-

Introduction: Gastrointestinal disease outbreaks pose significant public health challenges, particularly in high-density settings such as schools. This study presents a rare co-infection outbreak caused by two enteric viruses in a primary school.

Methods: Active case searching was employed to identify all cases, and pathogens were identified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) nucleic acid testing.

Results: The outbreak affected 14 cases in 1 class, yielding a 38.9% attack rate with mild symptoms. Among 8 anal swab samples, 3 cases tested positive for norovirus GI, 2 cases (including the index case) tested positive for rotavirus A, and 1 case tested positive for both norovirus GI and rotavirus A. Among 8 environmental samples, 4 samples tested positive for both norovirus GI and rotavirus A, 1 sample tested positive for norovirus GI only, and 3 samples tested positive for rotavirus A only. The outbreak was initiated by the index case vomiting in the classroom; individuals with atypical symptoms and environmental contamination subsequently contributed to the co-infection transmission. Case numbers peaked within 3 days before the outbreak was successfully controlled. Notably, family-based active case searching identified 1 asymptomatic carrier of norovirus GI. Dining facilities and water hygiene were confirmed safe, ruling out foodborne or waterborne transmission.

Conclusion: Timely and proactive intervention strategies are crucial for outbreak control in high-density settings, particularly given that different pathogens possess varying transmission potentials and incubation periods.

-

On March 20, 2025, the Pudong New Area CDC (Health Supervision Institute) received reports from the Community Health Service Center (CHSC) regarding clustered vomiting incidents among students in a single primary school class. In collaboration with the CHSC, the Pudong New Area CDC (Health Supervision) initiated an epidemiological investigation and intervention to determine the etiology, identify the potential infection source, and implement effective control strategies.

-

School characteristics: The outbreak occurred at a public primary school comprising 6 grades, 28 classes, 961 students, and 75 faculty members. The facility consisted of two three-story buildings (five classrooms per floor) with single-gender toilets equipped with hand-washing liquid on each floor (male toilets on the 1st and 3rd floors; female toilets on the 2nd floor). The affected class was centrally located on the 3rd floor of the north teaching building. Each classroom operated independently for instruction with mechanical fan ventilation. No collective activities had been organized at the school in the preceding weeks. Students and teachers consumed meals in their classrooms using steam-disinfected tableware. Kitchen staff had maintained good health status during the previous 2 weeks. Students used personal cups for drinking water from direct water dispensers, and sanitation records were complete and up to date.

Index case: The index case was a 7-year-old boy who vomited in the classroom at 17:00 on March 17, 2025. The vomitus was cleaned up approximately 5 minutes later using the emergency vomiting disposal kit. Student exposure duration varied as they were in the process of leaving the classroom. He vomited again at home but attended school on March 18–19 without seeking medical care and experienced no further vomiting or diarrhea. His condition remained stable with no chills or urgency, and he subsequently tested positive for rotavirus group A infection. He had no record of recent vaccinations, no history of consuming suspect food, no contact with suspected cases, and no recent travel. No similar symptoms were observed in his cohabiting parents.

Co-infection case: The co-infection case developed illness at 08:00 on March 19, 2025, following the onset of the index case. She was a close friend of the index case and sat in the same row. She had frequent close contact with multiple classmates and had not been vaccinated against rotavirus. She developed nausea, vomiting (4 episodes within 24 hours), and abdominal pain but reported no vomiting episodes at school. This case was inferred to be the primary source of norovirus transmission in this co-infection outbreak.

Case definition: Cases were defined according to the 2015 Norovirus Outbreak Investigation and Prevention Technical Guidelines (1) as school-affiliated individuals (March 14–March 27) experiencing ≥2 vomiting episodes or ≥3 diarrheal episodes within 24 hours. Cases were identified through systematic class-based searches, interviews with teachers and parents, review of absence records, and active family-based case-finding.

Laboratory testing: Samples were tested for norovirus, rotavirus, astrovirus, enteric adenovirus, and sapovirus using the BioGerm fluorescent PCR kit at Pudong CDC (Health Supervision).

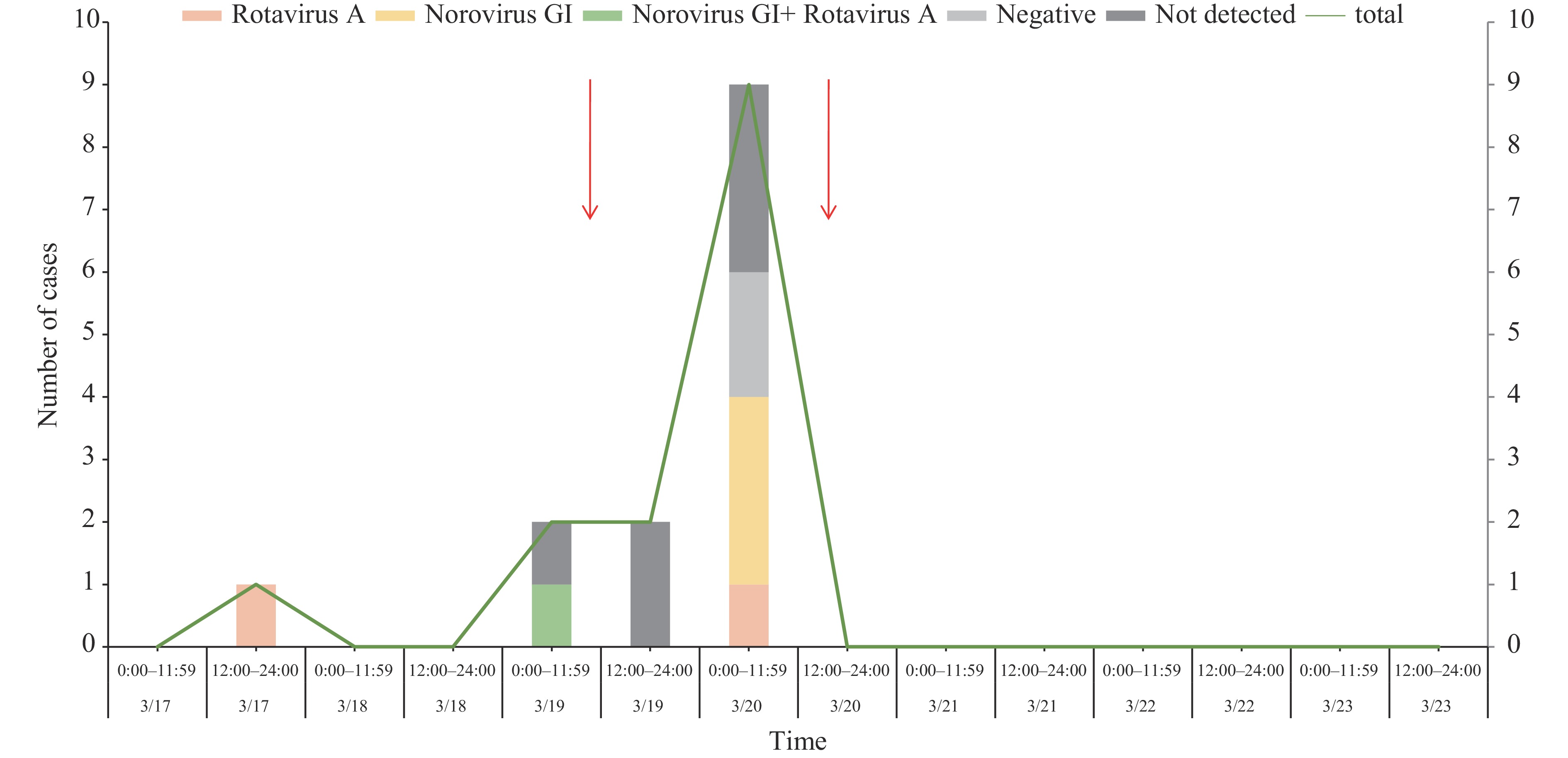

As of 15:00 on March 20, a total of 14 cases (6 male, 8 female; male-to-female ratio 0.75∶1) were confirmed exclusively in Class 4, Grade 2, yielding a 38.9% attack rate (14/36). Symptom onset spanned from March 17 (17:00) to March 20 (07:20), with the outbreak peaking on March 20 when 9 new cases emerged. The index case on March 17 accounted for 7.1% of cases, followed by 4 cases on March 19 (28.6%) and 9 cases on March 20 (64.3%) (Figure 1). All cases presented with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain with mild severity; notably, no cases reported diarrhea.

Because vomiting episodes occurred outside school hours, all secondary cases developed symptoms at home. Following on-site guidance from the CHSC, the school implemented several intervention strategies, and all cases with onset on March 19 and March 20 were excluded from school attendance the following day.

It is worth noting that 3 individuals in the affected class experienced atypical symptoms — only 1 vomiting episode within 24 hours — which did not meet the case definition and were therefore excluded from the outbreak count. These 3 individuals vomited in the classroom on March 18 or 19 but continued attending school in subsequent days.

Intervention measures were implemented on March 19 by CHSC and on March 20 by Pudong CDC (Health Supervision), as indicated by arrows in Figure 1. Each column in the figure represents clinical cases occurring within 12-hour intervals (x-axis) and the corresponding number of cases (y-axis).

On March 20, the Pudong CDC (Health Supervision) conducted an on-site investigation and collected 16 samples (8 anal swabs and 8 environmental samples) for testing. Laboratory analysis revealed that 3 cases tested positive for norovirus GI, 2 cases (including the index case) tested positive for rotavirus A, 1 case showed co-infection with both norovirus GI and rotavirus A, and 2 cases tested negative for all enteric viruses. The cycle threshold (CT) values of all fecal samples ranged from 33 to 34, indicating the late phase of viral shedding. All environmental samples tested positive for at least one pathogen listing 4 samples (desk 1, desk 2, classroom mop, and handwashing station) tested positive for both norovirus GI and rotavirus A; 1 sample (door handle 1) tested positive for norovirus GI only; and 3 samples (lectern, door handle 2, and classroom floor) tested positive for rotavirus A only.

Students infected solely with rotavirus A experienced 2 and 3 vomiting episodes, respectively, while those infected solely with norovirus GI experienced 4, 4, and 7 vomiting episodes. The co-infection case reported 4 vomiting episodes within 24 hours. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in symptom severity among the infection groups.

Further investigation revealed that 50% (18/36) of students in the affected class had received 1–3 doses of rotavirus vaccine. Among the 8 cases subjected to pathogen testing, 3 of the 4 unvaccinated students tested positive for rotavirus A. Notably, none of the 4 vaccinated students tested positive for rotavirus; they either tested positive for norovirus GI or negative for all enteric viruses.

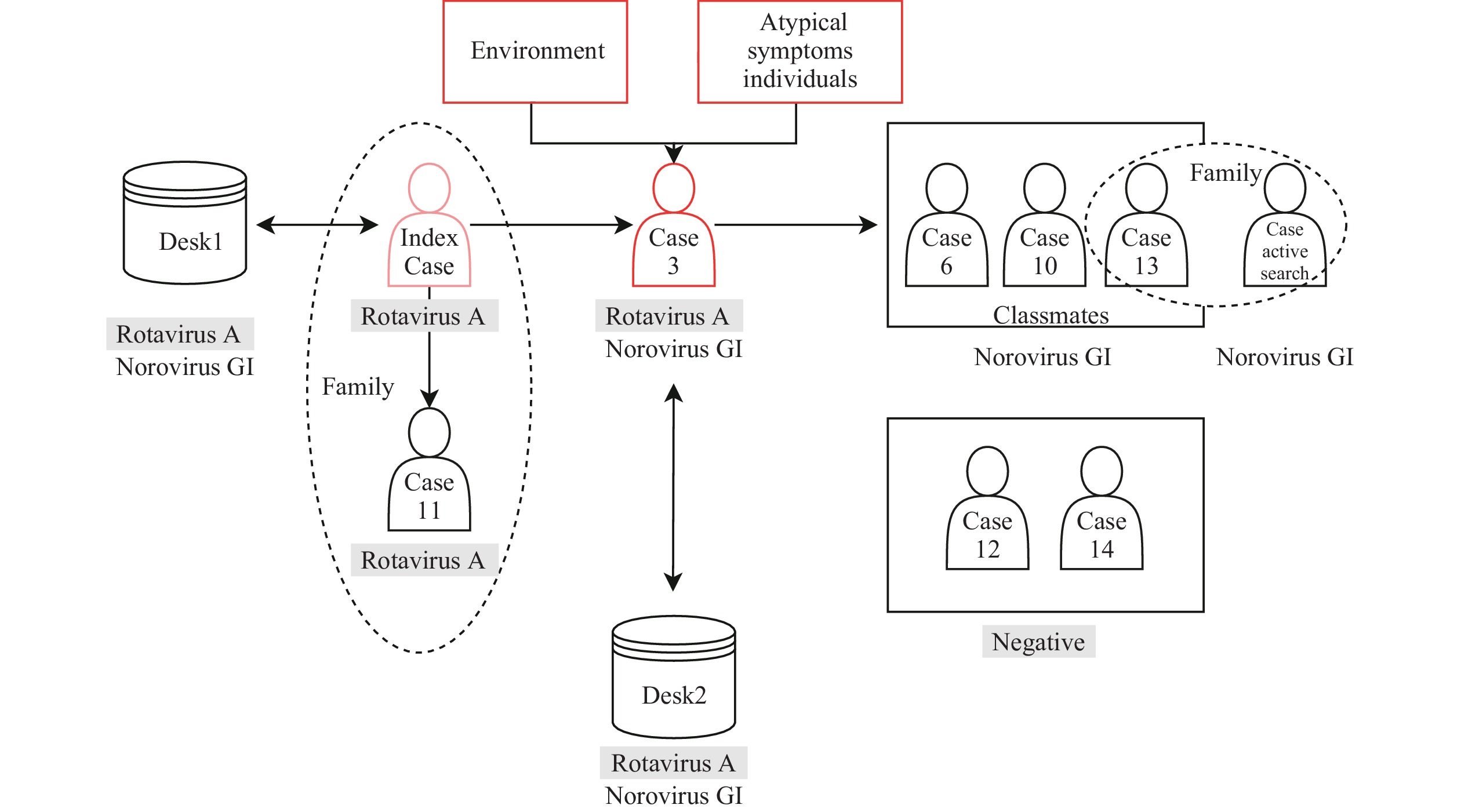

Detailed correlation analysis between cases and environmental contamination is presented in Figure 2. Case 3 represented the co-infection case. Additionally, family-based active case searching identified 1 asymptomatic carrier of norovirus GI — the younger brother of case 13. Although this individual was not included in the outbreak case count, the finding is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.Correlation between case distribution and environmental contamination during the outbreak.

Abbreviation: Norovirus GI=norovirus genogroup I; Rotavirus A=rotavirus genogroup A.Environmental investigation confirmed that the school’s dining facilities and water supply met safety standards. Given that only one class was affected, foodborne or waterborne transmission routes were excluded. However, cleaning and disinfection practices were found to be inadequate. The vomitus was cleaned up approximately 5 minutes after the incident using the emergency vomiting disposal kit. Disinfection personnel reported using a routine preventive disinfectant concentration of 500 mg/L, but the disinfectant solution preparation container lacked graduation markings, and disinfection records were incomplete.

-

The CHSC went to the school on March 19th and guided several intervention strategies including: enforcing strict environmental disinfection and proper handling of vomit; a strict 72-hour symptom-free return policy for patients; affected class isolation; suspending group activities; and promoting hand hygiene.

The Pudong CDC (Health Supervision) implemented comprehensive control measures on March 20, including: 1) Case & Contact Management: The affected class was relocated to an isolation classroom with staggered schedules. Participation in collective activities was prohibited, and mixing with other classes during after-school care was avoided. 2) Surveillance: School-based morning health checks and full-day observations were intensified, with immediate reporting of new cases. 3) Exclusion: Cases were required to isolate at home and could only return ≥72 hours after symptom resolution. 4) Environmental Disinfection: Strict disinfection protocols were enforced (classroom surfaces/corridors: 1,000 mg/L; bathrooms: 2,000 mg/L), mandating accurate measurement and record-keeping. 5) Activity Restrictions & Communication: Collective activities and shared classroom use were suspended. Parental notifications were issued promptly, and public communication was managed. 6) Health Promotion: Awareness of enteric infectious diseases and hand hygiene was actively promoted. 7) Coordination: Close communication was maintained with the CHSC and Pudong CDC (Health Supervision).

All secondary cases developed symptoms at home. By March 27, all affected individuals had fully recovered and returned to class, with no additional cases reported. Following complete implementation of all control measures, the outbreak was officially declared over.

-

According to data from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, norovirus has been responsible for 60%–96% of infectious diarrhea outbreaks nationally since 2012 (1). Despite this prevalence, epidemiological evidence documenting the co-transmission of norovirus and rotavirus remains scarce, particularly within high-density educational settings such as primary schools.

This primary school outbreak underscores both the risks and complexities of dual-pathogen transmission in crowded environments. Following the index case’s vomiting episode in the classroom, inadequate site disinfection and delayed evacuation of exposed students facilitated rotavirus transmission. Concurrently, norovirus — likely introduced through an asymptomatic carrier or pre-existing environmental contamination — amplified the outbreak’s scope. The high attack rate (38.9%) within a single classroom demonstrates the rapid transmission potential of these viruses in confined spaces, consistent with findings from previous studies (2-3). Four environmental samples tested positive for both pathogens, revealing persistent surface contamination on desks, handwashing stations, and classroom mops, thereby confirming fomite-mediated transmission — a phenomenon documented in other school-based outbreaks (4). Notably, rotavirus infections among primary school students are relatively uncommon, and such high co-detection rates in environmental samples have been rarely reported in the literature (3).

The hypothesis of a rotavirus–norovirus co-infection outbreak is supported by three key lines of evidence:

Laboratory confirmation: Half of all environmental samples yielded both viruses, with rotavirus detected in the index case’s anal swab and co-infection documented in an additional case.

Vaccination impact: Among the 8 symptomatic students tested, none of the rotavirus-vaccinated individuals developed rotavirus infection; these students either tested positive for norovirus alone or negative for both pathogens. While the small sample size limits generalizability, these findings are consistent with established vaccine efficacy against rotavirus in outbreak contexts.

Epidemiological concordance: Case numbers peaked 72 hours post-exposure, aligning with the known incubation periods of both viruses (norovirus: 1–2 days; rotavirus: 1–3 days).

These findings demonstrate that while norovirus dominates school outbreaks, rotavirus co-infections warrant careful consideration (5). Rotavirus is often transmitted in children under 5 years of age and is sensitive to disinfectants, with a relatively short environmental survival time (6). In contrast, norovirus affects all age groups and can spread through aerosols, exhibiting stronger transmissibility than rotavirus, a shorter incubation period, and prolonged environmental persistence (7). This study highlights the distinct transmission characteristics of these two viruses. When most students are vaccinated against rotavirus, the outbreak risk from rotavirus becomes lower than that from norovirus, underscoring the importance of identifying specific infectious pathogens to guide targeted control measures in future outbreak responses. Notably, rotavirus-infected cases in this outbreak exhibited milder symptoms (only 2–3 vomiting episodes) compared to typically reported presentations (severe diarrhea and dehydration), possibly due to partial vaccine-induced immunity. This observation further emphasizes the complexity of managing co-infections.

In China, rotavirus vaccination mainly includes Lanzhou lamb rotavirus (LLR), LLR3, and RotaTeq, which remains voluntary and primarily includes oral formulations. Coverage remains low due to cost (approximately $24/dose) and parental hesitancy; vaccination rates in Guangzhou (2009–2011) ranged from only 6.8% to 28.6% (8). By contrast, Shanghai — a high-income metropolis — achieved 41% RotaTeq coverage by 2021 (9), consistent with the 50.0% vaccination rate observed among students in the affected class during this outbreak. Significant urban-rural and inter-school disparities persist nationwide. Increasing vaccination coverage will require community subsidies, home-school health promotion campaigns, and enhanced parental education initiatives.

While RotaTeq demonstrates 79% efficacy against moderate-to-severe rotavirus gastroenteritis (9), its protective effect in co-infection scenarios remains understudied. China’s experience with rotavirus vaccination underscores the critical need for higher coverage rates and better integration with norovirus control strategies.

It is worth noting that 3 individuals with atypical symptoms in the affected class vomited only once within 24 hours on March 18 or 19 in the classroom and continued attending school, potentially playing an important role in sustaining the outbreak. Regrettably, samples were not collected from these individuals. Future outbreak responses should consider expanded active case finding and isolation management for individuals with atypical symptoms. Additionally, socially active individuals with co-infections deserve heightened attention due to their potential to amplify transmission.

This study has several limitations. First, testing gaps existed. Not all cases were tested, and asymptomatic carriers along with individuals presenting atypical symptoms remained untested, potentially leading to underestimation of the true attack rate. Second, the norovirus source could not be definitively established due to insufficient evidence, though asymptomatic shedding or environmental contamination are plausible explanations. Third, genotyping was not performed. Strain relatedness was not assessed, limiting insights into transmission chains, although the co-positivity of environmental and case samples strongly supported the co-infection hypothesis.

-

We thank the staff and students of the primary school for their cooperation during the investigation. We also acknowledge the support of the Pudong New Area Disease Prevention and Control Center (Health Supervision) and Heqing Community Health Service Center, and all other individuals involved in the management of this outbreak. We also thank Dr. Zhongjie Li from Peking Union Medical College for his suggestions for revising the manuscript.

-

Conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Pudong New Area Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Shanghai Pudong New Area Health Supervision Institute) (Approval No: PDCDCLL-20241024-001). Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to enrollment. All data were anonymized before analysis to protect participant confidentiality.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: