-

Rabies is an acute zoonotic disease caused by the rabies virus, clinically characterized by specific symptoms such as hydrophobia, aerophobia, agitation, and progressive paralysis. Once developed, the disease fatality rate is 100% (1). Rabies is highly endemic in Hunan Province, China. Although its incidence has decreased in recent years, the annual number of cases has always been among the highest in China, indicating a serious situation (2). Standardized and timely post-exposure wound management, vaccination, and the use of passive immunization preparations, if necessary, are key measures for preventing rabies. However, instances of post-exposure prophylactic failure (PEP) occasionally occur because of various influencing factors (3).

To understand the epidemiological characteristics of rabies and PEP failure cases in Hunan Province in recent years, information on rabies cases from 2019 to 2024 was organized and analyzed to provide a reference for future rabies prevention and control.

-

Case data were derived from surveillance data reported to the China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention (CISDCP) and rabies case investigation records (2019–2024) in Hunan Province. When receiving reports of rabies cases from medical institutions, the local disease control center conducted epidemiological investigations on the cases and fills out the “Rabies Case Investigation Form,” which includes the following: demographic characteristics; degree and location of wound exposure and disposal measures; use of rabies vaccine prophylaxis and passive immunization preparations; and characteristics of the animals causing exposure. Demographic data were obtained from the Hunan Statistical Compendium.

-

Rabies diagnosis adhered to the Diagnostic Criteria for Rabies (WS 281-2008). The exposure severity was categorized according to the Work Specification for Rabies Exposure Prophylaxis and Disposal (2023 Edition) (4). A case of PEP failure was defined as a rabies death occurring despite receiving at least one of the following medical interventions after exposure: wound irrigation, rabies vaccination, or administration of passive immunizztion preparations (5–6).

-

Data on rabies cases (2019–2024) in Hunan Province were collected and entered using EpiData software (version 3.1, Epidata Association, Denmark) and processed in Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). SPSS Statistics (version 26.0, IBM, NY, USA) was then used to statistically describe and analyze the characteristics of rabies incidence and PEP failure cases. The overall incidence of rabies and the percentage of PEP failure cases were tested using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. The incubation period was described using median (Q1, Q3), and a comparative analysis was performed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

-

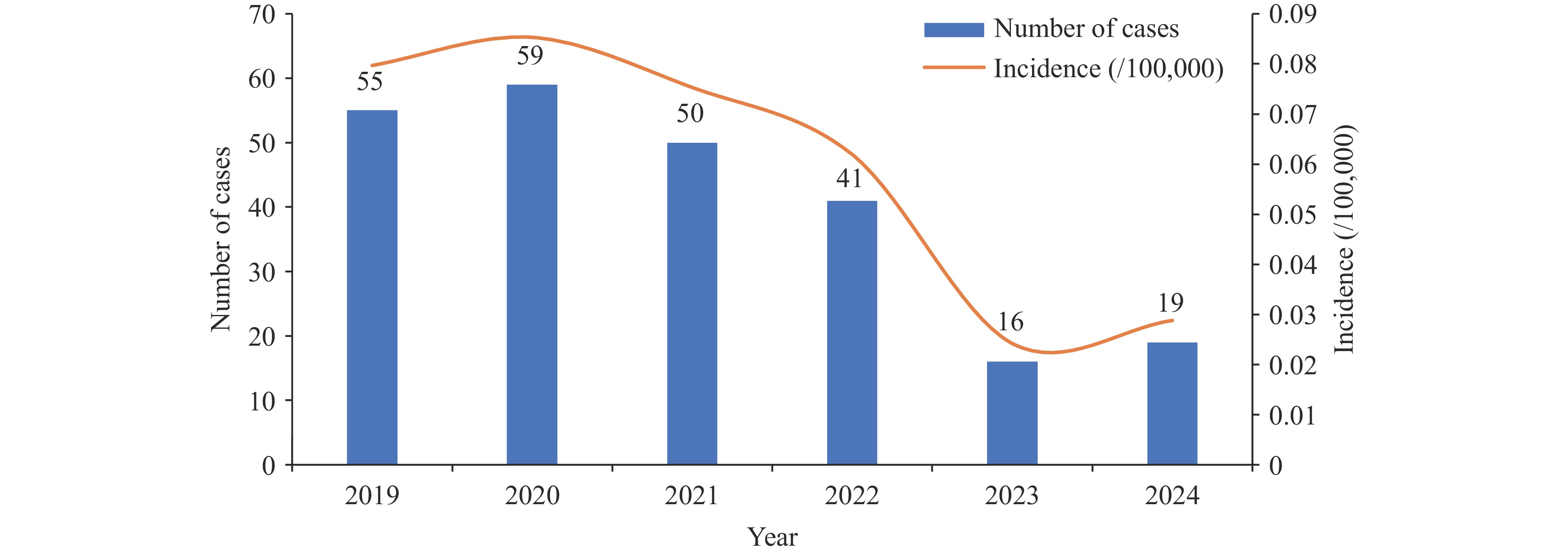

Hunan Province reported 240 rabies cases between 2019 and 2024, including 128 clinically diagnosed and 112 laboratory-confirmed cases. The average annual incidence was 0.0592 per 100,000 individuals. A significant downward trend was observed over the study period (χ2trend=32.72, P<0.05) (Figure 1).

-

The highest number of cases was reported between July and October, with 102 cases accounting for 42.5% of the total. Cases were reported across all 14 prefectures, predominantly clustered in Shaoyang (77, 32.08%), Yongzhou (72, 30.00%), and Loudi (21, 8.75%). Males (n=170) outnumbered females (n=70) (male-to-female ratio: 2.43∶1). Their ages ranged from 2 to 90 years, with 65.42% (157/240) being concentrated in the 50–79 years age group. The majority comprised farmers (184, 76.67%), followed by students (26, 10.83%) and non-institutionalized children (13, 5.42%).

-

Among the 240 cases, dogs accounted for 218 exposures (90.83%) and cats for 8 (3.33%), with the source unknown in 14 (5.83%) cases. Animal origins included household-owned (121/240, 50.42%), stray (63/240, 26.25%), and neighbor-owned (30/240, 12.50%) animals. Animal-initiated attacks, playing with animals, and animal self-defense injuries were the primary causes of injury, accounting for 35.42% of all injuries.

-

Bites were the primary route of exposure (184/240, 76.67%), followed by scratches (20/240, 8.33%). The exposure severity was predominantly category III (156/240, 65.00%) or II (16/240, 6.67%). The exposure positions were categorized as such: hands (131/240, 54.58%); lower limbs distal to the knee (35/240, 14.58%); and head/face/neck complex (15/240, 6.25%). Wound management status was as follows: no intervention (141/240, 58.75%); self-managed (77/240, 32.08%); and clinical management (22/240, 9.17%).

-

Among the 235 cases investigated for exposure immunization, none had a history of pre-exposure immunization. Eighteen (7.66%) patients were vaccinated with the human rabies virus vaccine after exposure. For category III exposures, 11/156 cases (7.05%) were administered passive immunization preparations.

-

Among the 177 cases with confirmed incubation periods, the incubation period showed a right-skewed distribution (range: 1–1,774 days; median, 60 days). Non-parametric tests were used to analyze the influencing factors on the incubation period. The results showed that differences in the influences of five factors on the incubation period — exposure site, wound management, vaccination after exposure, passive immunization preparations, and the sources of the animal causing exposure — were statistically significant (P<0.05) (Table 1).

Variables Number of rabies cases (n) Proportion (%) Incubation period Mean rank Statistic (H/U) P Median (day) Q1–Q3 Exposure type Bite 154 87.01 65 30–133 90.52 4.169 0.244 Scratch 14 7.91 60.5 32.5–150 88.75 Lick 4 2.26 23 † 37.88 Not specified 5 2.82 75 30–85 83.9 Exposure category Category Ⅲ 135 76.27 58 31–124.5 87.44 1.431 0.489 Category Ⅱ 14 7.91 90 51.75–196.75 104.64 Not specified 28 15.82 65.5 31–99.75 88.7 Exposure site Hands 113 63.84 64 37–150 96.56 28.763 <0.001* Lower limbs below knee 25 14.12 42 24–71 64.22 Head and/or face 15 8.47 16 14–22.5 26.67 Lower limbs above knee 9 5.08 64 50–157 102.5 Trunk 3 1.69 60 † 99.33 Not specified 12 6.78 42 30–165 83.63 Wound management No intervention 88 49.72 73 39–150.25 100.24 25.507 <0.001* Self-managed 68 38.42 60 32–120 90.36 Clinical management 21 11.86 22 14–31 37.50 Post-exposure vaccination Yes 17 9.60 63.5 34–150 95.12 381.500 <0.001* No 160 90.40 16 14–24 31.44 Post-exposure injection of passive immunization preparations Yes 11 6.21 60 32–141.5 92.32 362.500 0.001* No 166 93.79 16 14–36 38.95 Types of animals causing exposure Dog 171 96.61 60 31–129.5 88.35 402.000 0.368 Cat 6 3.39 77 50.75–133.25 107.50 Sources of animals causing exposure Household-owned 95 53.67 65 39–135 95.51 13.707 0.003* Neighbor-owned 24 13.56 55 23.25–152.5 83.67 Stray 51 28.81 39 30–67 72.54 Not specified 7 3.95 210 150–438 138.93 * There are statistically significant differences between different groups of variables.

† The interquartile spacing could not be determined because the sample size was extremely small.Table 1. The distribution of incubation period of rabies cases in Hunan Province, 2019–2024 (n=177).

-

Among the 240 rabies cases (2019–2024), 22 PEP failures (9.17%) occurred, primarily in Shaoyang (nine cases) and Loudi (four cases). There was no increasing trend in the proportion of PEP failure in the last six years as a percentage of all rabies cases in that year (χ2trend=1.809, P=0.86).

Of the 22 cases of PEP failure, 15 were clinically diagnosed, seven were laboratory-confirmed, 18 were category III exposures, and four were of unknown exposure levels. There were 11 cases (50.00%) of head and/or face exposure, seven cases (31.82%) of hand exposure, and four cases (18.18%) of lower extremity exposure above and below the knee. Among all cases of PEP failure, 18 were vaccinated and 15 did not complete the full vaccination because they died after the onset of the disease. Additionally, three cases of category III exposure were involved in all aspects of PEP (wound management, vaccination, and administration of passive immunization preparations). The distribution of the PEP interventions by calendar year is shown in Table 2.

Year Total cases PEP failure cases Proportion of cases in the current year (%) PEP interventions Wound management only Wound management + Not fully vaccinated Wound management + Full vaccination Wound management + Passive immunization preparations + Not fully vaccinated Wound management + Passive immunization preparations + Full vaccination 2019 55 4 7.27 2 0 0 2 0 2020 59 5 8.47 1 0 0 4 0 2021 50 4 8.00 1 2 0 1 0 2022 41 5 12.20 0 4 0 0 1 2023 16 1 6.25 0 0 0 1 0 2024 19 3 15.79 0 1 0 0 2 Total 240 22 9.17 4 7 0 8 3 Abbreviation: PEP=post-exposure prophylaxis. Table 2. The distribution of PEP interventions among PEP failure cases in Hunan Province, 2019–2024.

We also investigated the time from exposure to wound management in cases of PEP failure. Eighteen cases (81.82%) were treated on the day of exposure, while the remaining four cases were treated within 2–3 days after exposure. The shortest incubation period of PEP failure cases was two days, the longest was 209 days, and the incubation period was within three months in 16 cases (88.89%), with a median incubation period of 23.0 (14.0, 31.0) days. The median incubation period of failed PEP cases with exposed areas including head and/or face was 16.0 (14.0, 22.0) days, while it was 31.0 (24.0, 50.0) days for those without such exposure, with a statistically significant difference observed (U=20.50, P=0.025).

-

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the trend of rabies incidence and the characteristics of cases with PEP failure from 2019–2024 in Hunan Province. Consequently, we found that the rabies epidemic in Hunan was in line with the development trend of rabies epidemics in China (2).

Notably, the temporal distribution of rabies in Hunan Province between 2019 and 2024 was consistent with other researchers’ findings, with a higher number of cases occurring in summer and autumn (7). The regional distribution was dominated by traditional rabies-endemic cities such as Shaoyang, Yongzhou, and Loudi. Among these cases, most comprised farmers, with the age range mostly above 60 years. These characteristics are consistent with those reported by other scholars in China (8) and may be related to residents’ limited knowledge of rabies prevention in rural areas and their reduced ability to avoid animal attacks.

The cases were dominated by bites, followed by scratches, which is consistent with domestic studies (9). Among these, category III exposures accounted for 65.00%, which was considerably higher than that reported for wounds treated at canine outpatient clinics in China (10). The exposure sites were mainly the hands and the lower limbs, which may be related to the defensive posture adopted when attacked by animals (11). In terms of wound management, over 90% of the patients did not visit medical institutions for treatment. Similarly, more than 90% of the patients were not vaccinated, and among those with category III exposure, the proportion of patients not receiving passive immunization preparations exceeded 90%. These facts indicate that many people fail to fully recognize the danger of rabies and tend to take chances after exposure (12).

Among the factors influencing the incubation period, head and/or face exposure has a shorter incubation period than exposure at other parts of the body, mainly due to the neurophilic nature of the rabies virus and the abundance of peripheral nerve tissues in the head and face, allowing the virus to reach the central nervous system before vaccine-induced protective neutralizing antibodies are produced (13). Our study revealed that patients who sought medical treatment exhibited shorter incubation periods, which is consistent with previous research, likely because these cases were more severely exposed or had exposure to the head and/or face (14).

Currently, there is no universally accepted definition for rabies PEP failure. This study investigated the potential risks of PEP failure under different preventive interventions. Regardless of the reasons — such as inadequate understanding of PEP protocols, financial constraints, or personal negligence — patients who fail to receive all recommended preventive measures and subsequently develop rabies should be explicitly classified as PEP failure (5–6). Analysis of 22 PEP failure cases revealed that three cases with category III exposure received complete PEP in different levels of medical institutions. Nonetheless, their exposed areas were not entirely on the head or face. Thus, in the PEP process, it is necessary to increase the compliance of exposed individuals to participate in the entire process. Additionally, the risk of PEP failure in different situations must be considered (15).

This study has certain limitations. First, rabies patients often died during the investigation or cases were reported by family members, making it difficult to grasp the true and accurate exposure and disposal situation. This incomplete information may have affected the conclusions of this study. Second, while a preliminary analysis of factors influencing the incubation period was conducted, a more in-depth analysis is required. Third, some human rabies cases were clinically diagnosed because specimens were not collected immediately and no laboratory results were available.

In conclusion, the current situation of rabies prevention and control in Hunan Province remains a challenge. Comprehensive measures should be taken, such as adopting standardized dog management, strengthening control measures in high-risk areas, and improving public awareness of PEP, which may help reduce the incidence of rabies in Hunan.

HTML

Data Sources

Definitions

Statistical Analysis

Epidemiological Profile

Distribution of Disease

Characteristics of Animals Causing Exposure

Exposure and Wound Management

Post-exposure Prophylaxis

Incubation Period Analysis

Analysis of PEP Failure Cases

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: