-

Introduction: In late August 2025, a locally transmitted CHIKF outbreak was detected in Licheng District, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province. On September 3, 2025, two locally acquired cases without travel history to Licheng District were reported in the adjacent Nan’an City, Quanzhou City. This study aimed to identify the infection source of the local chikungunya cases in Nan’an City.

Methods: Field epidemiological investigations were conducted to collect case-related information and trace the infection source. Aedes mosquito density was monitored in the core epidemic area. Whole-genome amplification and sequencing were performed on chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in the serum samples of the cases. The obtained sequences were aligned with those from GenBank, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed for viral genotypic analysis.

Results: Nine days before the onset of the two local cases, an imported chikungunya case from Licheng District had received treatment at Clinic E near their residential area. Whole-genome sequencing revealed complete identity among the CHIKV strains from the two local cases and the one imported case, all belonging to the ECSA genotype.

Conclusion: Epidemiological link between the locally acquired CHIKF cases in Nan’an City, Quanzhou and the imported case from Licheng District, Quanzhou. In a previously CHIKV-free non-endemic area with Aedes mosquitoes, secondary local cases may emerge approximately 9 days after the introduction of imported viremic cases.

-

CHIKF is an acute mosquito-borne infectious disease caused by CHIKV, characterized by fever, rash, and severe arthralgia (1). Global climate change, increased international travel and trade, have expanded it from tropical/subtropical to temperate zones,posing a persistent global public health threat (2). In southern China, widespread Aedes albopictus has facilitated imported cases and subsequent local transmission (3–5).

The urban CHIKV transmission cycle involves three key epidemiological links: viremic human hosts, infected mosquito vectors (with a typically 2–10 days EIP), and susceptible individuals (with a typically 1–12 days IIP) (6). While laboratory studies have defined EIP and IIP ranges, empirical field data on the complete transmission cycle (EIP+IIP) during real-world remain scarce. Such data are critical for establishing evidence-based timeframes to guide grassroots public health interventions.

In late August 2025, a locally transmitted CHIKV outbreak was reported in Licheng District, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province. On September 3, two locally acquired cases involving siblings were identified in the adjacent Nan’an City, Quanzhou City. Notably, neither case reported travel to Licheng District or other CHIKV-endemic areas within the 12 days preceding symptom onset. This study aimed to identify the infection source of the local chikungunya cases in Nan’an City, and provide empirical evidence to inform prevention and control strategies against importation-driven local transmission in non-endemic regions.

The Nan’an CDC collected four datasets: 1) clinical manifestations and laboratory results of the two index cases and their co-exposed individuals; 2) detailed activity trajectories and exposure histories during the 12 days preceding symptom onset; 3) entomological surveillance data (Breteau Index measurements for Aedes larvae and Adult Biting Index assessments for adult mosquito density) within the 100-meter radius around Clinic E and the patients’ residences; and 4) epidemiological linkage data to trace potential infection sources.

Viral nucleic acids were extracted using a magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction kit (ZYHJ, 2507003) and an automated extraction system (EXM 3000). Serum samples underwent CHIKV nucleic acid testing with a triple detection kit for dengue virus, Zika virus, and chikungunya virus using fluorescent PCR on a real-time quantitative PCR system (QuantStudio 7 Flex), in accordance with the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for CHIKV (2025 Edition).

Viral RNA was extracted from patient serum samples and reverse transcription followed by whole-genome targeted amplification of CHIKV was performed using the BK-CHIKV024 kit (Hangzhou Baiyi). Library construction was conducted using a no-amplification barcoding kit , and pathogen genome sequencing was conducted on a GridION X5 nanopore sequencing platform. Baiyi Analysis Software (version 5.2, Hangzhou Baiyi Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China), was used to assess sequencing data quality and assemble the CHIKV whole genome with GCF_002889555.1 as the reference sequence. Sequences obtained from this study (Cases 1 and 2) were aligned with sequences from the suspected linked case, the first case strain from Licheng District, and representative CHIKV genotype sequences retrieved from the GenBank database. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT software (version 7.487, Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tokyo, Japan) and the best-fit nucleotide substitution model (GTR+F+I) was determined with IQ-TREE (version 2.4.0, Bui Quang Minh, Department of Evolutionary Biology of Vienna, Vienna, Austria). A Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree was then constructed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

-

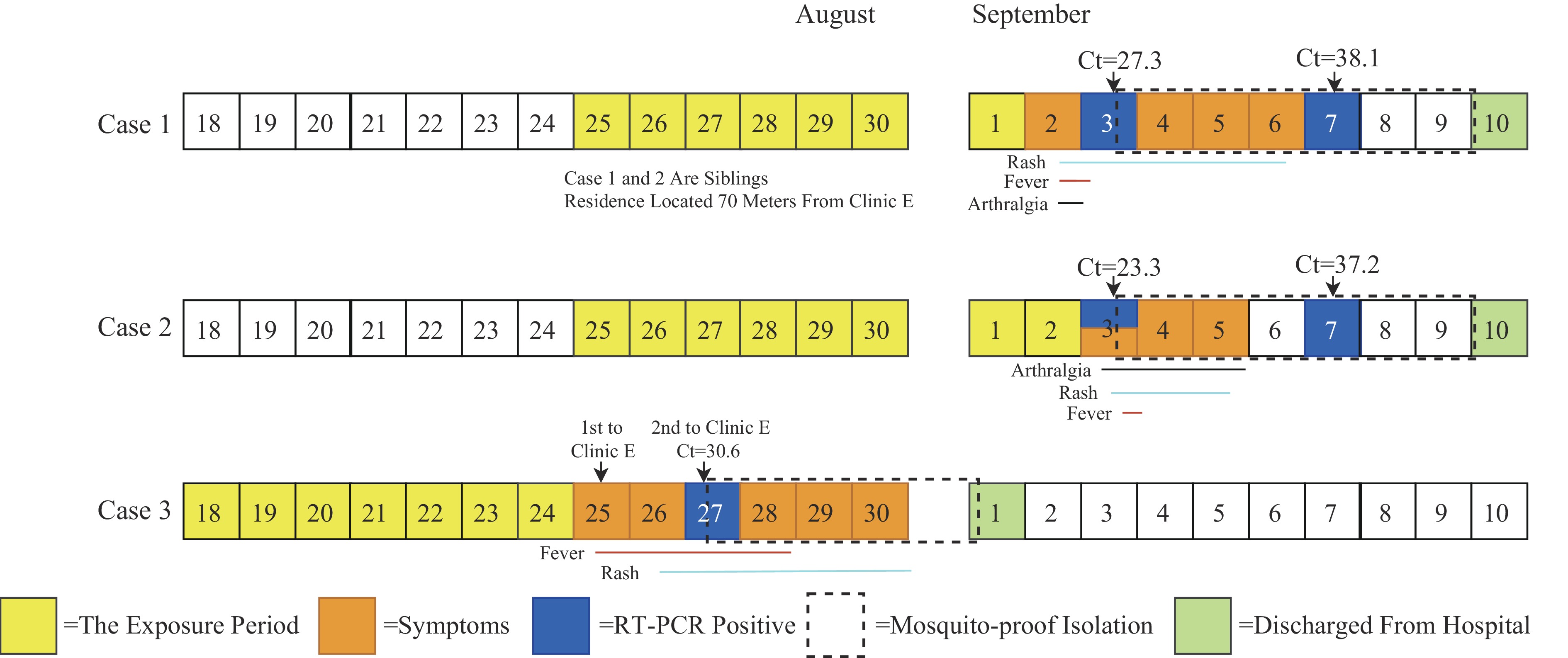

Case 1: A 10-year-old male primary school student developed red maculopapular rashes on both thighs with mild wrist joint pain on the afternoon of September 2, the rash subsequently spread systemically. He presented to D Community Health Center the same day with a temperature of 37.8 °C. Laboratory tests revealed negative dengue virus NS1 antigen. He revisited D Community Health Center on September 3 with a temperature of 37.6 °C. A blood sample was sent to the Nan’an CDC laboratory for testing, with positive CHIKV nucleic acid (Ct=27.3).

Case 2: A 16-year-old female middle school student (elder sister of Case 1) developed ankle joint pain in September 3, followed by scattered red maculopapular rashes on her limbs, accompanied by wrist and finger joint pain. At 20∶00, her temperature was 38.0 °C. Following the of Case 1’s diagnosis, local health staff collected her blood sample for testing, with positive CHIKV nucleic acid (Ct=23.3).

Both cases had the typical clinical triad of CHIKV infection and were confirmed by RT-PCR, representing the first locally transmitted CHIKV cases reported in Nan’an City, Quanzhou. Neither case had traveled outside Nan’an City in the 12 days prior to symptom onset. Environmental investigations on September 3 showed that the Breteau Index of 11.3 and Adult Biting Index of 1.6 mosquitoes per person per hour within a 100-meter radius of Clinic E and the patients’ residences.

-

Three co-exposed individuals (parents and grandmother) were identified and evaluated. None exhibited clinical symptoms, and all tested negative for both CHIKV nucleic acid and antibodies.

Active case finding was conducted across all households (1,655 households, 3,993 individuals) within the core exposure areas (defined as a 100-meter radius surrounding Clinic E and the patients’ residences) and at Community Health Center D. A retrospective investigation covering the period from August 15 to September 3 was implemented using questionnaire surveys combined with symptom screening (fever, rash, arthralgia). This investigation identified 13 febrile cases and 2 cases presenting with rash. Serum samples from all identified cases tested negative for CHIKV nucleic acid.

Since August 20, Health Center D has implemented strict fever clinic protocols and triage systems while requiring village clinics within its jurisdiction to enhance screening for patients presenting with fever, rash, arthralgia, and relevant epidemiological history. Suspected cases were promptly referred for further evaluation. As of September 3, Health Center D had submitted specimens from 12 suspected cases to the Nan’an CDC for testing. With the exception of 3 cases, all results were negative.

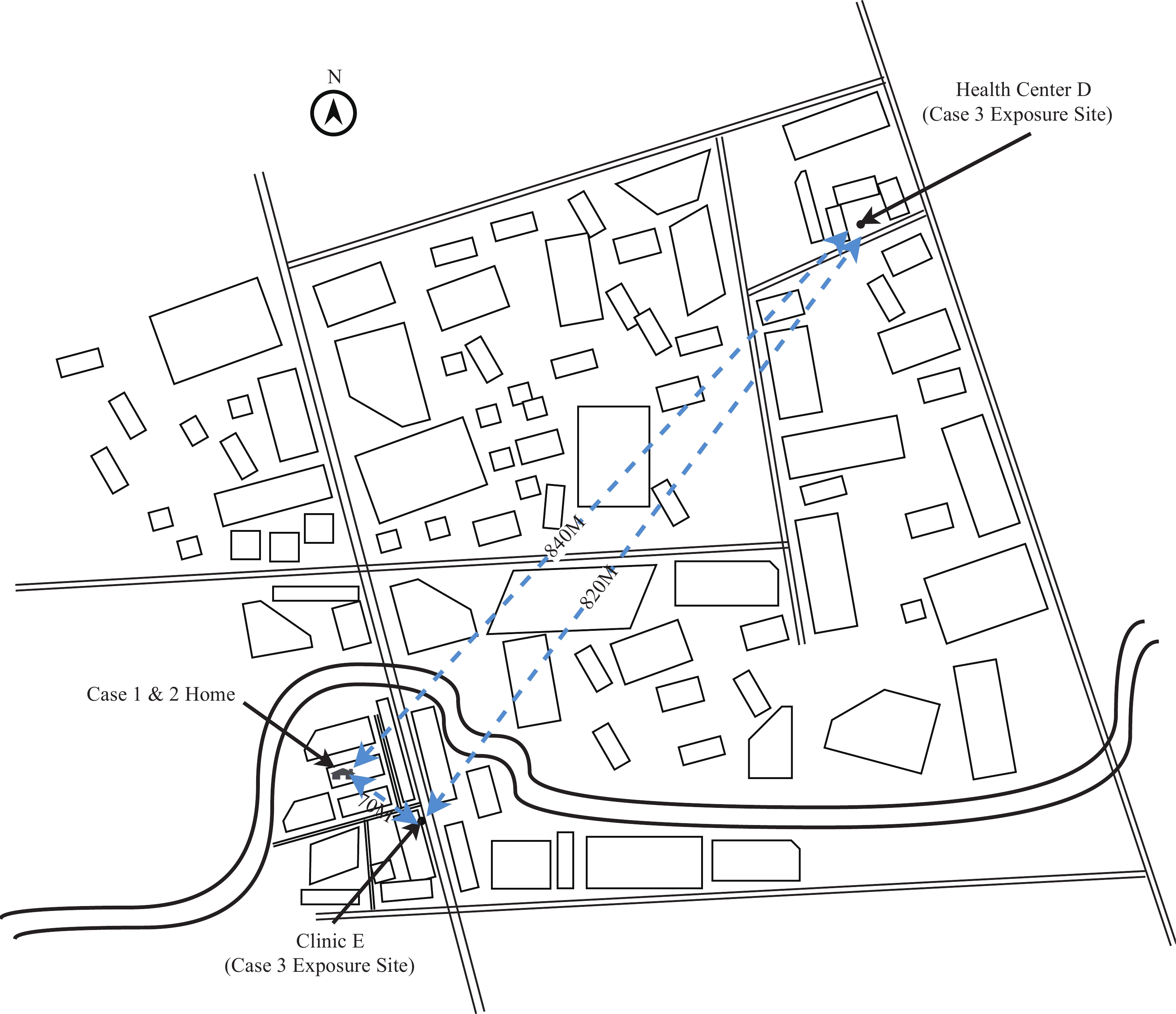

Activity trajectory mapping demonstrated that the sibling pair resided approximately 840 meters from Community Health Center D and only 70 meters from Clinic E (Figure 1). Further investigation revealed that on August 25, Clinic E had treated a patient from Licheng District (Case 3), who had onset of symptoms on August 25 and was laboratory-confirmed on August 27. The patient received intravenous infusion therapy at the clinic for 2 hours (15∶00–17∶00) without effective mosquito prevention measures. On August 27 at 8∶30, the patient returned to Clinic E for an additional 15 minutes. Case 3 resided in Licheng District, where he had acquired the infection, making him an associated case of the local transmission outbreak in that district. The straight-line distance between Case 3’s residence and the sibling pair’s residence was approximately 7 km, and approximately 6.8 km from Clinic E. Due to his travel history to Licheng District, the patient was immediately referred to the fever clinic of Community Health Center D. His CHIKV nucleic acid test returned positive (Ct=25.1), and the case was reported as an imported case linked to the Licheng District outbreak. The epidemiological relationships among the three cases are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Spatial relationship between residential locations of Cases 1 and 2 and exposure sites of the imported case.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.Clinical course and laboratory results of three chikungunya virus cases in Fujian Province, China, 2025.

Note: An amplification curve displaying a characteristic S-shape with a Ct value≤38 indicates a positive result; a Ct value >41 or no detection indicates a negative result. Suspected positive results exhibit a typical S-shaped amplification curve with 38<Ct value≤41, requiring retesting. If retest results are consistent, the sample is classified as positive; if the Ct value>41 or remains undetected, the sample is classified as negative.

Abbreviation: CHIKV=chikungunya virus; RT-PCR=real-time polymerase chain reaction; Ct=cycle threshold.

Case 3’s activity trajectory during the viremic period (August 25–31) was confirmed through medical records, transportation record (ride-hailing orders, walking trajectories), and interviews. He had visited only three locations: his residence in Licheng District, Clinic E, and Community Health Center D, with no other potential exposure sites identified. He visited Clinic E on August 25 and 27, remaining at home for the remainder of the period without going out and his trajectory was complete and verifiable.

-

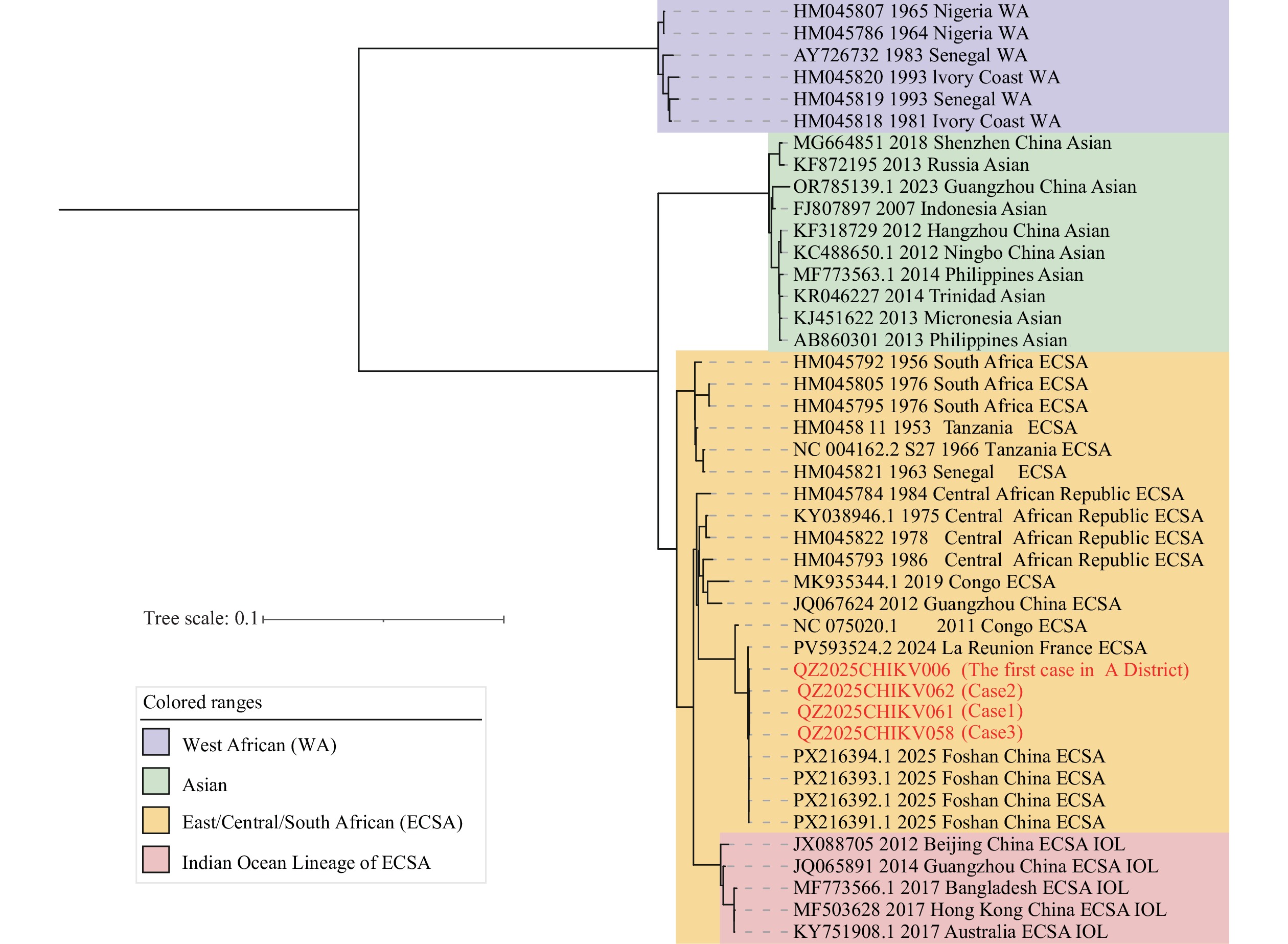

Whole-genome sequencing revealed complete identity among the CHIKV strains from all three cases, with 99.99% similarity to the first case strain from Licheng District. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that these three sequences clustered within the same branch as the first Licheng District case strain, the 2025 Foshan sequences (PX216391.1-PX216394.1), and the 2024 Réunion Island sequence (PV593524.2), all belonging to the East/Central/South African (ECSA) genotype. Furthermore, the sequences within this cluster exhibited complete identity and high homology in the E1 and E2 gene regions, forming a branch clearly distinct from other genotypes (Figure 3). This molecular evidence confirms a direct epidemiological link between the two locally acquired cases in Nan’an and the imported case from Licheng District.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.Phylogenetic tree of chikungunya virus strains based on Whole-Genome Sequences.

Note: Viral strain sequences downloaded from GenBank were aligned using MAFFT software. Purple denotes the WA lineage, green represents the Asian lineage, yellow indicates the ECSA lineage, and pink represents the Indian Ocean Lineage of the ECSA genotype.

Abbreviation: WA=West African; ECSA=East/Central/South African.

-

Upon outbreak identification, targeted measures were initiated per mosquito-borne disease guidelines (6-7): medical institutions enhanced surveillance to detect and report suspected cases; all confirmed cases received mosquito-proof isolated treatment to block transmission. Individual epidemiological investigations focused on 12-day pre-onset activity/travel history to clarify infection source (imported/local), with 12-day health monitoring for 3 exposed contacts. Three-tiered zones were delineated (core zone: 100-meter radius, warning zone: 200-meter extension from the core, monitoring zone: involved communities). Core zone completed household surveys, adult mosquito killing and breeding site cleaning in 3 days. Community education promoted “no stagnant water, no mosquitoes”, mobilizing residents to eliminate Aedes breeding sites (8). Emergency control terminated with 22 consecutive days of no secondary cases and standard core zone mosquito density (6). These measures effectively controlled spread and safeguarded public health.

-

This investigation confirmed that local CHIKV cases in Nan’an City, Quanzhou, were triggered by an imported case from the adjacent Licheng District, Quanzhou. Both epidemiological and molecular evidence established a clear transmission link among the three reported cases. As of September 3, Case 3 was the first and only imported CHIKV case reported in Nan’an City. Epidemiological investigation confirmed that he acquired the infection in Licheng District, a known outbreak area. Subsequently, the high genetic homology of the viral strains from Cases 1 and 2 (the first locally transmitted cases in Nan’an City) with the strain from Case 3 — particularly the 100% identity in the E1 and E2 genes — provided definitive molecular evidence for this transmission link. Furthermore, active case searching within the core exposure areas revealed no additional cases, further confirming that this outbreak was limited and focal in nature.

A key empirical finding was the 9-day interval from the initial exposure of the imported case (Case 3) at Clinic E to the onset of the first local secondary case. This timeline is consistent with the combined EIP and IIP for CHIKV. Recent research provides context for this finding; Wan et al. (9) demonstrated that the viremic period lasts from day 0 to day 7 after symptom onset, representing the phase of highest infectiousness. Considering the timeline and spatial characteristics of this study, Case 3 spent 2 hours at Clinic E on August 25 without effective mosquito prevention measures. This scenario represented the period of highest probability for mosquito bites and subsequent infection. Therefore, the approximately 9 days interval from this exposure to the onset of the first local case is epidemiologically plausible. If exposure had occurred during his shorter visit on August 27, the interval would have been approximately 7 days. This range of 7–9 days aligns with the theoretical sum of the incubation periods, with the 9-day interval being better supported by the context of longer unprotected exposure. Although the 9-day interval is not universally applicable, it provides a crucial “action benchmark” for rapid response in non-endemic areas. The absence of symptoms and negative laboratory test results among all co-exposed household members excluded the possibility that family members served as a source of transmission to Cases 1 and 2.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size (3 cases) means that the observed 9-day interval represents an empirical finding from a single outbreak rather than a universally applicable transmission cycle. The EIP depends heavily on environmental temperature (10) and Aedes density, while the IIP varies with individual immunity. Consequently, this interval cannot be generalized to other regions, seasons, or environmental conditions. Second, the exact date of mosquito infection remains uncertain, yielding an estimated range of 7–9 days. Third, the absence of CHIKV-positive mosquito samples from the core exposure area means direct vector evidence is lacking. However, this finding aligns with the characteristically low detection rates observed in small-scale outbreaks. it is likely attributable to low viral infection rates and inherent sampling limitations, suggests that CHIKV failed to achieve effective amplification within the local mosquito population.

In conclusion, this outbreak demonstrates that in non-endemic areas harboring competent vectors, CHIKV can rapidly establish local transmission following case importation. Public health efforts must prioritize the rapid detection of imported viremic cases, precise mapping of their exposure sites, and immediate implementation of intensive, targeted vector control measures within a critical time window to interrupt transmission. Future multi-center studies incorporating larger sample sizes and integrated entomological surveillance are essential to deepen our understanding of transmission dynamics across diverse settings.

HTML

Epidemiological Investigation

Contact Tracing of Co-exposed Individuals and Infection Source Investigation

Molecular Epidemiological Analysis

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: