-

The frequent simultaneous occurrence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and heatwaves is a reminder that the combination of these 2 events is a global health issue. However, studies rarely explored how the public responds to this compounded risk of heatwaves and COVID-19. This study performed a retrospective survey in Beijing, China during the summer of 2020 to measure how the public changed their perceptions and behaviors to cope with this compounded risk. In periods of heatwaves, the proportion of people primarily concerned with COVID-19 reduced by 9.4% and the proportion of individuals continuously wearing masks decreased by 20.6%. Heatwave exposure corresponded to a 58% (95% CI: 50%–65%) decrease in the likelihood of wearing masks and a 41% (95% CI: 21%–56%) decrease in continuously taking well-ventilated public transportation. Heatwaves can disturb public compliance to COVID-19 preventative measures, and as the global incidence of COVID-19 is still on the rise, heatwave events in summers are a looming challenge in public health. This study could provide support to public health authorities to better prepare and implement optimal disease prevention strategies to address the compounded risks.

Heatwaves have occurred simultaneously with the COVID-19 pandemic in several countries worldwide during the past year (1-3), including a coinciding of the two during the current COVID-19 emergency in India with a rolling average of 378,000 new cases a day (4). People naturally tend to take actions to cool down to cope with extreme heat, such as dressing lightly and taking air-conditioned public transportation, which sometimes counters key COVID-19 prevention strategies such as wearing masks (5). Considering the increasing probability of heatwaves and COVID-19 epidemics occurring simultaneously, understanding public perceptions and responding to compound risks is crucial for promoting sustainable actions to adapt to climate change and minimizing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (6).

From May to September 2020, China experienced frequent heatwaves and announced 18,992 high-temperature warnings across the country. On June 11, 2020, an outbreak of COVID-19 started from the Xinfadi Wholesale Market in Beijing Municipality, which was followed by strict disease control actions and widespread communication to citizens to strengthen individual prevention. Simultaneously, Beijing was suffering from frequent heatwave events (Supplementary Figure S1), and 3 high temperature warnings (over 35 ℃) were issued for June 6–8, June 14–16, and July 23–25. Since the Chinese government has implemented strict measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (7) and has guided the public on implementing individual protective measures, mainly including wearing masks, staying in well-ventilated spaces, avoiding public gatherings, and maintaining personal hygiene, this study in Beijing provided insight on how people change their behaviors to respond to heatwaves during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A retrospective survey was conducted at the end of the Xinfadi COVID-19 outbreak in Beijing in early August 2020 using an online survey platform. Two periods of the survey were conducted to include heatwave and non-heatwave periods, and the identical questions on individual risk perceptions and COVID-19 prevention behaviors were investigated (Supplementary Table S1). First, based on the psychological measurement paradigm method (8), 4 factors measuring perceptions, including knowledge, concern, severity, and controllability, were investigated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very). Risk perception dominance was then defined based on the scores of each perception factor question and was adopted to compare the risk perceptions of COVID-19 and of heatwaves. The study population were then categorized into the following 3 groups: 1) heatwave risk dominance (higher scores for heatwave related questions); 2) COVID-19 risk dominance (higher scores for COVID-19 related questions); and 3) equal dominance (equal scores for both of heatwave and COVID-19). The proportions of the three types of perception dominance were then calculated. Second, we considered two critical individual prevention behaviors against the infection of COVID-19: wearing masks and taking well-ventilated public transportation (a choice between taking enclosed air-conditioned public transportation or well-ventilated public transportation without air conditioner, which include buses whose windows can be opened manually). These two behaviors were measured by three choices, including “1=Continuously doing”, “2=Sometimes doing” and “3=Never doing” (see Supplementary Table S1). In addition, a fourth option was given when asked about taking well-ventilated public transportation, “4=Ignore this issue”; respondents who selected this option were excluded from the analysis (about 17.6% of the study population).

Based on a three-step quality control process, 1,000 valid responses were ultimately obtained. This study first compared differences in the proportion of risk perception dominance and individual choices of prevention behaviors between heatwave and non-heatwave periods using the chi-squared tests. Logistic regression models were then used to analyze the impact of exposure to compound heatwaves on individual COVID-19 prevention behaviors after controlling for demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, occupation, and income) in the total study population and different subgroups, in which we reorganized the outcome choices as a binary variable in two ways (Y1: “Continuously doing”=1, others including “Sometimes doing” and “Never doing”=0; Y2: “Never doing”=1, other including “Sometimes doing” and “Continuously doing”=0) to test the effect of heat exposure (binary variable, “heatwave period”=1, “non-heatwave period”=0) on individual adherence to COVID-19 preventions. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to present the results. Details have been presented in Supplementary Material. All the analyses were conducted using the R statistical software (version 4.0.3, the University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand).

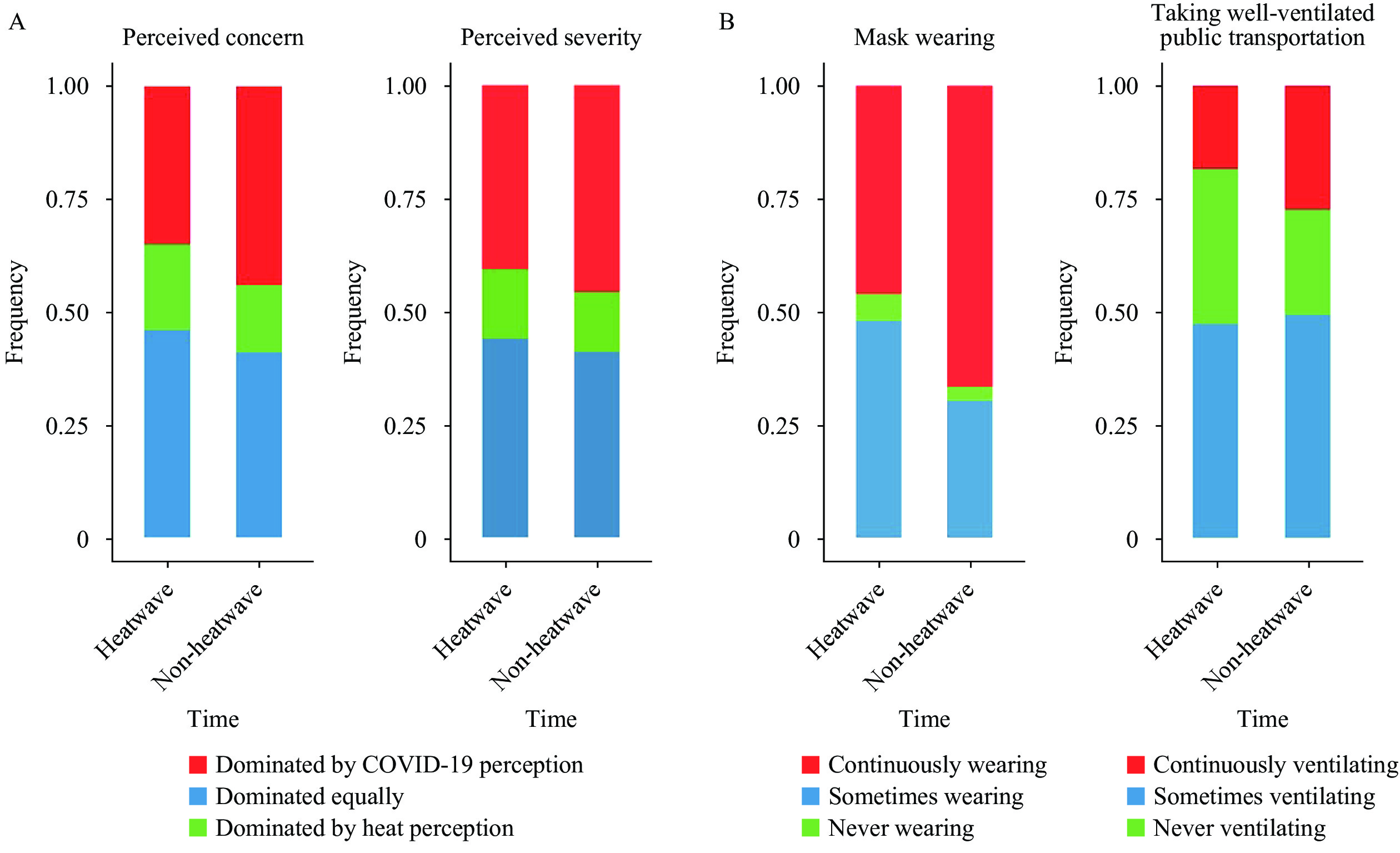

The sample population was representative of the city’s population structure in terms of gender and income but included less population over 40-years old and more high-level educated population (Table 1). Results of the chi-square test indicated significant differences in perception dominance and choices of prevention behaviors between heatwave and non-heatwave periods: as Figure 1A indicated, compared to the non-heatwave periods, the proportion of people expressing concern dominated by the risk of COVID-19 were reduced by 9.4% in heatwave periods, while people expressing concern dominated by heat risk increased by 3.9% during heatwave periods (χ2=131.90, P<0.001); for masking wearing behaviors in Figure 1B, individuals who continuously wore masks decreased by 20.6% in heatwave periods (χ2=87.23, P<0.001); for taking well-ventilated public transportation, continuously taking well-ventilated public transportation decreased by 9% (χ2=20.86, P<0.001).

Item Number of participants Sample proportion Beijing population proportion* P value† Gender Men 500 50.0% 50.9% 0.85 Women 500 50.0% 49.1% Age (years old) ≤30 513 51.3% 30.9% <0.001 30–40 402 40.2% 20.7% ≥40 85 8.5% 48.4% Education level Senior high school and below 275 27.5% 61.1% <0.001 University and above 725 72.5% 38.9% Occupation Office worker 512 51.2% / Face to face service staffs 171 17.1% / Self-employed 196 19.6% / Other (including students and the retired) 171 10.9% / Income level§ (CNY/year) Low income (<30,000) 323 32.3% 20.0% 0.02 Low and middle income (30,000–60,000) 187 18.7% 25.0% Upper middle income (60,000–100,000) 240 24.0% 25.0% High income (>100,000) 250 25.0% 20.0% Note: ‘/’ means no available data.

* City population proportion was cited form the Beijing Yearly Statistic Book (2019).

† χ2 test.

§ Income was classified according to the Beijing Yearly Statistic Book (2019).Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample population and comparison to Beijing population proportion.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Comparisons of perceptions and behaviors between heatwave and non-heatwave periods in Beijing from June to July 2020. (A) Risk perception dominance; (B) Prevention behaviors.

Table 2 showed the logistic regression results of the individual perception of COVID-19 risks during heatwave and non-heatwave periods for both the overall and subgroup populations. Compared to non-heatwave periods, the OR of the total population increasing perceived concern and severity of heatwaves were 1.93 (95% CI: 1.64–2.27) and 1.86 (95% CI: 1.59–2.18), respectively, and those of COVID-19 were 1.64 (95% CI: 1.38–1.94) and 1.63 (95% CI: 1.39–1.92), respectively. The OR of “continuously doing” for mask wearing [0.42 (95% CI: 0.35–0.50)] and for taking well-ventilating public transportation [0.59 (95% CI: 0.44–0.79)] were all below 1, indicating that the possibilities of maintaining prevention behaviors declined during exposure to heatwaves. Subgroup analysis by gender, education level, income level, and occupation showed similar trends. In addition, the self-employed group [OR: 1.26 (95% CI: 0.33–4.80)] and face-to-face service staff [OR: 0.36 (95% CI: 0.14–0.91)] had lower likelihoods of wearing face masks less during heatwaves compared to other occupational groups.

Item COVID-19 prevention behaviors Heat perception COVID-19 perception Continuously wearing Never wearing Continuously ventilating Never ventilating Perceived concern Perceived severity Perceived concern Perceived severity Total population 0.42

(0.35, 0.50)2.11

(1.34, 3.33)0.59

(0.44, 0.79)1.63

(1.25, 2.13)1.93

(1.64, 2.27)1.86

(1.59, 2.18)1.64

(1.38, 1.94)1.63

(1.39, 1.92)Gender Men 0.33

(0.25, 0.43)5.73 (2.76, 11.91) 0.45

(0.29, 0.71)1.59

(1.09, 2.32)1.70

(1.36, 2.14)1.76

(1.41, 2.21)1.47

(1.16, 1.88)1.60

(1.27, 2.01)Women 0.52

(0.40, 0.67)0.64

(0.31, 1.3)0.72

(0.48, 1.07)1.92

(1.27, 2.89)2.24

(1.78, 2.83)1.96

(1.56, 2.46)1.82

(1.43, 2.31)1.66

(1.32, 2.08)Education level Senior high school and below 0.12

(0.08, 0.18)1.17 (0.39, 3.54) 0.37

(0.19, 0.70)1.59

(0.98, 2.58)1.34

(0.99, 1.81)2.41

(1.76, 3.31)2.37

(1.70, 3.29)2.23

(1.63, 3.05)University and above 0.63

(0.51, 0.78)2.39 (1.44, 3.95) 0.66

(0.48, 0.92)1.81

(1.29, 2.55)2.27

(1.87, 2.75)1.71

(1.42, 2.06)1.43

(1.17, 1.74)1.47

(1.21, 1.77)Income level Low income 0.60

(0.43, 0.82)4.91

(1.39, 17.33)0.78

(0.5, 1.24)1.56

(0.96, 2.53)2.12

(1.59, 2.82)1.99

(1.50, 2.65)1.39

(1.04, 1.87)1.80

(1.36, 2.39)Low and middle income 0.44

(0.28, 0.69)2.46

(0.61, 9.87)0.59

(0.31, 1.10)2.33

(1.25, 4.32)1.76

(1.21, 2.56)2.40

(1.65, 3.49)1.90

(1.28, 2.83)1.72

(1.18, 2.5)Upper middle income 0.39

(0.27, 0.56)2.05

(0.69, 6.12)0.28

(0.14, 0.56)2.66

(1.51, 4.69)1.60

(1.15, 2.22)1.65

(1.19, 2.29)2.01

(1.41, 2.86)1.34

(0.96, 1.86)High income 0.25

(0.17, 0.37)1.66

(0.88, 3.12)0.65

(0.31, 1.35)0.95

(0.52, 1.77)2.43

(1.75, 3.38)1.64

(1.19, 2.25)1.56

(1.11, 2.20)1.72

(1.24, 2.39)Occupation Office worker 0.27

(0.21, 0.35)6.41

(2.8, 14.64)0.47

(0.31, 0.71)1.56

(1.09, 2.22)1.68

(1.34, 2.10)1.77

(1.42, 2.22)1.72

(1.36, 2.19)1.80

(1.43, 2.26)Face to face service staffs 0.62

(0.40, 0.97)1.26

(0.33, 4.80)0.78

(0.40, 1.50)1.51

(0.73, 3.14)2.33

(1.57, 3.46)1.66

(1.13, 2.46)2.63

(1.72, 4.02)1.93

(1.30, 2.86)Self-employed 0.91

(0.60, 1.39)0.36

(0.14, 0.91)0.6

(0.29, 1.25)4.35

(1.79, 10.59)2.75

(1.89, 4.01)2.68

(1.85, 3.87)0.85

(0.58, 1.23)1.19

(0.83, 1.70)Other 0.37

(0.21, 0.64)8.85

(1.08, 72.72)0.88

(0.37, 2.12)1.76

(0.69, 4.49)1.78

(1.12, 2.84)1.57

(0.99, 2.48)2.19

(1.33, 3.60)1.53

(0.96, 2.44)Table 2. Odds ratios for different choices of COVID-19 prevention behaviors and risk perceptions compared heatwave to non-heatwave periods in subgroup population [OR (95%CI)].

HTML

-

This study provided quantitative evidence on how people in Beijing Municipality responded to compound heatwaves in the COVID-19 pandemic. We found both the perception of COVID-19 risk and 2 types of prevention behaviors of the studied sample were weakened during the heatwave period. The results of this study may be referenced by public health organizations to become better prepared for coping with the challenges brought by the COVID-19 pandemic and compound heatwave events.

Heatwaves may play a significant driving factor in reducing compliance to COVID-19 prevention measures. Uncomfortable physical and psychological feelings produced by shortness of breath, sultry, and sweating during heatwaves may be the primary reason for reduction in mask-wearing compliance. Furthermore, increased exposure to heat could steer public risk perception, understanding, and awareness of seeking a guide to prevent heat-related risk (9), resulting in heat-related risks dominating public perception during heatwave periods and reducing attention paid to COVID-19. In addition, misconceptions that the pandemic would decline during hot weather may have also adversely shaped risk perceptions on COVID-19 and weakened prevention (10). This poses an urgent challenge to public health authorities: how should we correctly guide the general population to take safe cooling action during the COVID-19 pandemic? The compounded effects of extreme weather during a global pandemic should be addressed as a critical urgency.

The likelihood of keeping wearing masks or taking well-ventilated public transportation decreased by different levels in most of the subgroups, especially mask-wearing behaviors. Self-employed and face-to-face service staff had relatively lower likelihood of decline in “continuously wearing masks,” reflecting China’s strict regulation on service staff, especially those who could not avoid close contact to the public (e.g., supermarket cashier, courier, salesperson, etc.) in the COVID-19 prevention guide. However, office workers were likely to become high-risk groups because they relaxed COVID-19 behaviors and showed higher possibility of reducing prevention behaviors. As personal norms are key to taking preventative action (11), better adaptation to heatwaves during the COVID-19 pandemic and targeted strategies are needed to maintain the awareness of various population subgroups.

Public health prevention strategies should address two major aspects of the problem. To fight against COVID-19, information publicity and health-risk education for COVID-19 should be maintained to promote public awareness for disease prevention efforts. In addition, strict disease control regulation in public venues (public transportation, supermarket, etc.) and work places (office rooms, schools, etc.) should be strengthened by the responsible administrations. To better adapt to extreme weather conditions, action guidelines should be critically considered by public health authorities to guide people to safely adapt to climate anomalies during the pandemic. This study suggests strengthening education, increasing public understanding of compounded risks, and coordinating different sectors to integrate public health, environment, and social organizations to resist compounded risks due to climate change, such as integrating messages on the spread of COVID-19 risks during weather forecasts.

This study was subject to several limitations. First, this was a retrospective survey and may have been subject to recall bias. However, the survey was conducted immediately after the Xinfadi COVID-19 outbreak and was designed to accurately capture individual memories of perceptions and behaviors during the entire period. Second, this was a web-based survey in which sampling may focus on people who were web users. But according to the latest Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development, as of June 2020, the number of web users exceeded 940 million and internet penetration rate reached 67% in China. Therefore, a web-based online survey could better adapt to people’s daily lifestyle and cover population characteristics of the city, especially in Beijing. Third, only two prevention behaviors were included. Other actions (such as avoid gatherings, maintain hand hygiene, etc.) should be further studied. Fourth, individual perception on heatwave or COVID-19 may have been influenced if they recently experienced heat-related diseases or respiratory diseases, thus there may be some bias since we did not investigate individual health information. Finally, this study included 1,000 participants, which were likely not fully representative of Beijing residents. Although the structure of the sample was partially consistent with the city population, attention should be paid when interpreting the results.

In conclusion, the worldwide collision of heatwaves and COVID-19 is an emerging global health challenge. This study could aid in understanding and adapting to the compounded risk for future disease control and prevention strategies.

Conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interests.

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: