-

Introduction: Nipah virus (NiV) infection is a highly fatal zoonosis lacking specific vaccines or treatments, posing a persistent threat to global health security; its re-emergence in India in early 2026 has further amplified these concerns. However, the risk of NiV importation into China remains unclear.

Methods: This study employed an integrated risk matrix and Borda count method, driven by multisectoral data including epidemiological parameters, civil aviation capacity, customs import trade, and geographical proximity. Importation risk was evaluated across two dimensions: likelihood and consequences. The Borda count method was subsequently utilized to rank the comprehensive risks among identified affected countries.

Results: Importation risk from five countries reporting NiV outbreaks between 1999 and 2026 was evaluated by scoring and ranking both likelihood and consequences. India and Bangladesh presented moderate importation risk to China, achieving the highest Borda points among South and Southeast Asian nations. Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore demonstrated low importation risk.

Conclusions: Countries with documented NiV outbreaks represent potential sources of importation to China, where stochastic viral entry poses a persistent threat in an increasingly interconnected world. Continuous multi-source surveillance coupled with dynamic risk modeling is therefore essential for safeguarding national biosecurity.

-

Nipah virus (NiV) infection represents a highly fatal zoonotic disease that poses a severe threat to global health security. As a World Health Organization (WHO) Research and Development Blueprint priority pathogen, NiV is characterized by an exceptionally high case fatality rate (40%–75%) and frequent spillover events from animal reservoirs to human populations (1–2). The extensive global air travel network creates substantial risk for NiV to spread beyond its endemic regions in South and Southeast Asia (3). Consequently, quantifying the risk of NiV importation is essential for strengthening national biosecurity frameworks and enhancing early warning capabilities.

As of early 2026, over 700 laboratory-confirmed human cases of NiV have been documented globally, with India emerging as a critical epicenter of recurrent outbreaks (4). While initial clusters were primarily localized in Malaysia, Singapore, India, and Bangladesh, genomic and serological surveillance has since identified NiV or NiV-like henipaviruses in approximately 20 countries across the Indo-Pacific and Africa (2,5). This geographical expansion closely aligns with the ecological niche of its natural reservoir, fruit bats of the genus Pteropus (6). Notably, recent outbreaks in South Asia have signaled a concerning shift toward more efficient human-to-human transmission, with secondary attack rates frequently reaching epidemic thresholds (3). The intensification of trade and migration between China and these ecologically high-risk zones under the Belt and Road Initiative has significantly elevated the probability of pathogen introduction. This evolving landscape necessitates a high-resolution, spatiotemporal evaluation of NiV importation risks.

Given the rapid spread of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) in an increasingly interconnected world, the ability to prioritize interventions is critical, particularly when resources and time are constrained. Risk assessment provides a fundamental framework for identifying high-risk areas and characterizing key transmission factors (7–8). By offering a structured approach to quantify threats, it enables timely and strategic interventions to mitigate the introduction and spread of high-consequence pathogens. Conventional risk assessment methods — ranging from expert-led approaches such as the Delphi technique to complex statistical models — often face a dual challenge: expert-led methods are susceptible to subjective bias, while statistical models are frequently constrained by stringent data requirements and limited data availability (7–8).

To address these methodological limitations, this study adopts an integrated approach that combines qualitative and quantitative evaluation frameworks. The risk matrix method establishes a robust semi-quantitative structure for categorizing risks according to their likelihood and potential consequences, while the Borda count method provides precise, quantitative ranking of these identified threats. This data-driven integration minimizes subjective weighting bias and enhances discriminatory power, thereby enabling the prioritization of countries even when they fall within identical risk categories. Although this hybrid framework has demonstrated utility in assessing other EIDs — including Ebola, Mpox, and Lassa fever — the specific importation risk of NiV into China remains inadequately characterized. Consequently, this study employs this integrated model to systematically evaluate and rank the risks posed by key NiV-affected countries, with the objective of providing an evidence-based reference for China’s early warning systems and strategic preparedness initiatives.

In this study, we categorized and ranked the NiV importation risk across two dimensions — likelihood and consequences — by synthesizing multi-source data including epidemiological profiles, aviation capacity, animal product trade, and geographical proximity.

Epidemiological data — including human NiV cases, deaths, and case fatality rates from five countries (Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore) between 1999 and 2026 — were obtained from the WHO Disease Outbreak News, official government websites, and peer-reviewed literature (4,9–10). Risk assessment indicators were synthesized from multiple sources: basic reproductive numbers (R0) were derived from the WHO and literature; aviation capacity from the Official Aviation Guide (11); trade statistics for animals and animal products from the General Administration of Customs of China (GACC) (12); and terrestrial border information from geospatial datasets (Table 1).

Country Cumulative cases Cumulative deaths Case fatality rate (%) R0 Monthly inbound aviation capacity (thousand)*† Trade in animals and animal products (million CNY) † Terrestrial proximity to China The time lag between the latest outbreak of Nipah Virus infection and 2026 by country (years) Bangladesh 348 250 71.84 0.33–0.48 36 56.93 Non-bordering but proximal 0 India 106 74 69.81 ~0.33 26 1,252.20 Bordering with natural barriers 0 Malaysia 265 105 39.62 ~0 290 1,202.01 Non-adjacent and ocean-isolated 27 Philippines 17 9 52.94 ~0 135 163.88 Non-adjacent and ocean-isolated 12 Singapore 11 1 9.09 <0.1 375 34.95 Non-adjacent and ocean-isolated 27 Note: ~ means around.

Abbreviation: CNY=Chinese Yuan; R0=basic reproductive number.

* data represent total monthly seats capacity for inbound routes to China;

† monthly data; cumulative cases and cumulative case fatality rate (%) of Nipah virus infection were from the year of 1999–2026.Table 1. Epidemiological profiles and risk assessment indicators for key Nipah virus-affected countries (1999–2026).

This study employed a risk matrix to evaluate NiV importation risk into China across two primary dimensions — likelihood and consequences — following WHO Rapid Risk Assessment guidelines (Table 2). Through comprehensive literature review, we identified key indicators for each dimension. Likelihood was assessed using five indicators: cumulative case count, monthly inbound aviation capacity, import value of animals and animal products, terrestrial proximity to China, and outbreak recency (defined as the time interval between the most recent outbreak and 2026). Consequences were determined by two epidemiological parameters: R0 and cumulative case fatality rate. Risk assessment indicator scores were established through a three-step process. First, we reviewed existing literature on infectious disease importation risk (7). Second, we synthesized the epidemiological characteristics of NiV alongside cross-border movement patterns of personnel and cargo between China and the five key countries. Third, we conducted expert consultations to refine the scoring framework. Public health professionals performed the assessment in strict adherence to WHO guidelines (13). Classification and scoring criteria were derived from systematic review of multi-source surveillance data to ensure both objectivity and reproducibility. Detailed scoring criteria are presented in Table 3.

Likelihood Consequences Minimal Minor Moderate Major Severe Almost certain L M H VH VH Highly likely L M H VH VH Likely L M H H VH Unlikely L L M H H Very unlikely L L M H H Note: Actions and response framework (based on WHO guidelines): L (Low risk): Managed according to standard response protocols, routine control programmes, and regulation (e.g., monitoring through routine surveillance systems). M (Moderate risk): Roles and responsibilities for the response must be specified; specific monitoring or control measures are required (e.g., enhanced surveillance). H (High risk): Senior management attention is needed; there may be a need to establish command and control structures; a range of additional control measures will be required, some of which may have significant consequences. VH (Very high risk): Immediate response is required even if the event is reported out of normal working hours; immediate senior management attention is needed (e.g., establishing command structures within hours); the implementation of control measures with serious consequences is highly likely. Table 2. Risk matrix.

Assessment indicators Factors Classification Risk score Importation likelihood Cumulative cases ≤49 2 50–499 4 500–999 6 1,000–4,999 8 ≥5,000 10 Monthly inbound aviation capacity (seats)*† ≤49 2 50–299 4 300–799 6 800–1,499 8 ≥1,500 10 Monthly importation value of animals and animal products (Million CNY)† ≤49 2 50–499 4 500–1,999 6 2,000–4,999 8 ≥5,000 10 Terrestrial proximity to China Non-adjacent and ocean-isolated 2 Non-bordering but proximal 4 Bordering with natural barriers 6 Bordering with land ports of entry 8 Bordering with extensive, porous boundaries 10 The time lag between the latest outbreak of Nipah virus infection and 2026 by country (years) ≤1 10 2–3 8 4–5 6 6–9 4 ≥10 2 Importation consequences R0 ≤0.5 2 0.6–0.9 4 1–1.4 6 1.5–2.4 8 ≥2.5 10 Cumulative case fatality rate (%) ≤9 2 10–39 4 40–59 6 60–79 8 ≥80 10 Abbreviation: CNY=Chinese Yuan; R0=basic reproductive number.

* data represent total monthly seats capacity for inbound routes to China;

† monthly data; cumulative cases and cumulative case fatality rate (%) of Nipah virus infection were from the year of 1999–2026.Table 3. Risk assessment indicators of importation likelihood, consequences, and corresponding scores.

The indicator weighting scheme was established based on the epidemiological hierarchy of transmission, assigning the highest priority to the source of infection and primary transmission routes. To align with the WHO risk matrix framework, the Equal Interval Method was employed to stratify the normalized theoretical scores (0–10) linearly into 5 distinct risk levels. (13) The formulas for importation likelihood and consequences of NiV are as follows. First, the importation likelihood score was calculated as: the score of the number of cumulative cases × 40% + the score of monthly inbound aviation capacity × 30% + the score of monthly importation value of animals and animal products × 10% + the score of terrestrial proximity to China × 10% + the score of the time from the last outbreak to 2026 × 10%. This study then derived the importation likelihood risk score using 5 levels: very unlikely (0–2 points); unlikely (3–4 points); likely (5–6 points); highly likely (7–8 points); and almost certain (9–10 points). The time lag in years between the latest outbreak of NiV and 2026 was calculated by country as 2026 minus the outbreak year. Second, the importation consequences score was calculated as R0 score plus the cumulative case fatality rate score. Cumulative cases were equal to the total number of cases in countries with NiV from 1999–2026. Cumulative case fatality rates =

$ \dfrac{{{cumulative\; deaths\; from\; 1999\; to\; 2026}}}{{{cumulative\; cases\; from\; 1999\; to\; 2026}}}\times100\% $ This study classified the final importation consequences risk score into 5 levels: minimal (0–2 points); minor (3–4 points); moderate (5–6 points); major (7–8 points); and severe (9–10 points). Third, according to the importation likelihood and consequences levels in the risk matrix (Table 2), the importation risk of NiV into China was divided into 4 levels (low, moderate, high, and very high), which corresponded to green, yellow, orange, and red zones, respectively. Finally, this study used the Borda count method to rank the NiV importation risk (7).This study used the Borda count method to rank NiV importation risks. First, the Borda points for each importation risk were calculated as the sum of the rank of its importation likelihood and the rank of its consequences risk level (7). This study then sorted the Borda points from largest to smallest and assigned corresponding counts of 0, 1, …, N-1. A lower Borda count indicates a greater likelihood of NiV importation to China and potentially more severe consequences. Borda points were calculated using the following formula:

$$ {b_i} = \sum\limits_{k = 1}^m {\left( {N - {r_{ik}}} \right)} $$ Where N equals the total number of at-risk countries, this study defined at-risk countries as those with NiV importation risk. Therefore, this study set N as 5. The variable m equals the 2 dimensions of risk assessment. rik equals the number of countries posing a higher risk than the risk for indicator i under criterion k, and bi equals the Borda points of assessment indicator i.

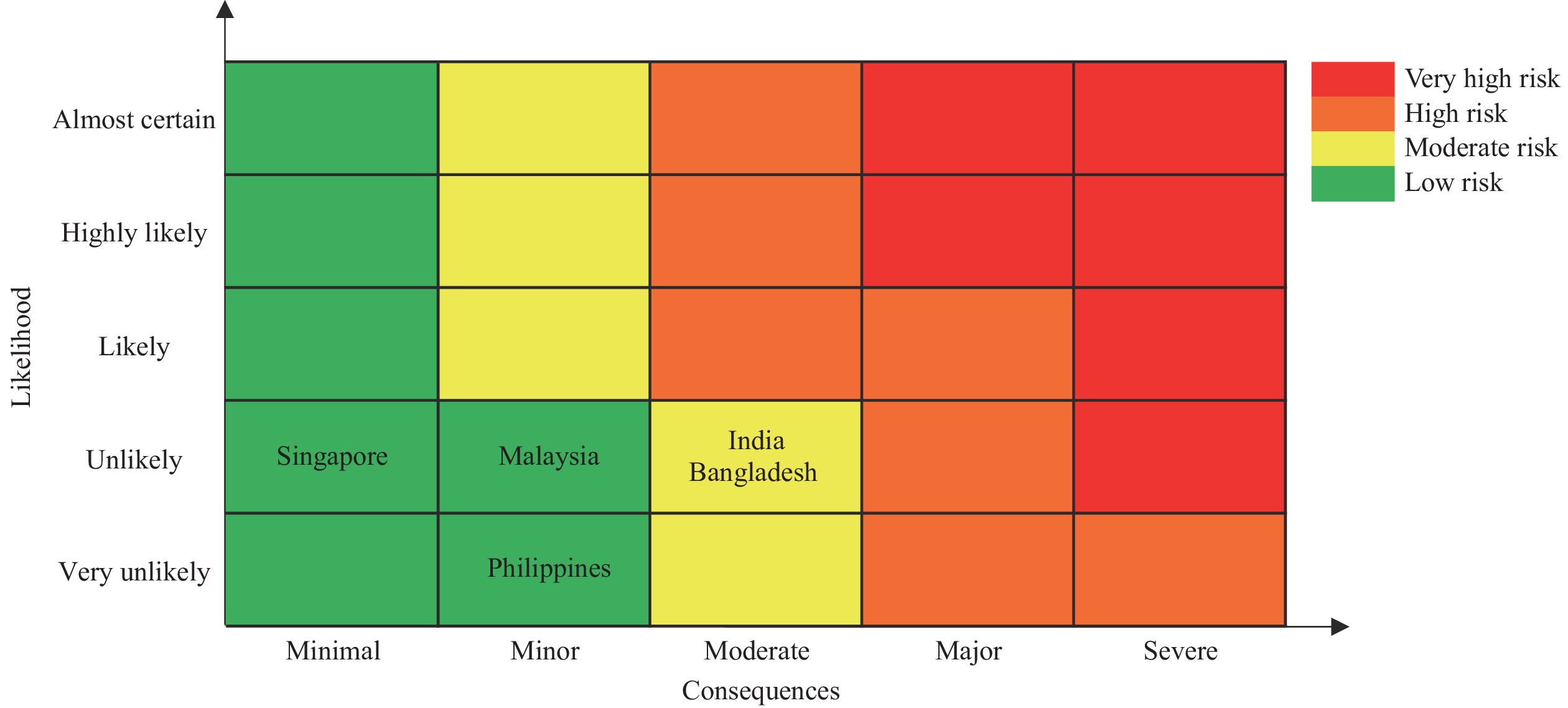

This study scored and ranked the risk of NiV importation for 5 countries that experienced outbreaks from 1999 to 2026. It considered global importation likelihood and consequences to derive overall importation risks (Table 4). Using a risk matrix diagram, this study then visualized these total risks, with red, orange, yellow, and green representing very high, high, moderate, and low importation risk, respectively (Figure 1). Its integrated application of the risk matrix and Borda count method demonstrated that China faces a risk of NiV importation. Regarding importation likelihood, India presented the highest risk (score=4.4), while the Philippines presented the lowest (score=2.8). Concerning importation consequences, India and Bangladesh exhibited the highest risk (score=5), whereas Singapore had the lowest (score=2) (Table 4). India and Bangladesh posed a moderate NiV importation risk (Figure 1) due to the highest Borda points of 10 and ranking first. Malaysia, Singapore, and the Philippines presented low importation risks (Figure 1). The Philippines exhibited the lowest Borda points of 4 and ranked fifth (Table 4).

Country name Importation likelihood score Importation consequences score Risk levels Borda points Borda count Risk sequence of importation India 4.4 5 M 10 0 1 Bangladesh 4.0 5 M 10 0 1 Malaysia 3.8 3 L 8 2 3 Singapore 3.2 2 L 6 3 4 Philippines 2.8 4 L 4 4 5 Abbreviation: L=low risk; M=moderate risk. Table 4. Importation risks from countries with Nipah virus infection outbreaks to China from 1999–2026.

-

This study employs an integrated risk matrix and Borda count approach to quantify the risk of NiV importation into China. By combining structured professional assessment with multi-sectoral indicators — specifically civil aviation and animal trade data — this framework enhances the granularity of risk exposure assessment from personnel mobility and potential fomite transmission. Unlike models that rely exclusively on reported health data, this multi-dimensional analysis offers a practical tool for identifying high-risk monitoring nodes in data-limited scenarios. These rankings provide a reproducible reference for prioritizing high-risk importation sources, thereby enabling more targeted resource allocation and strategic containment measures.

This study determined that India and Bangladesh pose a moderate risk of NiV importation to China, characterized by high consequences despite an “unlikely” likelihood of immediate large-scale introduction. This elevated risk is primarily driven by the dominance of the NiV-Bangladesh/India lineage (NiV-B). Compared to the Malaysian genotype (NiV-M), NiV-B demonstrates human-to-human transmissibility and exhibits a significantly higher case fatality rate (40%–75%) (14–15). Furthermore, phylogenetic analyses indicate that NiV-B possesses substantial evolutionary potential, raising concerns about its capacity to evolve enhanced transmissibility traits (15). This risk stems from a convergence of critical factors: high lethality, respiratory symptoms that facilitate human-to-human transmission, and frequent spillover events in densely populated regions (1,15). Collectively, these elements underscore a persistent and evolving threat to regional biosecurity. Notably, while the genetic lineages of NiV (e.g., NiV-B and NiV-M) differentially influence human-to-human transmissibility and virulence, they were not treated as standalone variables in the risk matrix to avoid multicollinearity. Instead, the epidemiological impacts of distinct lineages were inherently quantified through the case fatality rate and R0 indicators within the consequences dimension. Consequently, countries predominantly affected by the highly virulent NiV-B lineage received higher consequence scores, ensuring that the biological threat of the specific viral strain was objectively integrated into the final risk ranking.

Transmission of NiV-B is markedly amplified in confined settings, particularly healthcare facilities. The 2018 Kerala outbreak demonstrated that index cases with persistent respiratory distress triggered superspreading events, infecting over 10 contacts through droplet transmission — a pattern that typically intensifies during the terminal phase of infection (16). The January 2026 outbreak in West Bengal exhibited a similar nosocomial transmission pattern within Kolkata (3). These recurring events underscore the persistent risk of viral amplification in healthcare settings, especially in dense urban environments where the virus can exploit high population density to facilitate broader community spread.

Beyond the immediate threat of nosocomial amplification, the endemic persistence of NiV in South Asia stems from a specific socio-ecological nexus that drives marked seasonality from December through May. This epidemic window coincides precisely with the traditional harvesting season for raw date palm sap (1,14–15). Overnight exposure of open collection containers attracts foraging by Pteropus medius fruit bats, the natural reservoir, resulting in sap contamination through infected saliva or excreta. This unique spillover pathway enables the virus to breach species barriers and seed recurrent human infections (15). Although local surveillance capacity has improved, the underlying threat of cross-border transmission persists, driven by extreme population density and the clinical difficulty of differentiating NiV from other endemic febrile illnesses in the region.

The confirmed NiV case in the Rajshahi Division of Bangladesh in early February 2026 provides empirical validation of the risk factors identified in this study (17). The case occurred during the characteristic low-temperature, dry-winter transmission window and within the high-risk “Nipah Belt,” where human settlements overlap with fruit bat habitats — consistent with the temporal and spatial risk patterns identified in our analysis. The fatal outcome following exposure through raw date palm sap consumption in a high-density rural setting further aligns with the behavioral and demographic drivers we highlighted. The rapid clinical progression and 100% case fatality rate underscore both the high virulence and predominantly sporadic transmission dynamics of NiV. While such extreme virulence may constrain sustained human-to-human transmission and reduce the probability of frequent cross-border spread through large-scale outbreaks, it indicates that even a single imported case could present a substantial public health challenge. This low-frequency, high-consequence risk profile justifies the designation of Bangladesh as a moderate, rather than low, importation risk for China.

Furthermore, the public health capacities of endemic countries substantially influence the magnitude of NiV outbreaks and the level of transnational transmission risk. Although India features relatively robust rapid response and diagnostic networks, delayed early clinical recognition frequently triggers severe nosocomial amplification (3,16). Conversely, in Bangladesh, spillover events are mainly dispersed across remote rural areas, where surveillance blind spots and inadequate differential diagnostic capability often result in unnoticed early community transmission (4,17). Collectively, these systemic vulnerabilities may create a critical time window for the unmonitored dissemination of the pathogen. Consequently, despite overall improvements in local epidemic containment, such public health gaps sustain the baseline probability of stochastic exportation by individuals in the incubation period. These factors further underscore the necessity for China to maintain continuous border surveillance, quarantine measures, and risk assessments.

Despite these combined biological threats and systemic public health vulnerabilities, the likelihood of importation into China remains Unlikely. The Himalayan massif functions as a formidable natural buffer, while the current volume of direct aviation flux between the affected South Asian regions and Chinese ports of entry remains relatively low. Crucially, this residual risk is effectively mitigated by China’s proactive biosecurity framework. In 2021, the China CDC issued technical guidelines that established standardized molecular assays and provided a framework for the stockpiling of emergency diagnostic kits. This was followed in 2024 by the designation of NiV as a priority target for frontier health and quarantine (18–19). Recently, during the January 2026 outbreak, the GACC and China CDC have initiated intensified measures, including mandatory border screenings, the decentralization of laboratory identification to provincial centers, and the clinical evaluation of domestic antiviral candidates (20). These measures establish a robust defensive shield against stochastic importation. However, in a globalized context, the potential for stochastic entry via highly mobile populations remains a persistent threat.

The quantitative results may provide a reference for optimizing control strategies for customs and public health authorities. For travelers from moderate-risk regions, targeted surveillance combining symptom screening with travel history verification is advised, particularly during the NiV infection outbreak season (Winter/Spring). Simultaneously, risk-based inspection should prioritize high-risk vectors, such as fresh fruits in commercial trade and unregulated biological products, to intercept potential viral importation. Furthermore, given NiV’s exceptional lethality, strengthened preparedness — including enhanced diagnostic and clinical response capacity — is essential to mitigate low-likelihood, high-consequence risks.

This study has several limitations that warrant caution when interpreting the results. First, this assessment was conducted as a rapid risk assessment and therefore did not include a multi-expert elicitation process (e.g., Delphi panels). Although scoring was guided by predefined evidence-based criteria and WHO Rapid Risk Assessment guidance, some uncertainty may remain in cut-off selection and weighting. Second, as an ordinal measure, the Borda count captures the relative positioning of risks but does not quantify the absolute magnitude of differences between specific rankings. Third, the risk matrix does not explicitly incorporate dynamic biological data of Pteropus bats, including population density, migratory patterns, or seasonal viral shedding, which may affect spillover dynamics. In addition, while the broad seasonality of NiV outbreaks is captured, the model does not fully parameterize the influence of climatic fluctuations on host spatial distribution, potentially overlooking localized high-risk areas. Fourth, the assessment focused on countries with historically confirmed human cases, which may omit potential de novo introductions from other regions within the reservoir range. Lastly, differences in surveillance sensitivity and diagnostic capacity across countries could lead to underestimation of risk, particularly in resource-limited settings. Despite these limitations, prioritizing established endemic zones remains a pragmatic strategy for current resource allocation. Future frameworks should integrate multi-source ecological niche modeling and health-system data to enhance the precision of risk assessments.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: