-

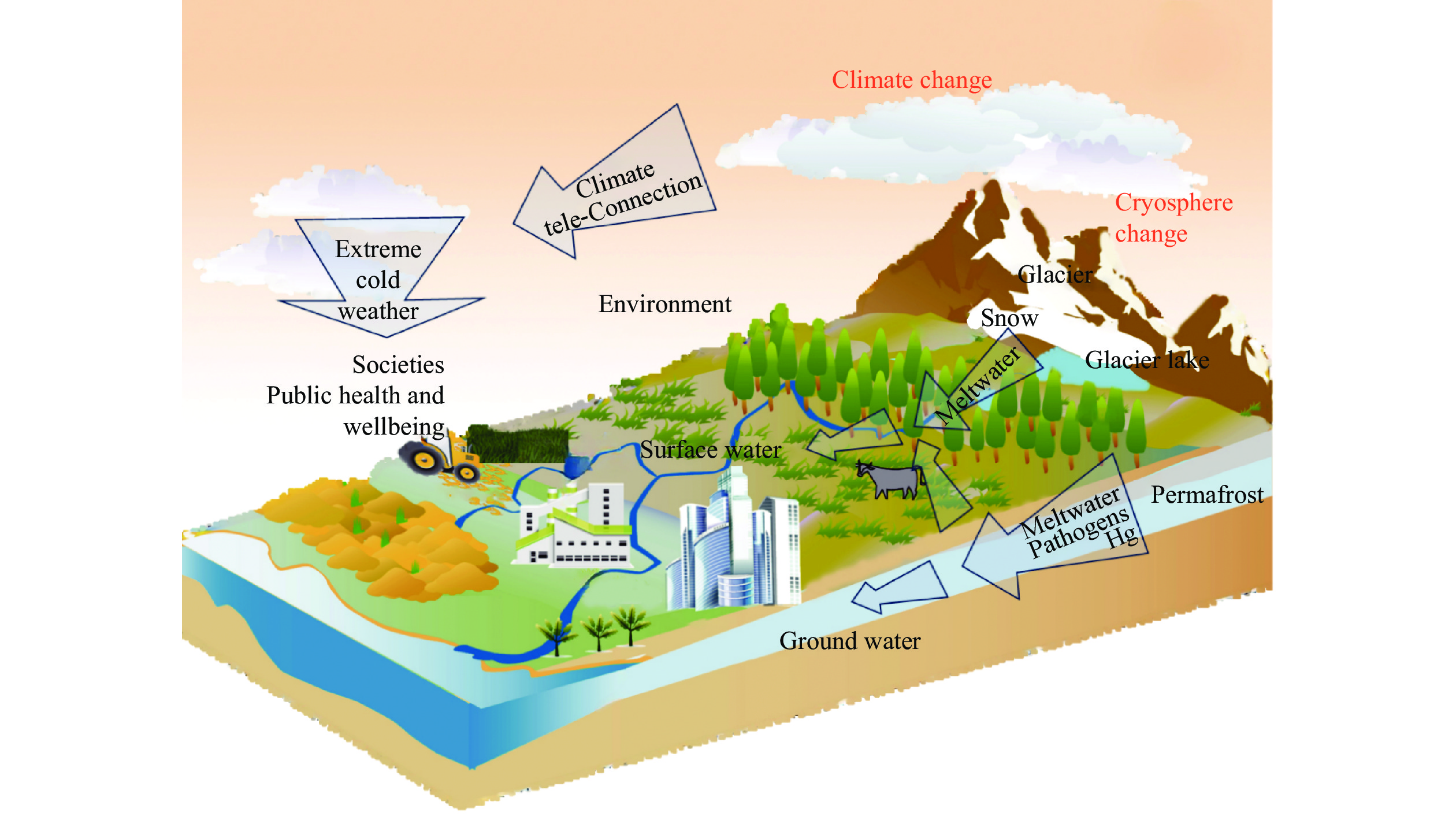

Climate change induces far-reaching cascading effects on ecosystems, economies, and human health. Among the most vulnerable components of the Earth system is the cryosphere, where water is frozen, encompassing glaciers, snow cover, permafrost, ice sheets, sea ice, lake ice, and other frozen formations. The cryosphere typically exhibits seasonal variations, accumulating and retreating in recurring patterns following freeze-thaw cycles over years. Climate-driven retreats in the cryosphere can generate both adverse and beneficial cascading effects on environments and societies (1), with profound implications for public health, as illustrated in Figure 1. However, our understanding of how cryosphere changes impact public health remains insufficient, hindering the development of effective risk mitigation policies. We aim to bridge this knowledge gap by raising awareness and fostering new perspectives to strengthen public health risk mitigation strategies in a rapidly changing cryosphere.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Cascading effects of cryosphere change due to global warming on environment and societies in terms of public health and wellbeing.

The cryosphere generates natural hazards that can severely impact human societies. For example, glacier lake outburst flooding (GLOF) (2-3), caused by deterioration and eventual breach of moraine- or ice-dammed glacial lakes, can lead to catastrophic damage to downstream communities. Global warming exacerbates not only geohazards but also climate-related hazards associated with cryosphere changes, threatening human lives. The increasing activity of cold fronts moving from high latitudes to mid-latitudes — resulting from a weakened polar vortex associated with Arctic warming (4) — can trigger severe winters and snowstorms in mid-latitude regions (5-6), leading to elevated mortality and morbidity risks.

The cryosphere also provides essential services that benefit societies, collectively known as cryosphere services (1). The cryosphere functions as a “reservoir of solid water” that serves as a critical source of freshwater; its freeze-thaw dynamics play vital roles in regulating climate and hydrological cycles; and its cold environments support essential ecosystems in high-latitude and high-altitude regions. Additionally, the cryosphere embodies significant spiritual, heritage, and recreational values. However, global warming is profoundly altering both the quantity and quality of cryosphere services, consequently impacting the wellbeing of human societies.

The intensification of cryosphere hazards and deterioration of cryosphere services resulting from climate change can produce substantial cascading effects on human health (7), particularly for populations closely connected with the cryosphere in polar and high mountain regions, as well as in semiarid or arid downstream areas (8). The extreme weather and climate events in winter, influenced by teleconnected atmospheric circulation systems, extend cryosphere change impacts to regions even beyond these directly affected areas (5-6).

-

Rapid climate change is driving unprecedented transformations in the cryosphere. Globally, glaciers have lost 273±16 gigatonnes (Gt) of mass annually from 2000 to 2023 (9–10). In High Mountain Asia, including Central and Northern Tien Shan as well as Eastern Pamir, glacier mass loss rates have progressively accelerated since the 1960s (11). While rising temperatures initially enhance glacier meltwater supply, this trend reverses once glacier mass diminishes beyond a critical threshold, ultimately leading to long-term freshwater availability decline.

Concurrently, snow cover has decreased in the Northern Hemisphere spring since 1950, particularly in North America, which exhibits a significant declining trend of 46 Gt per decade in March snow mass (12). In the European Alps, snow depth has declined at 8.4% per decade, accompanied by snow cover reduction at 5.6% per decade during 1971–2019, resulting in snow cover duration 36 days shorter than the six-century long-term mean (13). The warming climate not only reduces snow cover extent but also advances the timing of snowmelt (14). These changes subsequently diminish snowmelt water availability and alter annual snowmelt dynamics (15), affecting various ecological (16) and agricultural irrigation requirements (17).

Simultaneously, permafrost temperatures have increased globally by approximately 0.29 °C during the period from 2007–2016 (18). In the high-latitude Arctic, warming rates can reach up to 1°C per decade (19). Warming permafrost accelerates the release of soil organic carbon and nutrients, along with various toxic substances. Under high emission scenarios, projected mercury (Hg) release from thawing permafrost is expected to elevate Hg concentrations in Yukon River fish beyond the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) guidelines by 2050 (20).

The Arctic continues to warm at more than twice the global rate (21). Compounded by declining sea ice and Arctic warming, the Northern Hemisphere has increasingly experienced extreme cold weather events (5,22), associated with a stratospheric polar vortex that has weakened over the past three decades, driving cold polar air masses toward mid-latitude regions (6). It is reasonable to conclude that the increasingly warmer Arctic and diminishing sea ice could further exacerbate stratospheric polar vortex variability, subsequently increasing the likelihood of extreme winter climate events in mid-latitude regions.

-

Evidence demonstrates that populations worldwide face unprecedented threats to their wellbeing, health, and survival from rapidly changing climate conditions and the subsequent increase in frequency and intensity of hazards, including floods, heatwaves, fires, and storms (23). Between 1961–1990 and 2014–2023, 61% of global land area experienced an increase in days with extreme precipitation, consequently elevating risks of flooding, infectious disease transmission, and water contamination (24). A comprehensive epidemiological analysis revealed that mortality risks increased and persisted for up to 60 days following flood events, with all-cause, cardiovascular, and respiratory mortality increasing by 2.1%, 2.6%, and 4.9%, respectively (25).

The changing cryosphere is generating increasingly severe hazards, such as GLOF and intensified snowmelt flooding during spring. In 2021, a catastrophic debris flow triggered by an avalanche involving approximately 27×106 m3 of rock and ice resulted in devastating consequences across Himalayan regions of India (26–28). Extreme winter weather conditions, including snow storms induced by shifting stratospheric polar vortex patterns, affected 8.685 million people in January 2018 in China (29). During 2000–2019, cold spells contributed to 205,000 annual excess deaths globally, with Europe experiencing the highest mortality burden (30). More recently, in January 2025, historic snow storms swept across North America and Europe, triggering record-breaking low temperatures and hundreds of traffic accidents. These increasing cryospheric hazards substantially elevate risks of injury, morbidity, and mortality, comparable to the adverse impacts of other climate and hydroclimatic hazards previously described.

-

Permafrost harbors diverse microbial communities (31). Thawing permafrost can expose preserved remains of infectious disease victims (both human and animal) (32). If viral pathogens maintain infectivity in permafrost, thawing could potentially trigger disease outbreaks (33) through three distinct pathways (34). The first involves reintroduction of human viral pathogens, such as influenza and smallpox, from thawing graves and mass burial sites. The second concerns reintroduction of viruses from thawed wildlife or domestic animal remains in permafrost, which could transmit directly to humans or infect animals before jumping to humans. The third pathway involves spillover of permafrost viruses with microbial hosts, including microeukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea, to humans or animals following permafrost thaw. Evidence suggests pathogenic microorganisms can emerge from thawing permafrost and cause disease. For example, in July-August 2016, a massive anthrax outbreak in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) occurred on the Yamal Peninsula, Northwest Siberia in Russia, resulting in one human fatality, dozens of illnesses, and thousands of reindeer deaths (35–36). In 1991, Russian experts discovered a wooden vault containing frozen victims of a nineteenth-century smallpox epidemic in a small village near the North Pole (37). This discovery raised concerns about the possible resurgence of smallpox following permafrost thaw (38).

Beyond the revival of ancient pathogens, thawing permafrost can release toxic substances (i.e., Hg) (20) and legacy hazardous industrial wastes (39) trapped in ice, contaminating soil and water supplies and impacting food webs. The Arctic contains a substantial reservoir of Hg, with approximately 597,000 Mg accumulated in the 0–3 m depth of permafrost soils (40). Exposure to Hg poses significant adverse health effects across life stages, including neurodevelopmental impairment in children and cardiovascular diseases in adults (41).

-

Exposure to extreme weather and climate events significantly compounds mental health burdens, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (42). These psychological impacts manifest through direct pathways, such as infrastructure loss, displacement, and violence, as well as indirect mechanisms, including landscape degradation, protracted economic recovery, and perceived environmental instability (43).

The diminishing provisioning services of the cryosphere constrain meltwater supply, adversely affecting freshwater availability and quality for communities and economies. In high-altitude regions such as the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (44), insufficient irrigation supply can compromise both food production and nutritional quality (45–47), precipitating food insecurity and subsequent malnutrition (48). Concurrently, diminished water availability can trigger regional livelihood crises and potential conflicts (49), fostering intergroup competition that generates anxiety and psychological distress (50).

Furthermore, the decline in ice-dependent recreational practices, including tourism, winter sports, and pilgrimages, restricts access to nature-based stress relief mechanisms, particularly in high-latitude and high-altitude regions (51–52). Deteriorating cultural services can also undermine indigenous identity and traditions, catalyzing mental health challenges. For instance, in the Qullqipunqu Mountains of Peru, glacier retreat and restrictions on candle use during pilgrimages have profoundly disrupted religious practices and eroded glacier-related cultural values among native adherents (53).

More comprehensively, escalating cryosphere hazards impact overall human wellbeing, which encompasses multiple dimensions beyond physical health, including safety, place attachment, self-identity, and social belonging (54). This necessitates a paradigm shift in risk mitigation strategies toward a holistic approach centered on people, communities, and societies, rather than exclusively emphasizing food production and economic development that essentially support human wellbeing.

-

Global efforts to reduce carbon emissions and mitigate climate change, such as the Paris Agreement, are currently underway. However, achieving the goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, with efforts to restrict the increase to 1.5 °C by the end of the 21st century, faces mounting challenges. Recent data indicate that global mean surface temperature exceeded 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels for 12 consecutive months through June 2024, signaling an earlier breach of the Paris Agreement threshold (55). This development has profound implications for the cryosphere, which may undergo more rapid changes with subsequent intensification of public health risks.

Despite these concerning trends, public awareness and preparedness for these changes remain insufficient. Developing public health adaptation strategies to minimize risks associated with cryosphere change has become increasingly imperative. These strategies necessitate targeted, proactive measures that integrate broad climate resilience, healthcare infrastructure enhancement, and community preparedness, specifically addressing the escalating risks from cryosphere degradation. Implementation requires three critical steps: first, improving awareness among the public, governments, and health sectors about the health risks posed by cryosphere changes; second, developing climate adaptation action plans for public health that explicitly address cryosphere-related risks; and third, initiating targeted investments and implementation of public health adaptations, driven by either government policies or market opportunities. For example, to control and prevent the revival of ancient pathogens associated with thawing permafrost, the primary strategy should focus on mitigating GHG emissions, so ambitious climate action is imperative. Additionally, clinicians need to be aware that pathogenic microorganisms may emerge from thawing permafrost and cause disease. Thus, any suspected cases should be checked for their exposure to thawing permafrost. Furthermore, vaccines against ancient pathogens (e.g., smallpox) should be kept just in case of their possible comeback.

To facilitate progress in adaptation, it is essential to understand the potential hazards to public health posed by both geohazards and climate hazards emerging from rapid cryosphere changes in response to global warming. We must advance knowledge not only about the dynamics of cryosphere changes but also their immediate and long-term implications for public health across different regions and through various causal pathways. This necessitates interdisciplinary collaboration across diverse fields and international cooperation, especially in transboundary regions such as the Arctic and Tibetan Plateau.

An effective approach to adapting to cryosphere change and mitigating public health risks requires comprehensive efforts beyond environmental and public health sectors. In addition to strengthened global climate mitigation actions, the integration of proactive public health adaptation strategies centered on people, communities, and societies, fostered by improved water resource management, reinforced climate and environmental monitoring systems, and enhanced disaster risk management, will collectively yield substantial benefits for human health, and after all, for societal wellbeing.

HTML

Cryosphere Change

Impacts on Public Health

Growing impacts of cryosphere hazards under warming climate – increasing risks to public health:

Revival of ancient pathogens and release of toxic substance from thawing permafrost – emerging risks to public health:

Increasing cryosphere hazards and relinquished cryosphere services – threats to people’s wellbeing:

Strategies for Adaptation to Mitigate Public Health Risks to Cryosphere Change

-

This research involves no ethical concerns as it does not include human/animal subjects or sensitive data.

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: