-

To address global public health security challenges and strengthen emergency preparedness, the international community has developed 13 assessment tools, spanning four major domains: national governance and health security preparedness, risk assessment and management, health system capacity and emergency response, and dynamic monitoring (Table 1). Among these instruments, the Global Health Security Index (GHSI), Joint External Evaluation (JEE), and State Party Annual Reporting tool (SPAR) have gained widespread adoption due to their comprehensive indicator frameworks and multi-tiered structures. The GHSI, developed through collaboration between the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Johns Hopkins University, evaluates epidemic response capabilities across 195 countries (1). In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the JEE, a collaborative process combining internal country self-assessment with external peer review by multidisciplinary expert teams to evaluate national capacities for preventing, detecting, and responding to health threats (2). The annual report survey questionnaire, in use since 2010, underwent revision in 2018 and was renamed SPAR. This tool monitors States Parties’ progress in implementing core capacities of the International Health Regulations (IHR) through annual self-assessment (3). However, because these three tools were designed based on historical pandemic experiences, they inadequately captured the unique complexities of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in flawed indicator design and inappropriate weight allocations. This limitation manifested in the paradoxical observation that countries ranking highly in pre-pandemic assessments often performed poorly in their actual pandemic responses (4–7). Although academic studies have evaluated individual aspects of these tools, comprehensive systematic reviews examining their collective performance during the pandemic remain scarce.

Tool Issuing

OrganizationRelease Time Indicator Changes Indicator

TypeScope of

ApplicationWorldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) World Bank 1996 Updated in 2025 Third-party review Assess governance quality and national stability Toolkit for Assessing Health-System Capacity for Crisis Management (THCCM) WHO Regional Office for Europe 2007 None Self-assessment Assess the crisis management capabilities of the healthcare system INFORM Global Risk Index JRC 2015 Transformation into INFORM COVID-19 Risk Third-party review Assess the risk of humanitarian crises and disasters in countries around the world Joint External Evaluation (JEE) WHO 2016 First update: 2018

Second update: 2021Self-assessment/peer review Assess the capabilities of the national public health security system Health Emergency Preparedness Self-Assessment Tool (HEPSA) ECDC 2018 None Self-assessment Self-assess the level and capability of health emergency preparedness IHR States Parties Self-Assessment Annual Report (SPAR) WHO 2018 Revised as SPAR in 2018, updated in 2021. Self-assessment Measuring a country’s public health preparedness and response capacity Global Health Security Index (GHSI) Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 2019 Updated in 2021 Third-party review Assessment of global health security preparedness by country Epidemic Preparedness Index (EPI) WEF 2019 None Third-party review Assess the country’s preparedness for responding to the pandemic INFORM COVID-19 Risk JRC 2020 Created after COVID-19 Third-party review Assess the risk of the pandemic and the country’s response capabilities COVID-19 Regional Safety Index (RASI) In-Depth Knowledge Think Tank 2020 Created after COVID-19 Third-party review Assess regional security and prevention capabilities during the pandemic COVID-19 Overall Government Response Index (CGRI) Oxford University Pandemic Policy Global Group 2022 Created after COVID-19 Third-party review Assess the strictness of various governments’ responses to the pandemic Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) WHO and World Bank 2023 Created after COVID-19 Third-party review/

Peer reviewAssessment of global health emergency preparedness and response capabilities WHO Dynamic Preparedness Metric (DPM) WHO, World Bank, and UNICEF 2024 Created after COVID-19 Third-party review Assess the country’s capacity to respond to public health emergencies Abbreviations: WHO=World Health Organization; JRC=European Union Joint Research Centre; ECDC=European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; WEF=World Economic Forum; UNICEF=United Nations Children’s Fund. Table 1. Overview of 13 global public health security relevant assessment tools.

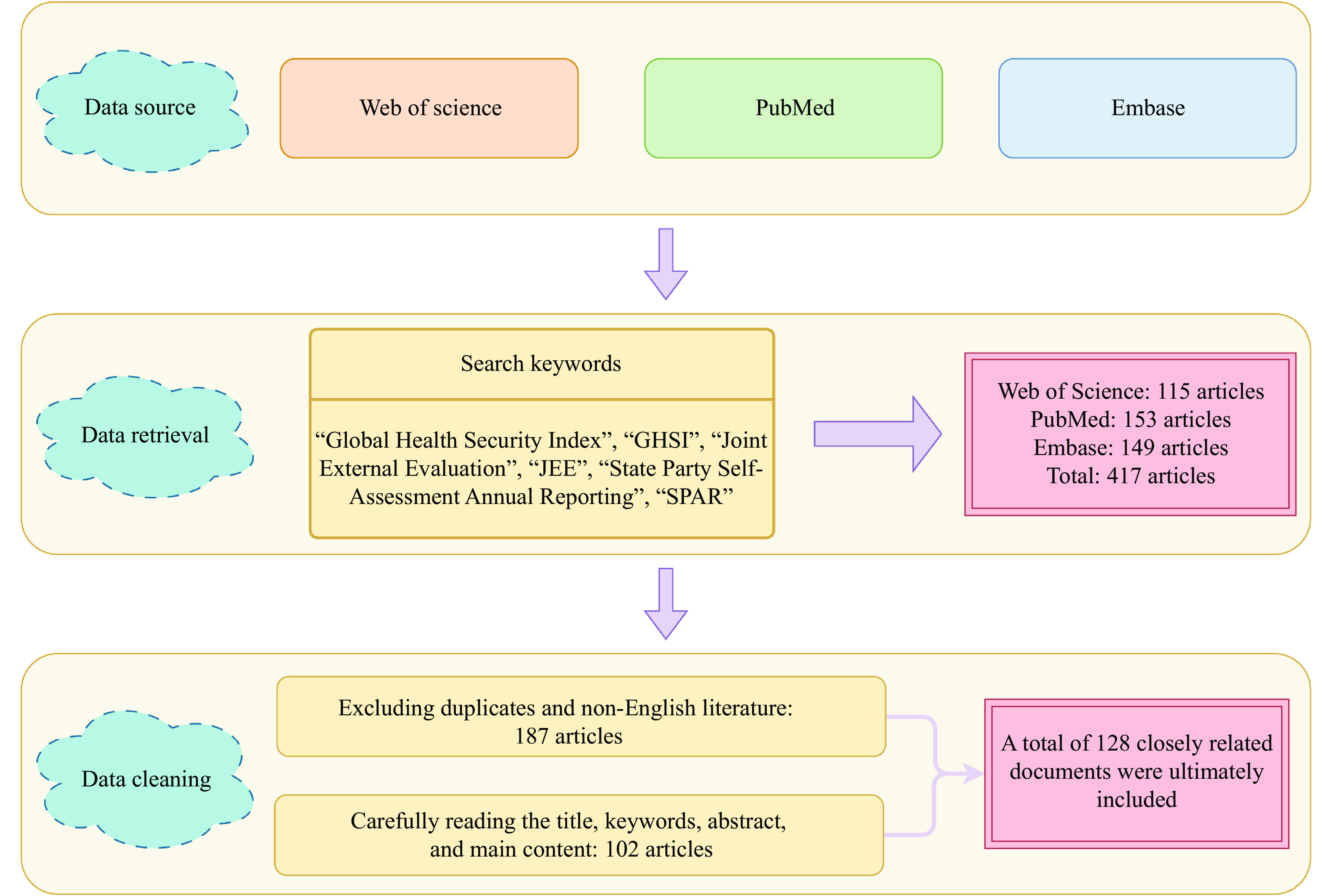

To address this gap, we conducted a systematic literature search of Web of Science, Embase, and PubMed databases for publications related to GHSI, JEE, and SPAR through August 30, 2025. The screening process is illustrated in Figure 1. Through critical analysis of this literature, we examined the performance of these tools during the pandemic, identified inherent structural flaws and factors contributing to their limited predictive validity, and evaluated post-pandemic indicator revisions. Our findings clarify future research priorities and provide evidence-based recommendations for enhancing global public health security assessment tools.

-

The SPAR mechanism faces a fundamental data integrity challenge. Although SPAR emphasizes transparency and government accountability, its dependence on self-reported data introduces systematic bias (8). The absence of robust verification mechanisms on online platforms creates opportunities for countries to inflate their ratings, whether to preserve international reputation or secure development funding (7,9). Paradoxically, when subjected to external JEE evaluations, some countries strategically deflate their self-assessment scores, further compromising data objectivity and reliability (3,10). Moreover, despite the World Health Assembly (WHA) requirements for timely SPAR report submission by contracting state parties, weak enforcement mechanisms have resulted in delayed reporting by numerous countries (9).

-

While the JEE employs peer review by expert groups and WHO authorization to ensure data authenticity and accountability, expert subjectivity remains a critical limitation. The JEE framework integrates external expert evaluation with internal self-assessment, yet the internal component remains vulnerable to subjective biases comparable to those affecting SPAR (11). Although external evaluations are conducted by independent expert teams following WHO training protocols, variations in evaluators’ professional backgrounds, indicator interpretation, and assessment approaches consistently diminish result reliability (12–13). Furthermore, the voluntary nature of JEE participation resulted in only 50% of States Parties completing assessments in 2021, substantially undermining both the universality of global health security evaluations and comprehensive data coverage (2).

-

Despite the transparency of GHSI indicator data, significant limitations constrain its utility. Data quality, completeness, and timeliness vary considerably across the 195 participating countries, directly affecting assessment scores. High-income countries typically maintain more accurate reporting systems, creating systematic assessment biases across development levels (1,14). Delays in public data updates further restrict effective data collection (1). Although the GHSI methodology demonstrates greater rigor than JEE and SPAR approaches, its heavy reliance on publicly available information creates particular challenges. In low- and middle-income countries, pandemic preparedness and policy documents frequently remain undisclosed or incompletely published, complicating data collection and systematically depressing scores for affected nations (15–16). Low-income regions, particularly in Africa, face technological and resource constraints that compound data acquisition difficulties (17). Additionally, the absence of standardized global data frameworks has substantially increased the complexity of obtaining consistent, comparable data across countries (18).

-

Improper allocation of indicator weights substantially compromises the accuracy of assessment outcomes. The GHSI applies uniform weighting (0.167) across all categories, failing to capture the varying importance of different indicators for public health security (16,19). Chang CL and colleagues demonstrated that Detection and Reporting carries the greatest weight in determining overall preparedness (20). Similarly, Abroon Q et al., employing a Bayesian network model, identified Emergency Preparedness and Response Planning as the most influential factor in GHSI scoring (21).

Both JEE and SPAR employ a five-level color-coded system to qualitatively assess capability levels across indicators, then aggregate these ratings into total scores (22–23). Under SPAR compilation rules, for example, if indicator 2.1 achieves level 3 and indicator 2.2 reaches level 4, the composite percentage for indicator 2 equals [(3/5 × 100) + (4/5 × 100)] / 2 = 70%. This equal-weighting approach inadequately reflects the differential contributions of individual capabilities to overall preparedness (24).

-

By design, GHSI, JEE, and SPAR function as cross-sectional assessment tools rather than predictive instruments, capturing a country’s health security capabilities at a single point in time (25–26). This static nature fundamentally limits their ability to track the dynamic progression of epidemics, where virus transmission patterns and response measures evolve continuously, rendering real-time indicator updates challenging (12). A more critical limitation stems from the indicator systems’ narrow emphasis on technical capabilities and health infrastructure, which fails to adequately incorporate broader public value dimensions including socio-political contexts, governance structures, and cultural factors that shape pandemic responses (14,27–29). Supporting this observation, research by David BD and colleagues demonstrates that the correlation between GHSI/SPAR scores and COVID-19 outcomes weakens progressively over time, as non-technical factors such as social behavior patterns and public trust in government institutions assume greater importance during later pandemic stages (30).

-

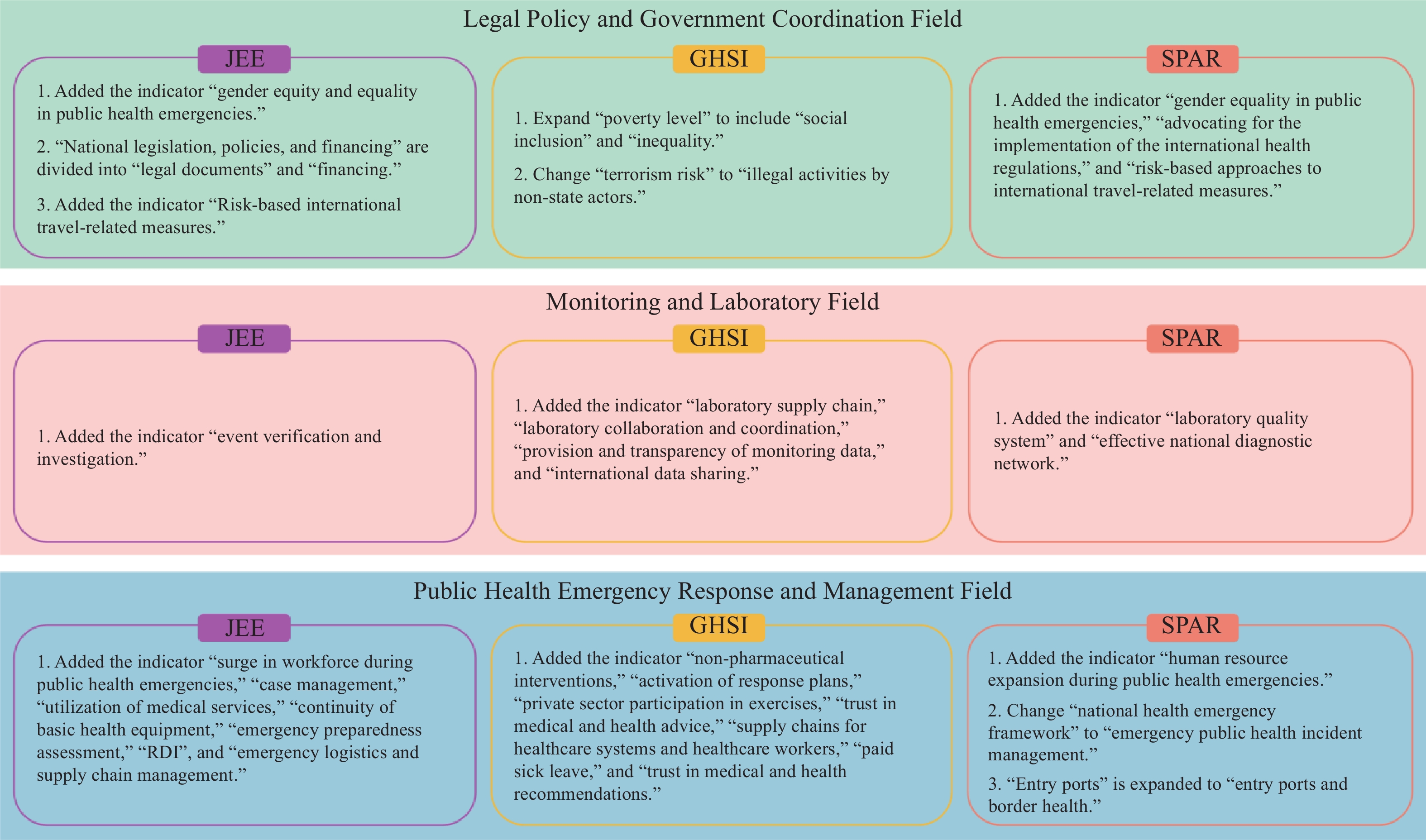

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the organizations responsible for JEE, GHSI, and SPAR undertook comprehensive revisions of their assessment frameworks. Our review of the third edition of JEE, the 2021 edition of GHSI, and the second edition of SPAR identified key indicators that were added, modified, or removed across multiple technical domains. The most substantial revisions occurred in three critical areas: legal policy and government coordination, surveillance and laboratory capacity building, and emergency response and management. Figure 2 illustrates the additions, updates, and deletions of tertiary indicators across these three technical fields.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.Addition, deletion, and updating of tertiary indicators in three global public health security relevant assessment tools.

Abbreviations: GHSI=Global Health Security Index; JEE=Joint External Evaluation; SPAR=States Parties Self-Assessment Annual Report; RDI=research, development, and innovation.The newly introduced indicators in legal policies and government coordination address two previously underrepresented dimensions: gender equity in public health emergencies and international risk management metrics. The pandemic exposed significant gaps in women’s health protection, particularly given that women constitute a substantial proportion of the healthcare workforce and consequently faced elevated infection risks during epidemic prevention and control phases. Despite this vulnerability, governments historically neglected gender-disaggregated data collection, failed to recognize women’s unique status in emergency response, and lacked targeted protective measures (31). Additionally, the revised indicators incorporate terrorism risk assessment, recognizing its intersection with international travel restrictions and epidemic prevention efforts. Evidence from the early stages of COVID-19 demonstrated that restrictions on international travel and public gatherings were among the most effective containment measures (32–33).

The updated indicators in surveillance and laboratory capacity building encompass laboratory testing efficiency, diagnostic reliability, and rapid response capability. During the COVID-19 pandemic, rapid testing and case isolation proved essential for viral containment and for identifying optimal intervention windows. However, global laboratory testing capacity failed to meet escalating demands, highlighting critical infrastructure gaps (34). Ecuador’s experience illustrates this challenge: insufficient testing capacity caused the country to miss the optimal prevention and control window, resulting in incomplete surveillance data on COVID-19 infections and mortality rates (35). The newly added indicators for data transparency and international data sharing reflect the health surveillance community’s growing recognition that open data exchange is fundamental to effective emergency response. Timely and accurate data sharing enhances the precision of dynamic epidemiological reporting, such as infection counts in heavily affected regions, thereby reducing errors in government decision-making (36–37).

The field of public health emergency response and management encompasses human resource reserves, logistical support, case investigation, contact tracing, and non-pharmaceutical interventions, all aimed at building an efficient, multi-departmental collaborative emergency system. During the pandemic, Italy enhanced flexibility in resource allocation and continuity of medical services through multi-departmental human resource distribution and cross-training, which became a key factor in responding to the pandemic and future disasters (38). China and South Korea ensure the supply of medical human resources through strict administrative procedures and on-the-job training (39–40). Additionally, countries such as China and Chile have effectively curbed the spread of the epidemic by combining non-pharmaceutical interventions with vaccination (41–42).

-

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations responsible for the three types of assessment tools expanded and refined their indicators based on experience; however, these revisions have not fully addressed the fundamental issue of low evaluation effectiveness. To meet global health security challenges in the post-pandemic era, future assessment tools should focus on improving: 1) expanding data sources and improving data accessibility for low- and middle-income countries. Utilize independent public health expert teams from various institutions and countries to conduct multiple rounds of verification and validation on publicly available and self-reported data, enhancing the overall quality of the data; 2) the indicator system and weight allocation by comprehensively incorporating factors such as policy implementation, historical culture, socioeconomics, public trust, community engagement, and environmental ecology, while reasonably adjusting weights to reflect their relative importance in different contexts; 3) overcoming the limitations of existing global public health security assessment tools that focus on static evaluation by developing a dynamic risk monitoring and assessment system. The core foundation of this goal lies in ensuring the accuracy, timeliness, and comprehensiveness of data input, which can be efficiently obtained and preprocessed using methods such as machine learning and geographic information systems (GIS). Building on this, system modeling approaches like dynamic Bayesian networks, complex network analysis, and spatiotemporal epidemiological models can effectively integrate this dynamic information to construct a dynamic risk assessment and monitoring system, thereby enhancing the sensitivity and precision of early warning and response (43–44).

HTML

Data Authenticity and Accessibility

SPAR self-reporting limitations:

JEE expert-driven model constraints:

GHSI public data dependency issues:

Indicator Weight Allocation

The Static Characteristics of Indicator Design

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: