-

Introduction: This study investigated the causes and transmission pathways of an infectious diarrhea outbreak at a high school in Baisha County during November 2024 to inform response strategies for similar outbreaks.

Methods: Field epidemiological methods were employed to investigate and characterize the outbreak’s epidemic features, while risk factors were analyzed through a case-control study. Case specimens underwent multipathogen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) chip screening combined with real-time fluorescent PCR to identify the causative pathogen. Reserved cafeteria food samples were tested for diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC)-specific virulence genes using real-time fluorescent PCR. Environmental water samples were analyzed by the culture method (1) to quantify total bacterial count, total coliforms, and Escherichia coli.

Results: A total of 344 cases were identified, yielding an attack rate of 11.44%. The most common clinical manifestations were diarrhea (80.23%) and abdominal pain (76.74%). Attack rates showed no statistically significant differences by gender or between boarding and day students (P>0.05). Case-control analysis demonstrated that consumption of school-provided direct drinking water was the primary risk factor for illness (odds ratio=3.87, 95% confidence interval: 1.18, 12.68). Laboratory testing identified DEC in both patient specimens and inlet tap water samples from the dispensers; the DEC positivity rate in patient specimens reached 63.3% (19/30), with escV and pic+astA as the predominant virulence genes (either singly or in combination). Hygienic surveys revealed that the school’s direct drinking water dispensers failed to meet required standards; after these dispensers were deactivated, the incidence of new cases declined markedly.

Conclusion: This outbreak was caused by DEC. The primary transmission route was consumption of direct drinking water supplied by substandard dispensers using contaminated source water, with person-to-person transmission occurring during the later stages of the outbreak.

-

On November 12, 2024, the Baisha County CDC received notification from the County Education Bureau regarding multiple students at a local high school presenting with diarrhea and vomiting. County CDC public health professionals were promptly dispatched to the school for on-site verification. Rectal swabs collected from affected patients were analyzed using a multiplex pathogen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) array, with results confirming the presence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC). To enable comprehensive source tracing and outbreak containment, six technical specialists from the provincial CDC were deployed on November 15 to conduct a joint field investigation.

-

The affected senior high school in Baisha County has 60 classes across three grades, with a total of 3,006 students enrolled and 308 faculty and staff members, including one school doctor. Beginning November 6, 2024, acute gastroenteritis cases emerged sporadically, followed by a sharp increase in case numbers.

We defined a suspected case as diarrhea (≥3 episodes/24 hours) and/or vomiting (≥2 episodes/24 hours) with onset on or after November 4, 2024, in the school community. A confirmed case required laboratory detection of DEC in a relevant clinical specimen. Cases were identified by cross-referencing school reports with student absenteeism records, medical consultation logs, and interviews with school and cafeteria personnel.

A total of 344 ill students were identified, with an attack rate of 11.44%. The predominant clinical manifestations were diarrhea (80.23%, 276/344), abdominal pain (76.74%, 264/344), nausea (60.76%, 209/344), and vomiting (44.48%, 153/344). Most cases experienced 3 episodes of diarrhea daily (44.77%), followed by 4 episodes daily (17.44%), with 5–8 episodes daily accounting for 18.02%. Similarly, vomiting occurred most commonly at 2 episodes daily (26.45%), followed by 3 episodes daily (10.47%), with 4–6 episodes daily accounting for 7.56%. Fever was uncommon (2.33%, 8/344), and no cases required hospitalization or progressed to severe illness.

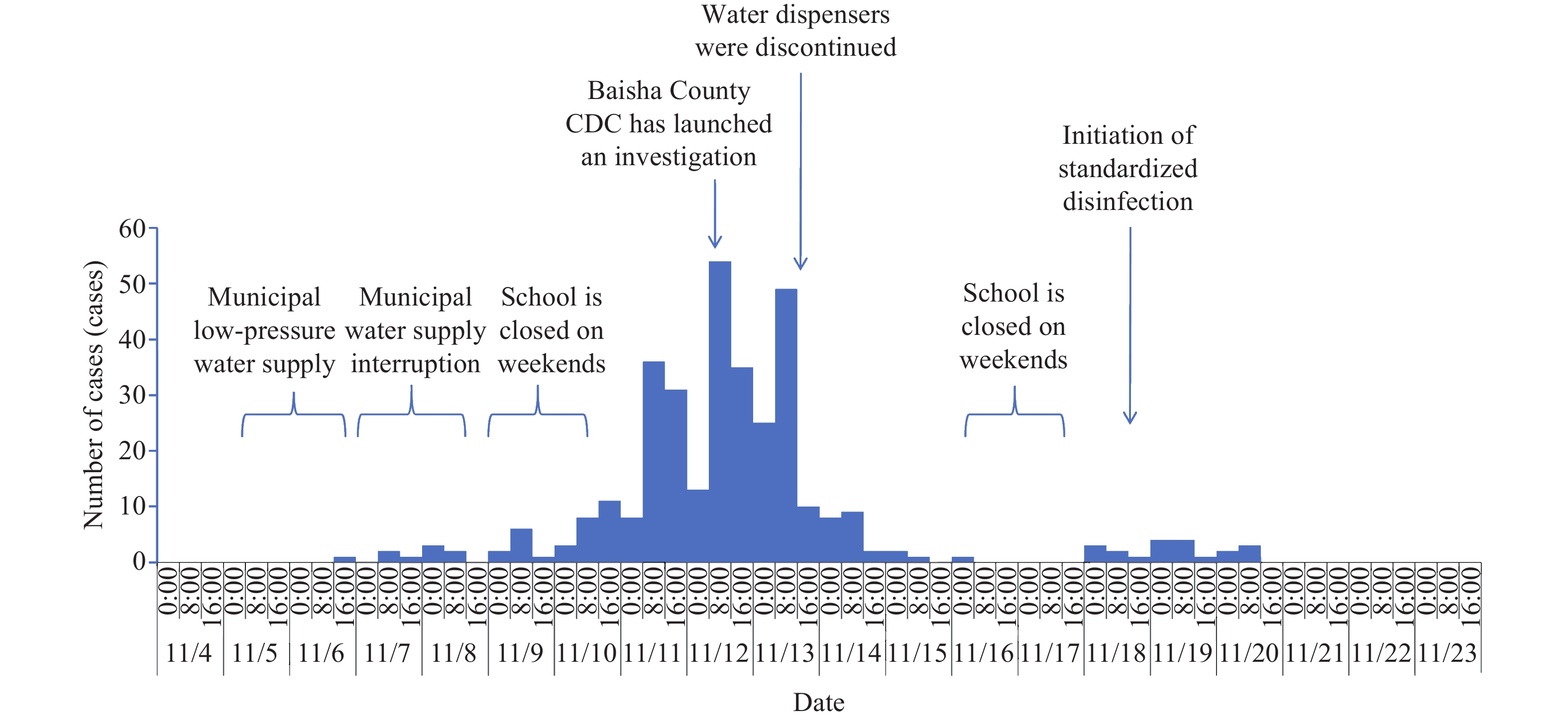

The index case developed symptoms at 21:30 on November 6 and was a boarding student from Class 6, Grade 10. This case had no history of dining outside the school or consuming raw food within 3 days prior to onset. The epidemic curve indicated sustained common-exposure transmission, with cases predominantly concentrated between November 11 and 13 (75.87%, 261/344) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Epidemic curve of the infectious diarrhea outbreak at a high school in Baisha County, November 2024.

Among the 344 cases, attack rates showed no significant differences by gender (male: 11.89%, n=160; female: 11.08%, n=184) or boarding status (boarders: 12.13%, n=259; day students: 9.75%, n=85). Although day students did not consume cafeteria meals, they did drink water from the on-campus dispensers. The absence of statistical significance (P>0.05) across these comparisons preliminarily excluded foodborne transmission, identifying direct drinking water as the probable transmission vehicle.

No cases occurred among faculty and staff. Although faculty and staff shared identical cafeteria meals with students at the two on-campus dining facilities, they consumed their own boiled water rather than water from the dispensers used by students. This key distinction further ruled out cafeteria meals as the outbreak source and reinforced the identification of students’ drinking water as the likely vehicle of transmission.

Based on the descriptive epidemiological analysis, we conducted a case-control study enrolling 60 early-onset cases matched 1∶1 by age (±1 year) and class with 60 healthy controls. Data were collected using a standardized, purpose-designed questionnaire. Univariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that consumption of direct drinking water constituted a significant risk factor [odds ratio (OR)=3.87, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.18, 12.68]. Conversely, no statistical associations were observed between illness and consumption of raw food, cafeteria meals, or boarding status (P>0.05) (Table 1).

Exposure factors Case group (n=60) Control group (n=60) P OR (95% CI) Cases Percentage (%) Cases Percentage (%) Consumption of water from direct

drinking water dispensers56 93.33 47 78.33 0.025 3.872 (1.183, 12.676) Consumption of raw food 4 6.67 3 5.00 0.698 1.357 (0.290, 6.341) Consumption of school cafeteria meals 46 76.67 48 80.00 0.658 0.821 (0.344, 1.962) Boarding status 49 81.67 46 76.67 0.501 1.356 (0.559, 3.289) Abbreviation: OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval. Table 1. Case-control study of an infectious diarrhea outbreak at a high school in Baisha County, November 2024.

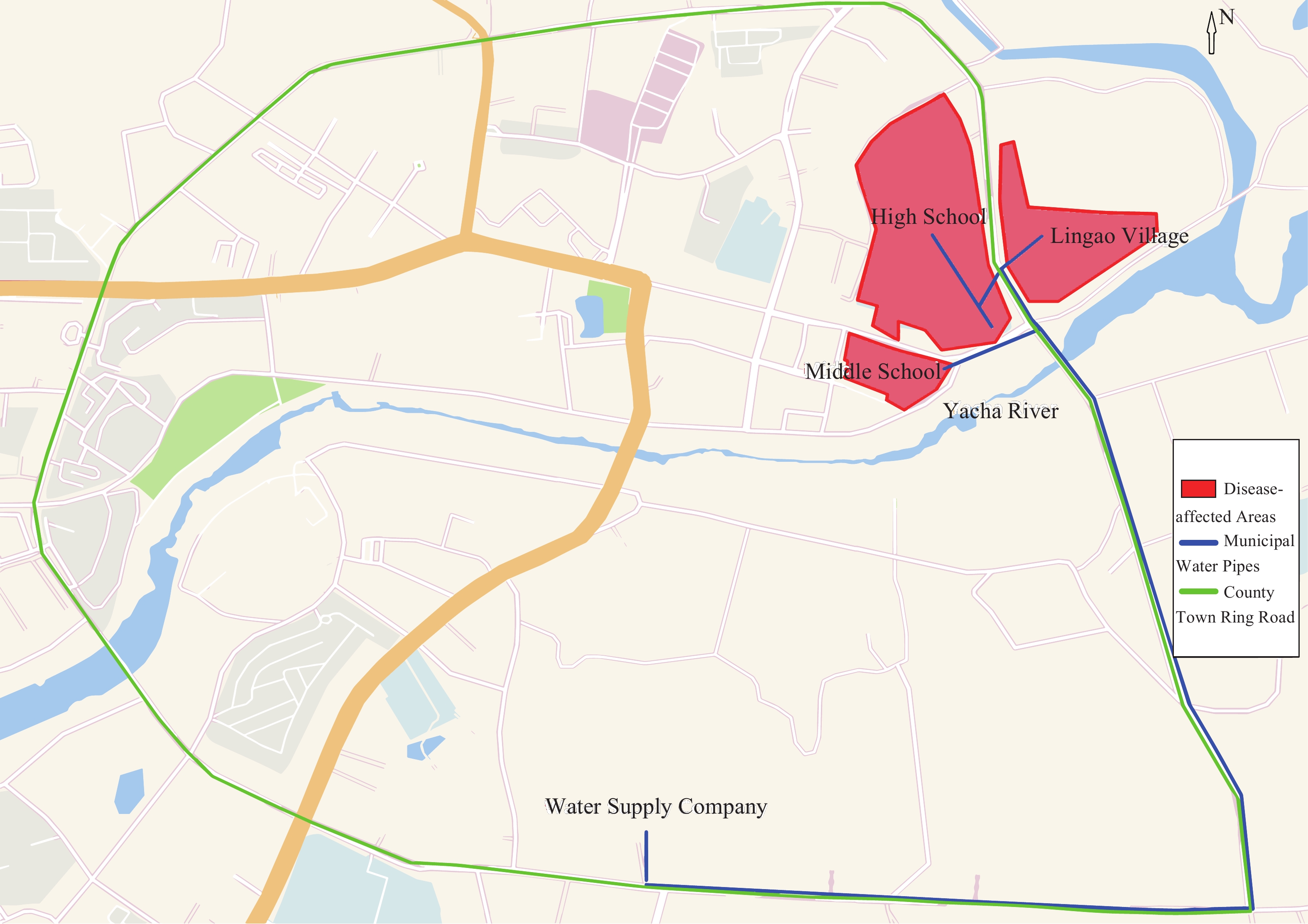

Environmental investigation revealed that the senior high school received municipal water supply through a pipeline passing beneath the Yacha River. This same water source served a neighboring junior high school and nearby village residents (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.Spatial configuration of the municipal water distribution infrastructure in Baisha County.

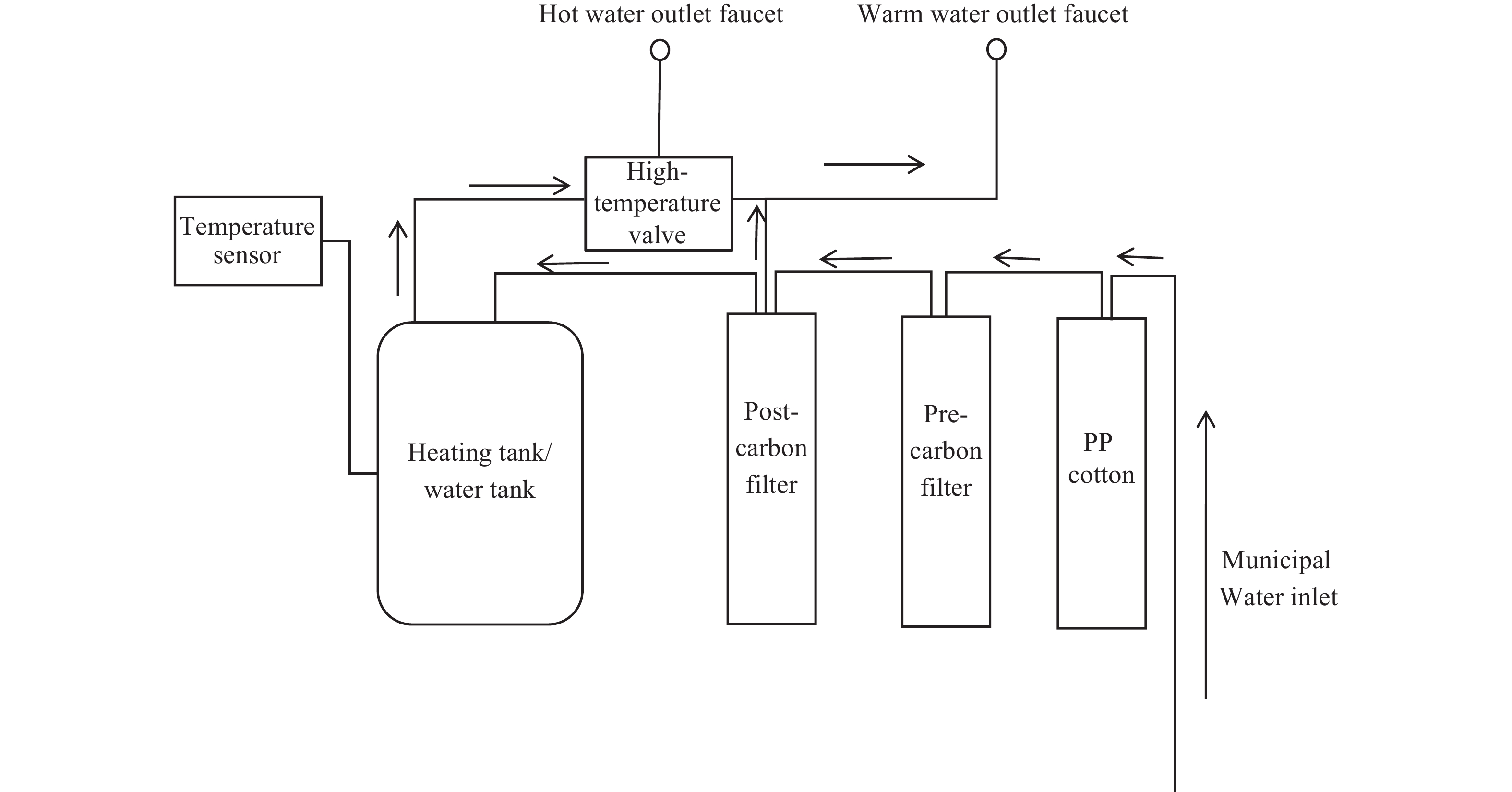

The municipal water supply experienced low pressure from November 5 to 6, 2024, followed by complete shutdown from November 7 to 8, 2024. Field testing conducted on November 14 and 17 demonstrated that residual chlorine in endpoint water samples from the school’s security office and teaching buildings was undetectable (0 mg/L). Furthermore, the school’s direct drinking water dispensers were equipped only with PP cotton, pre-filter carbon, and post-filter carbon filters, lacking the critical ultrafiltration or reverse osmosis membranes necessary for effectively removing bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms. The filters had not been replaced every 3 to 6 months as required by the instruction manual; instead, only simple cleaning was conducted without thorough disinfection before the start of the semester. Physical inspections revealed severe contamination of the internal filters. The water quality was turbid. The “warm water” supplied to students was produced by mixing filtered cold water with heated water (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Figure 3.Purification process of the water dispensers at a high school in Baisha County, November 2024.

Abbreviation: PP=polypropylene.To further trace the outbreak source, the investigation team conducted an expanded survey of additional off-campus schools and surrounding communities on November 17. A neighboring junior high school (943 students total) that shared the same municipal water source and utilized the same model of direct drinking water dispensers reported 55 students experiencing symptoms including diarrhea and abdominal pain beginning November 8, yielding an attack rate of 5.83%. One affected student tested positive for DEC during medical consultation. Among 272 residents in the adjacent community, 6 sporadic cases occurred between November 1 and 17, representing a significant increase compared with the same period in the previous month (0 cases). No similar outbreaks were identified in the municipal water supply area upstream of the Yacha River, including schools and communities within that region.

Laboratory testing demonstrated that among 30 rectal swab samples from ill students, 19 tested positive for DEC (positivity rate: 63.3%), with the uidA gene detected in all positive samples. The predominant virulence genes identified were escV and pic+astA (either alone or in combination). Among 43 drinking water samples analyzed, 1 municipal terminal water sample collected from the school’s security office on November 14 (before entering the direct drinking water dispensers) tested positive for Escherichia coli. Five water samples collected from the filter containers of Direct Drinking Water Dispensers No. 1 and No. 2 on the first floor of Teaching Buildings 1 and 2, and Dispenser No. 7 on November 15 and 18 exhibited excessive total bacterial counts. Four water samples collected on November 18 — including those from a community resident’s home, the terminal water of a canteen faucet in the junior high school, and the filter containers of two direct drinking water dispensers on the second floor of the teaching building — demonstrated excessive total coliforms. All 93 reserved food samples from the canteen tested negative for DEC virulence genes.

Following the hypothesis that drinking water contamination was driving the outbreak, the school deactivated all direct drinking water dispensers on November 14, resulting in a sharp decline in new cases. However, because terminal disinfection was not properly implemented in classrooms, dormitories, and toilets according to established standards, 20 additional cases emerged between November 18 and 20 after students returned to school. Among these later cases, 19 had documented contact with diarrheal patients prior to symptom onset: 8 cases shared both classrooms and dormitories with infected students, 3 cases attended the same classes as infected students but resided in different dormitories, 7 cases belonged to different classes but shared toilets on the same floor with infected students, and 1 case had close contact with an infected peer. These epidemiological patterns strongly suggest that person-to-person transmission accounted for these secondary cases.

-

Case management protocols required a 3-day home isolation for all affected individuals. Substandard direct drinking water dispensers were immediately deactivated, and boiled drinking water from the cafeteria was provided as an alternative. Following the emergence of additional cases on November 18, trained cleaning staff were deployed to perform disinfection of public areas twice daily, while standardized procedures for disposal of students’ vomitus and feces were implemented. Concurrently, the daily epidemic reporting system was rigorously enforced, and both health education initiatives and risk communication strategies were intensified. These comprehensive control measures successfully contained the outbreak.

-

Integrated findings from field, environmental, and laboratory investigations confirmed this outbreak as a DEC infection associated with consumption of drinking water supplied by substandard water dispensers that inadequately filtered contaminated municipal water (2). The probable contamination source was river water infiltration into the municipal water supply pipeline — which passes beneath a river — during periods of low-pressure water supply and service interruption. Person-to-person transmission subsequently occurred during the later stages of the outbreak. The principal supporting evidence is as follows:

1) Foodborne transmission was definitively excluded. Faculty and staff consumed identical cafeteria meals as students but remained unaffected. Attack rates showed no statistically significant difference between boarding students and day students (who did not consume cafeteria meals). The case-control study revealed no association between specific cafeteria meals or food items and illness onset. Furthermore, all retained food samples from the cafeteria tested negative for DEC.

2) Multiple lines of evidence support waterborne transmission through contaminated drinking water. First, faculty and staff who consumed only boiled water rather than dispenser water remained unaffected, whereas students who consumed dispenser water experienced high attack rates regardless of boarding status. The case-control study identified dispenser water consumption as a significant risk factor for illness. Second, according to relevant standards (3), public terminal direct drinking water dispensers should be equipped with high-efficiency purification filter elements such as ultrafiltration membranes or nanofiltration membranes. However, the direct drinking water dispensers in this school were equipped only with PP cotton, pre-filter carbon, and post-filter carbon filters, failing to meet these requirements. Additionally, inadequate maintenance rendered them unable to effectively remove microorganisms. Following deactivation of the direct drinking water dispensers, the number of cases declined sharply. Third, Escherichia coli was detected in water samples from the school’s security office, and on-site testing revealed zero residual chlorine, indicating that the supplied tap water failed to meet safety standards and that the water source was continuously contaminated. Finally, Jiang Haibo et al. (4) demonstrated that intermittent water supply can generate negative pressure in water supply pipelines, and the resulting back-siphonage can allow sewage infiltration from outside the pipeline. Source-tracing investigation revealed that a neighboring junior high school using the same municipal water source also experienced a similar diarrheal outbreak, suggesting that river water infiltration occurred due to negative pressure during periods of municipal low-pressure water supply and water suspension.

3) Person-to-person transmission was also documented in the later phase of the outbreak. Sporadic cases emerged after November 18, with 95% of these cases having clear contact history with diarrheal cases prior to onset, indicating that interpersonal contact transmission became the primary transmission route for these subsequent cases.

DEC represents a major pathogen responsible for diarrheal outbreaks in China (5). It can be transmitted through food, water, and person-to-person contact (6–9), characterized by rapid onset and a high propensity to cause clustered infections. This investigation confirmed that the outbreak of infectious diarrhea was associated with consumption of drinking water supplied by substandard direct drinking water dispensers that inadequately filtered contaminated tap water.

Similar reports are rare in China. Lu Rutou et al. (10) documented in 2006 the only comparable incident — an infectious diarrhea outbreak in a school caused by direct drinking water dispensers that failed to meet hygienic requirements. In that case, filters were neither replaced nor disinfected regularly, receiving only superficial cleaning.

Direct drinking water dispensers are now widely deployed in collective settings throughout China, particularly in schools and other institutional facilities. However, most dispensers provide only filtration functions and generally lack disinfection and sterilization capabilities (11). When water sources fail to meet quality standards and dispenser products do not comply with national requirements, drinking water safety cannot be assured, creating conditions conducive to infectious diarrhea outbreaks.

Therefore, schools and other collective institutions should use direct drinking water dispensers only when water sources are demonstrably safe. They must purchase dispensers that meet national standards and conduct regular maintenance as specified by manufacturers and regulatory requirements.

At the government level, a multi-department collaborative prevention and control mechanism for diarrheal outbreaks should be established with clearly defined responsibilities: health commissions and CDC should implement health monitoring and provide emergency technical guidance; water authorities should strengthen routine supervision of drinking water systems to ensure source water safety; market supervision departments should rigorously control the quality of direct drinking water dispensers entering the market; education departments should oversee all aspects of centralized procurement of direct drinking water dispensers in schools; water supply companies should notify schools in advance of planned water suspensions and immediately investigate suspected pipeline contamination; when outbreaks occur, schools should report promptly, designate trained personnel for daily dispenser maintenance, and arrange for thorough cleaning and disinfection of dispensers before resuming water supply following municipal low-pressure events or water suspensions. This coordinated regulatory framework should ensure clear division of responsibilities and efficient inter-departmental collaboration.

This investigation has an important limitation: the Baisha County Center for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory lacked gene sequencing capabilities, preventing genetic sequencing and homology analysis of DEC strains isolated from patient specimens and environmental samples. This technical constraint precluded molecular-level confirmation that environmental pathogens and those causing human infections shared a common source, leaving the etiological association without direct molecular evidence.

This investigation demonstrates that contaminated water sources combined with inadequately equipped direct drinking water dispensers — lacking sufficient filtration capacity to remove bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms — compromise drinking water safety and facilitate clustered infection outbreaks. To prevent similar incidents, we advise all sectors of society, particularly collective institutions such as schools, to purchase only compliant direct drinking water dispensers and to use such equipment exclusively when water sources meet safety standards. Furthermore, molecular tracing technology should be prioritized as a critical component of future outbreak investigations.

-

All colleagues at the Hainan Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the Baisha County Center for Disease Control and Prevention for their invaluable technical assistance and steadfast support throughout this outbreak investigation.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: