-

Objective: To report the first imported case of cerebral schistosomiasis mansoni in China and highlight the public health risks posed by this disease.

Methods: We conducted an epidemiological investigation, performed laboratory testing of clinical samples, and collected diagnostic and treatment data. The infection source was determined through comprehensive analysis of epidemiological history, clinical manifestations, and laboratory findings.

Results: Before returning to China, the patient had resided for nearly 10 years in schistosomiasis-endemic regions, including Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where mountain spring water was used for drinking and daily activities. One month before returning to China, the patient developed central nervous system symptoms, including limb weakness and slowed reactions. Laboratory testing revealed markedly elevated eosinophil (EOS) levels, with both percentage (25.0%) and absolute count (3.30×109/L) exceeding normal ranges. High-throughput sequencing (HTS) of blood samples identified Schistosoma mansoni DNA sequences, and microscopic stool examination detected S. mansoni eggs.

Conclusion: China is not an endemic area for S. mansoni. This study reports the first imported case of cerebral schistosomiasis mansoni in China. With the continuous emergence of imported S. mansoni cases and the gradual expansion of intermediate host breeding grounds, we should actively monitor the potential risk of local transmission occurring in China. Enhanced protective awareness among outbound tourists and strengthened public health surveillance are essential measures to counter the threat posed by imported cases.

-

Schistosomiasis mansoni is a parasitic disease caused by adult Schistosoma mansoni parasites inhabiting venous vessels, including mesenteric small veins and hemorrhoidal venous plexuses. Primary clinical manifestations include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hepatosplenomegaly (1). The disease predominantly affects populations in Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean region, and Central and South America (2), with approximately 54 million people infected worldwide annually (3–4). China is endemic for Schistosoma japonicum infection but not for S. mansoni infection (5).

In May 2025, the Henan CDC received a report of one suspected case of schistosomiasis mansoni. Based on clinical symptoms, epidemiological findings, pathogen identification, and molecular biology evidence, this case was confirmed as an imported case of cerebral schistosomiasis mansoni.

This case underscores the critical importance of early detection and surveillance of imported schistosomiasis mansoni cases in China and reveals emerging public health challenges associated with increased international travel and global connectivity.

-

In May 2025, a hospital in Henan Province, China, reported a 51-year-old male worker as a suspected case of parasitic disease, presenting with central nervous system symptoms and blood eosinophilia. After excluding cerebral infarction, the case was definitively diagnosed as S. mansoni infection based on multiple lines of evidence: detection of eggs in stool samples, clinical presentation, epidemiological history, etiological findings, and high-throughput sequencing (HTS) testing of blood samples. Following one month of praziquantel treatment, S. mansoni eggs were no longer detectable in the patient’s stool.

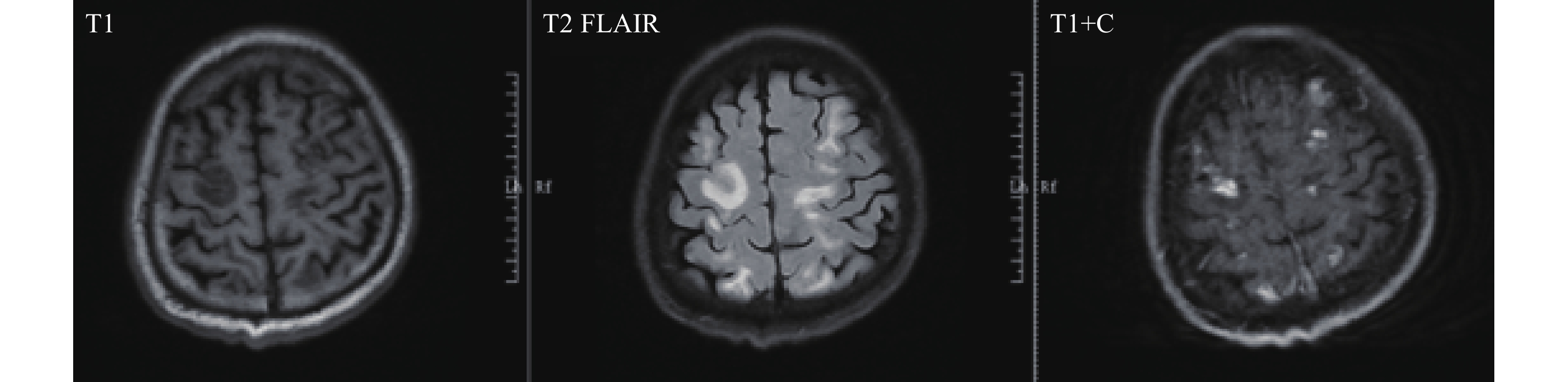

Notably, the patient did not present with typical schistosomiasis symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or hepatosplenomegaly. Instead, central nervous system manifestations emerged in April 2025, including limb weakness, slowed reaction time, memory impairment, and loss of independent ambulation. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed extensive FLAIR hyperintensities throughout the bilateral frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes, with additional involvement of the brainstem and cerebellum. Hemosiderin deposition was noted in the bilateral frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes and the left cerebellar hemisphere. Hypointensity were also observed in the bilateral globus pallidus, suggesting mineral deposition or calcification (Figure 1). Central nervous system lesions resulting from ectopic egg migration can manifest without the more common hepatointestinal symptoms, potentially complicating clinical suspicion of schistosomiasis.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.MRI findings reveal multiple symmetrical abnormal signals in the bilateral frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes, as well as the periventricular regions of the bilateral lateral ventricles.

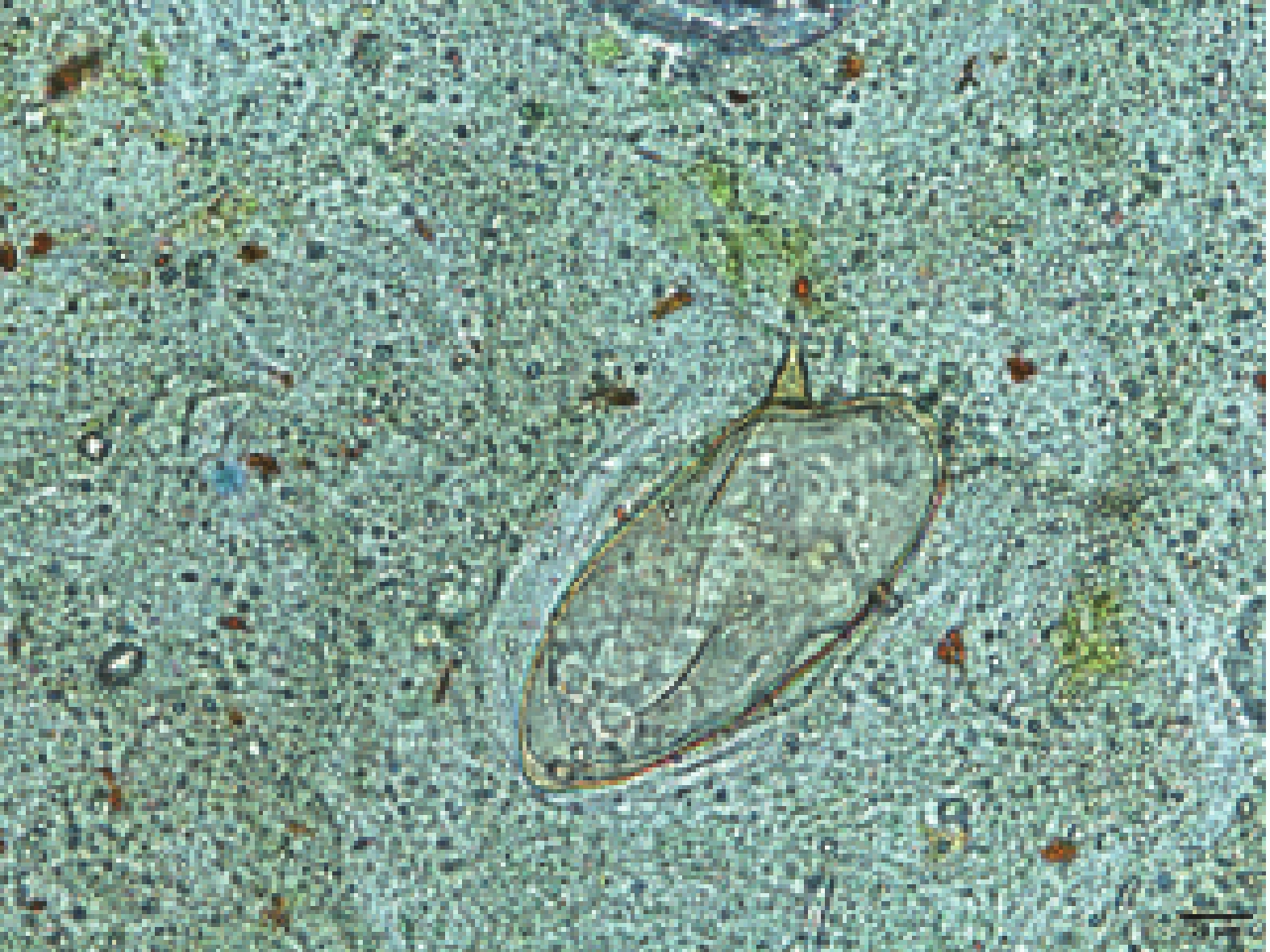

Abbreviation: MRI=magnetic resonance imaging.Routine blood testing demonstrated marked eosinophilia, with both the percentage (25.0%) and absolute count (3.30×109/L) exceeding normal reference ranges. HTS analysis of blood samples identified four sequences of S. mansoni. Fecal examination employed three methods: automated routine analysis, the egg-hatching method following nylon mesh bag concentration, and the modified Kato-Katz thick smear technique. Automated stool analysis failed to detect any eggs, and the egg-hatching method revealed no miracidia. Using the Kato-Katz technique, examination of three fecal smears yielded no S. mansoni eggs; however, continued testing of an additional seven smears (10 total) identified a single egg (Figure 2). These combined findings provided definitive etiological evidence for diagnosis.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.Egg detected at Kato-Katz thick-smear preparations, 400×magnification.

Note: The lateral subterminal spine is the character of S. mansoni eggs.Epidemiologically, the patient had worked in schistosomiasis-endemic regions, including Angola from 2013 to 2024, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from December 2024 to April 2025. While in the DRC, the patient had frequent contact with local mountain spring water, which served as the primary source for both drinking and daily household use. Although intermediate host breeding grounds have emerged in southern China, the country remains non-endemic for schistosomiasis mansoni. Consequently, this case represents an S. mansoni infection acquired in Africa.

Retrospective investigation revealed that in April 2025, while still abroad, the patient exhibited a markedly elevated eosinophil (EOS) percentage (47%) accompanied by right-sided limb weakness and sluggish responsiveness. Despite these findings, the patient was diagnosed with cerebral infarction. Symptomatic treatment failed to produce clinical improvement. Upon returning to China, the EOS percentage remained elevated at 30%; however, municipal-level medical institutions where the patient first sought treatment did not consider parasitic infection as a differential diagnosis after excluding cerebral infarction. Provincial medical institutions subsequently employed HTS testing based on routine blood test results to guide the diagnostic workup, which was ultimately confirmed through the detection of parasite eggs in stool samples examined at the Henan CDC.

-

Most S. mansoni infections present primarily with gastrointestinal manifestations, including abdominal pain and diarrhea (1,6-7). Severe infections may progress to portal hypertension and esophageal variceal bleeding (3). Within the nervous system, schistosomiasis mansoni predominantly affects the spinal cord (8). Although a limited number of cerebral schistosomiasis cases have been documented in Brazil and other regions (9-12), the present case represents the first such report from China. This case provides valuable clinical insights for diagnosing similar presentations in the future.

Definitive diagnosis of S. mansoni infection requires detection of S. mansoni eggs or miracidia in fecal examinations or tissue biopsies (13). The Kato-Katz thick smear technique represents a widely used method for detecting parasite eggs in stool samples and remains suitable for laboratory diagnosis of most intestinal parasitic infections. In this case, direct smear examination and nylon mesh bag concentration failed to detect pathogens, and only a single egg was identified in one Kato-Katz slide among ten slides examined. Given that S. mansoni produces only one-fifth to one-tenth the number of eggs compared with Schistosoma japonicum, this low egg burden presents significant diagnostic challenges that laboratory personnel must recognize. Furthermore, HTS has demonstrated an invaluable role in guiding clinical diagnosis of rare or atypically presenting parasitic infections (14-15).

Despite blood test results suggesting possible parasitic infection when neurological symptoms emerged, municipal-level hospitals did not initially pursue parasitic antibody or pathogen screening upon case admission. This observation suggests that enhanced training in recognizing imported parasitic diseases may be needed at the primary care level, particularly for rare and imported infectious diseases.

In conclusion, this study documents the first imported case of cerebral schistosomiasis mansoni in China and underscores the potential threat of local transmission from imported cases. With the continuous emergence of imported S. mansoni cases and the gradual expansion of intermediate host breeding grounds, we should actively monitor the potential risk of local transmission occurring in China. Primary medical institutions and CDCs must strengthen their capacity for preventing and controlling imported cases from Africa and other endemic regions, while simultaneously enhancing laboratory testing capabilities. Strengthening the integration of medical and preventive measures, improving the sensitivity of sentinel surveillance at the primary care level, and preventing clinical misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis will effectively reduce the risk of local transmission triggered by imported cases.

-

The team at the Department of Neurology at the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University for their support during the epidemiological investigation of this case.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: