghai (2016, 2018) Abbreviations: AeFV=Aedes flavivirus; CHAOV=Chaoyang virus; CxFV=Culex flavivirus; GETV=Getah virus; LNV=Liao ning virus; QBV=Quang Binh flavivirus; TMUV=Tembusu virus; ZIKV=Zika virus. Table 1. Vectors, hosts, geographic distributions, and collection years of emerging mosquito-associated viruses in China (2010–2020).

HTML

-

The Zika virus (ZIKV) causes a traditional mosquito-borne enzootic disease and was first identified in rhesus monkeys in Uganda in 1947, subsequently spreading in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Islands, and expanding to Brazil in May 2015 (4). China seemed successful in keeping the Zika pandemic at bay with only a few imported cases (5). However, ZIKV was isolated in mosquitoes from Yunnan, Guizhou, and Jiangxi from 2016 to 2018 (6), and 1.8% of healthy individuals in Nanning, China were positive for the ZIKV antibody (7). This suggests the existence of the natural circulation of ZIKV between mosquitoes and humans in China even before the international public health emergency. The sudden outbreak of egg drop syndrome caused by the Tembusu virus (TMUV) quickly swept the coastal provinces and neighboring regions in 2010, resulting in severe economic loss in the poultry industry (8). To date, records of TMUV have covered 18 provinces in China, and are mainly comprised of reports from the last decade (9). Similarly, the Getah virus, which is mainly transmitted between mosquitoes and domestic livestock, has been spreading across China since 2010 (10), with an outbreak on a swine farm in Hunan in 2017 (11). Moreover, despite having a relatively short history (first detected in 1997), the Liao ning virus (LNV) has been recorded in most of Northern China, including Beijing. It was initially thought that the virus was specific to China, until the virus was isolated from 4 genera of mosquitoes collected along coastal regions of Australia during 1988 to 2014, with a characteristic insect-specific phenotype (12). By contrast, the Chinese isolates can be replicated in mammalian cell lines and cause viremia and massive hemorrhage during re-infection of mice (13).

-

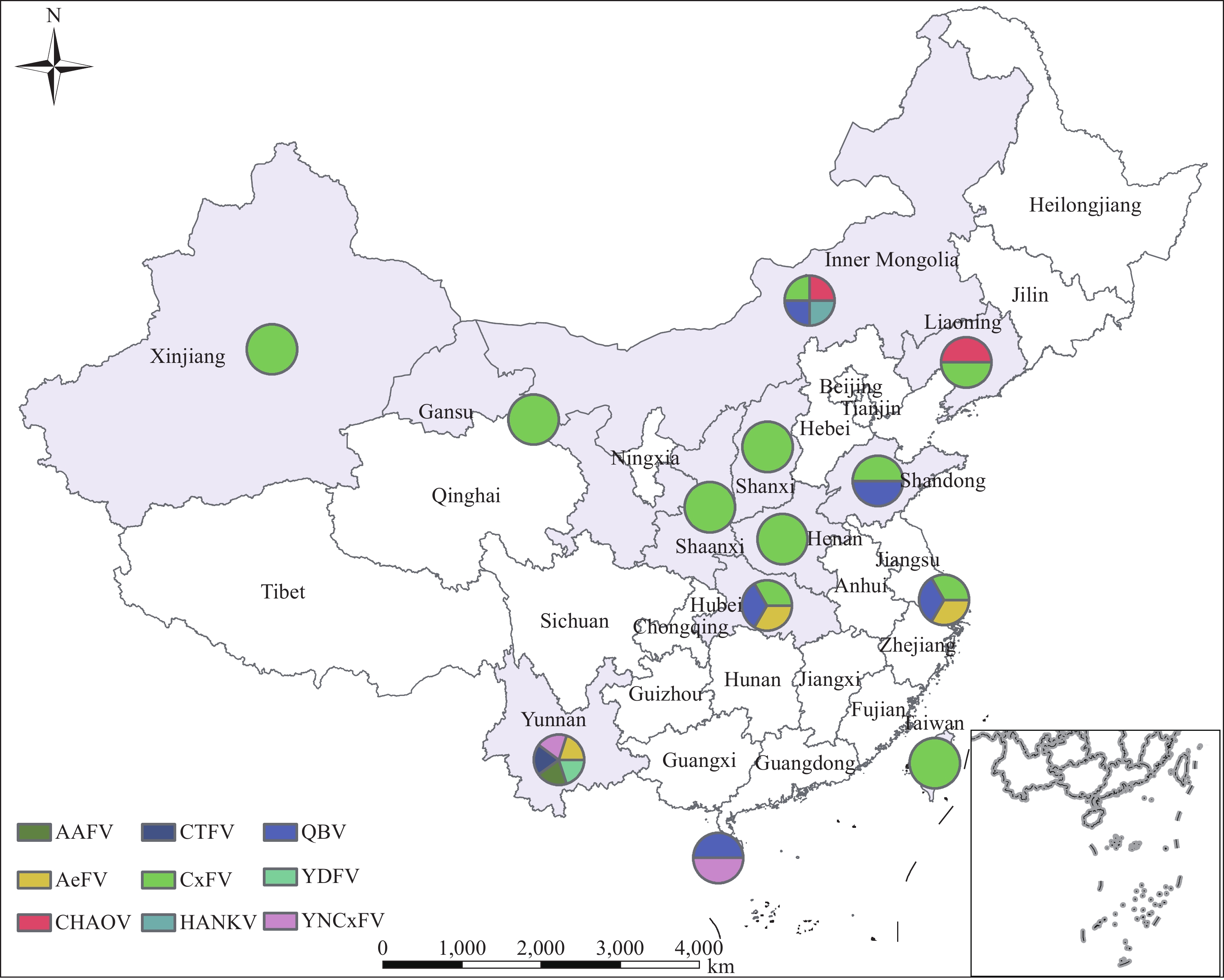

Aside from the mosquito-borne zoonotic and potentially pathogenic viruses, the increasing discovery of insect-specific flaviviruses (ISFVs) in the last decade is also worthy of attention (Figure 1). ISFVs, which are specific to insects, have both horizontal and vertical transmission routes, have diverse host relationships, and have a wide geographic distribution. This group can be divided into monophyletic classical ISFVs (cISFVs) and dual-host ISFVs (dISFVs), with the latter being more closely related to mosquito-borne pathogenic flaviviruses (MBPFVs) speculated to have lost their ability to infect vertebrate cells during their evolution (14). There are three common cISFVs hosted by medically important mosquitoes: the Culex flavivirus (CxFV), the Quang Binh virus (QBV), and the Aedes flavivirus (AeFV) (10,15). The distribution and host range of the Hanko virus (Inner Mongolia, 2018), the Yunnan Culex flavivirus (Yunnan, 2009; 2018), the Culex theileri flavivirus (Yunnan, 2018), and the Yamadai flavivirus (Yunnan, 2018) in China are relatively localized (10,16). In some instances, a high prevalence of ISFVs have been observed in the field, such as QBV (21.53/1000) in Cx. pipiens in Jining, CxFV (61.25/1000) in Cx. tritaeniorhynchus in Sanya, and AeFV (33.93/1000) in Aedes albopictus in Songjiang District, Shanghai (10,15). By contrast, the distribution and host range of dISFVs are narrower than that of cISFVs. The two dISFVs recorded in China, the Chaoyang virus (Liaoning, 2008; Inner Mongolia, 2018) and the Donggang virus (Liaoning, 2009, unpublished in China), are transmitted by Ae. vexans and Cx. pipiens and by Aedes mosquitoes, respectively.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Geographic distribution and diversity of insect specific flaviviruses in China by 2020.

Abbreviations: AAFV=Anopheles associated flavivirus; AeFV=Aedes flavivirus; CHAOV=Chaoyang virus; CTFV=Culex theileri flavivirus; CxFV=Culex flavivirus; HANKV=Hanko virus; QBV=Quang Binh flavivirus; YDFV=Yamadai flavivirus; YNCxFV=Yunnan Culex flavivirus.

-

Since vaccines for the majority of MBVs are unavailable, vector control is the major route for routine control and epidemic disposal. However, the intensive use of insecticides in agriculture and pest management has resulted in the development and increase of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Therefore, it is urgent to develop novel control strategies and tools. Biological control is the traditional research hotspot, as it is sustainable and environmentally friendly. Bacteria (Bacillus thuringiensis, Wolbachia) have been wildly used in the field. By contrast, the use of fungi (Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana) and viruses (Densovirus) as alternative mosquito control agents remains at the laboratory or semi-field stages. Further studies on ISFVs have led to the discovery of their natural, physical, and ecological characteristics, as well as their phylogenetic status, and these clues indicate the potential of ISFVs as a novel interventional tool for vector control, most likely based on the mechanism of superinfection exclusion (17). Moreover, because of their phylogenetic similarity, it seems that dISFVs have a greater potential to inhibit the replication of MBPFVs than cISFVs. Superinfection exclusion can occur between closely related viruses; however, more distantly related viruses do not generally interfere with each other (18). In practice, infection with cISFV and CxFV may reportedly increase the West Nile virus (WNV) infection rate, possibly through facilitation of secondary infections with similar agents by the reduction of immune recognition (18), and because prior infection with cell-fusing agent viruses may reduce the dissessmination titer of ZIKV and dengue virus (DENV) both in vitro and in vivo. Other studies have also shown that during instances of prior infection with dISFV, the Nhumirim virus will suppress subsequent replication of mosquito-borne flaviviruses associated with human diseases, including WNV (19), ZIKV, and DENV (20). Nevertheless, further studies are necessary to help us arrive at a consensus regarding whether or not the presence of ISFVs can interfere with infection by MBPFVs, which could also subsequently alter the transmission capacity of certain vector populations for several vector-borne diseases. It is also important to more thoroughly analyze the maintenance cycle of ISFVs and how they escape the host immune system. Furthermore, we should pay more attention to how ISFVs are apparently unable to affect the health of birds, domestic animals, and humans. It is noteworthy that these viruses are carried by medically important mosquitoes and likely to attack vertebrate immune system when vertebrate innate immunity pathways are disabled by known pathogenic flaviviruses (21), which represent a potential threat to both human and animal health.

-

Emerging and preexisting MBVs are spreading globally at an unexpected rate. MBD surveillance may have been constrained by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has drawn the most attention with regards to public health, but hampers the expansion of MBVs because of restrictions in international travel. Routine mosquito surveillance and screening for mosquito-borne pathogens can be early indicators for local disease transmission and outbreaks. These practices also highlight that wide-ranging, systematic, and continuous molecular monitoring of mosquito-borne circulating viruses in vectors is urgently needed. This monitoring would provide a comprehensive understanding of virus diversity, geographic distribution, evolution, shifts in circulating genotypes, and infection rates in China and other neighboring countries and allow accurate and timely estimations of the true disease burden and prevalence of emerging/re-emerging and known mosquito-borne pathogens. This is essential to support the decision-making process regarding appropriate prevention and control strategies in China, neighboring countries, and countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiatives. Moreover, a close watch on the dynamics of mosquito insecticide resistance, alternative insecticides in certain areas, and the proper use of insect growth regulators or biocontrol approaches for integrated vector control programs should also be considered to mitigate and slow the spread and impact of insecticide resistance development in disease vector populations. The biodiversity, widespread presence, and variety of mosquito host species of ISFVs in nature shed light on means of indirect protection against the dissemination of MBVs. Ultimately, there is also an urgent need to develop an MBV vaccine using strains that are prevalent in the field to reduce the increasing health risks posed by MBVs.

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: