-

Introduction: Disability-free life expectancy (DFLE) is a key metric of healthy aging. While prior studies have explored its trends and provincial-level patterns, sub-provincial variations and urban-rural disparities in China are underexplored.

Methods: DFLE across prefectures was estimated using the Sullivan method, based on mortality data from the death registration system and disability data from the National Health Service Survey. A geodetector was used to assess the explanatory power of the socioeconomic, healthcare, environmental, and demographic factors.

Results: DFLE increased in all regions between 2018 and 2023, with a narrowing urban-rural gap. The largest gains occurred in the western region, but urban–rural inequality showed the least improvement. DFLE exhibited notable stratified spatial heterogeneity, predominantly driven by socioeconomic factors, whose influence weakened with advancing age, whereas environmental and demographic factors became more prominent. All the factors had stronger explanatory power in rural areas.

Conclusion: Although DFLE improved nationwide, inequalities persisted. Targeted public health strategies are needed to reduce disparities, with priority placed on healthcare access, social security, and climate-adaptive infrastructure in rural areas, particularly in western China.

-

In recent years, the life expectancy (LE) in China has continued to increase, reaching 79 years by 2024 (1). With the increase in LE, growing emphasis has been placed on quality of life. In the context of accelerated population aging, disability-free life expectancy (DFLE) among older adults has become a crucial indicator of the overall health of a society. In this study, DFLE was defined as the number of years an individual was expected to live without disability as measured by Activities of Daily Living (ADL). Previous studies have shown that DFLE among older adults has a steady upward trend; however, significant disparities persist across provinces and between genders (2-3). However, due to limitations in data availability, research on sub-provincial patterns and urban–rural differences remains limited.

Considering the disparities in health risks between geographic areas, especially between urban and rural areas, the spatial distribution and temporal trends of DFLE and the types, strengths, and age-specific effects of its determinants are likely to vary significantly. A comparative analysis of DFLE’s spatiotemporal patterns and determinants among older adults in urban and rural areas can help elucidate the mechanisms underlying spatial health inequalities and support the development of tailored health interventions aimed at narrowing regional and urban–rural health gaps.

To address the gaps in existing research, this study analyzed the DFLE of Chinese adults aged 60 and above in 2018 and 2023, focusing on its spatiotemporal variations and urban–rural disparities and further identified the determinants underlying these differences.

Mortality data were obtained from the Center for Health Statistics and Information of the National Health Commission. Deaths were categorized into 19 age groups: <1 year, 1–4, 5–9, …, 80–84, and 85 years and above. Age-specific population counts were derived from the Sixth and Seventh National Population Censuses, with data for other years estimated through linear interpolation and extrapolation between the two census points. Data on ADL were obtained from the National Health Service Survey, which employed a multistage, stratified, cluster random sampling strategy. In the first stage, the country was divided into eastern urban, eastern rural, central urban, central rural, western urban, and western rural. From each stratum, 26 counties or districts were randomly selected, yielding 156 sample units. Then, five townships or subdistricts were randomly selected from each sampled county. Subsequently, two villages or neighborhood committees were randomly chosen within each township or subdistrict. Finally, 60 households were systematically sampled from each selected village or neighborhood committee (4).

Urban areas were defined as municipalities and prefecture-level municipal districts, whereas rural areas were defined as counties and county-level cities. The ADL questionnaire consisted of six items: dressing, eating, bathing, getting in and out of bed, using the toilet, and controlling bowel and bladder functions. The proportion of individuals who reported no difficulty with all six tasks at each survey site was calculated and used as an age-specific health status indicator.

Based on previous literature and data availability, this study incorporated determinants from four domains: environment, socioeconomic level, healthcare resources, and demographic characteristics. For environmental factors, annual average temperature, total annual precipitation, average annual particulate matter (PM) 2.5 concentration, and normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) were included. Socioeconomic indicators included per capita disposable income, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and proportion of educational expenditure (share of government education spending in the local public budget). Healthcare resources were measured as the number of physicians per thousand people. Regarding demographic characteristics, old-age dependency ratio was used as a key indicator. Environmental data were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environment Data Center (http://data.tpdc.ac.cn). Data for the other influencing factors were sourced from statistical yearbooks and population censuses.

The Geodetector method was employed to quantify the explanatory power of various determinants of spatial disparities in the DFLE. The core assumption of this method is that, if an independent variable significantly affects a dependent variable, their spatial distributions should exhibit similarity (5-6). By stratifying each determinant in a way that minimized the within-group variance and maximized the between-group variance of DFLE, the method assessed the explanatory power of each factor. This explanatory power was quantified using the q-statistic as follows:

$$ q=1-\frac{SSW}{SST}=\left(1-\frac{{\sum }_{h=1}^{L}{N}_{h}{\sigma }_{h}^{2}}{N{\sigma }^{2}}\right)\times 100\mathrm{\%} $$ where h=1, …, L denotes the strata or categories of the dependent variable Y or the explanatory variable X;

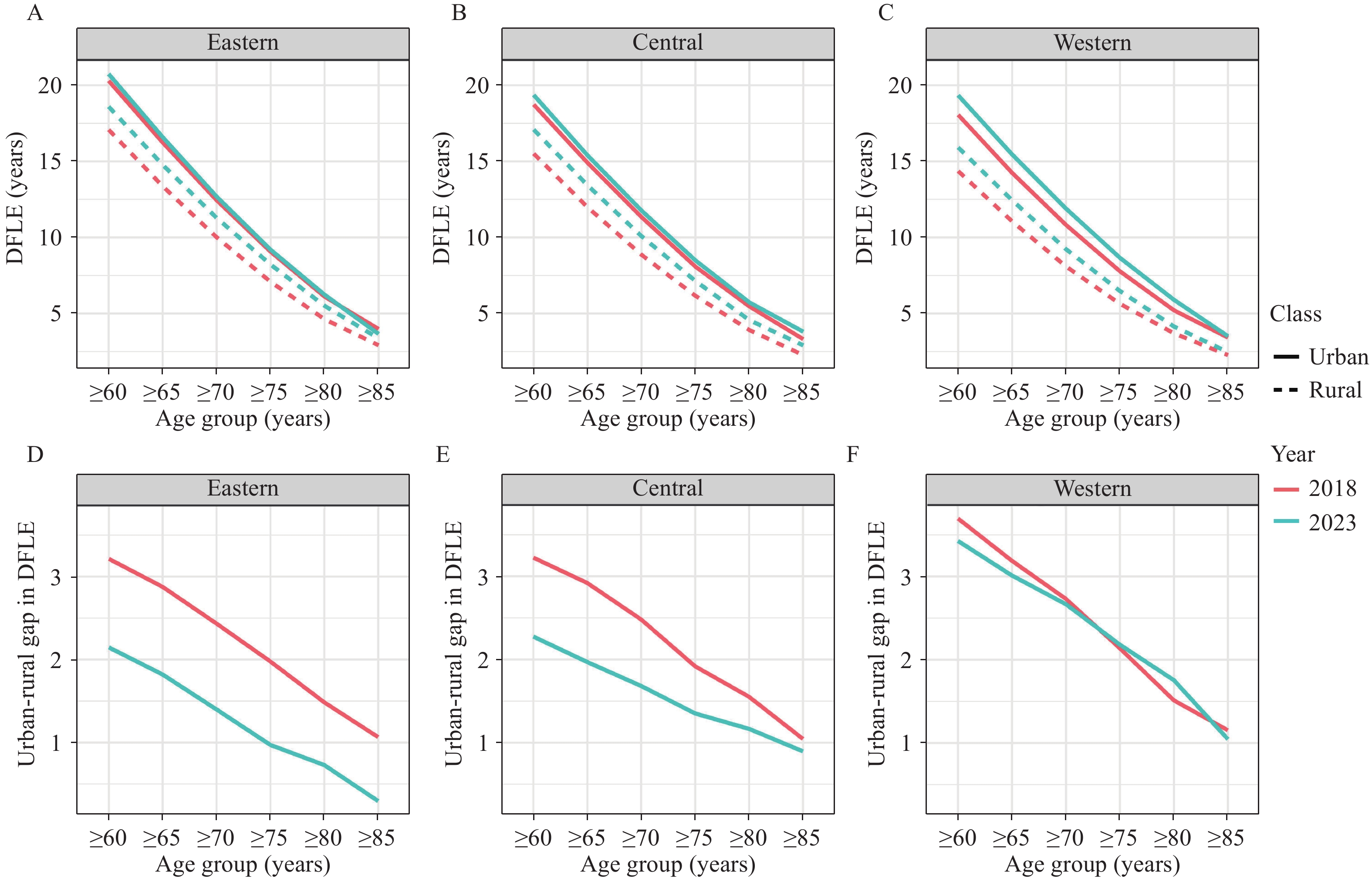

$ {\sigma }_{h}^{2} $ and$ {\sigma }^{2} $ represent the number of units in stratum h and in the entire study area, respectively. The sum of squares within strata (SSW) indicates the total within-group variance, whereas the total sum of squares (SST) represents the total variance across the study area. The q-statistic ranges from 0 to 1, reflecting the strength of spatial heterogeneity or the degree of association between the dependent and stratified explanatory variables. A higher q value implies a greater explanatory power of the factor over the spatial distribution of the dependent variable. All statistical analyses were performed using the R (version 4.3.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).Between 2018 and 2023, the age-specific DFLE at the age of 60 increased across urban and rural areas in the eastern, central, and western regions of China (Figure 1). However, the magnitude of this increase diminished with advancing age. DFLE was highest in the eastern region, followed by the central and western regions, and was consistently higher in urban areas than in rural areas (Figure 2). The absolute increase in DFLE was greater in rural areas than in urban areas, with the most significant DFLE gains observed in western urban centers (1.28 years) and central rural regions (1.58 years).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.DFLE and its urban-rural gaps by age group in eastern, central, and western China, 2018 and 2023. (A–C) DFLE in eastern, central, and western China; (D–F) corresponding urban–rural gaps.

Abbreviation: DFLE=disability-free life expectancy. Figure 2.

Figure 2.Spatial distribution of DFLE at age 60 in urban and rural areas of China, 2018 and 2023. (A) Urban areas in 2018; (B) rural areas in 2018; (C) urban areas in 2023; (D) rural areas in 2023.

Map approval number: GS京(2025) 1982号.

Abbreviation: DFLE=Disability-free life expectancy.

The urban–rural DFLE gap exhibited an east-to-west gradient, with the largest gap observed in the western region in 2018 (3.69 years), followed by the central (3.22 years) and eastern (3.21 years) regions. By 2023, the gap had narrowed in all 3 regions, with the most significant reduction seen in the east (down to 2.15 years), followed by the central region (2.27 years), while the gap in the west remained the largest (3.43 years). The urban–rural DFLE gap decreased progressively as age increased. Compared to the eastern and central regions, the urban–rural gap in the DFLE in the western region showed low levels of improvement between 2018 and 2023, with a notable widening in the 70–79 age group.

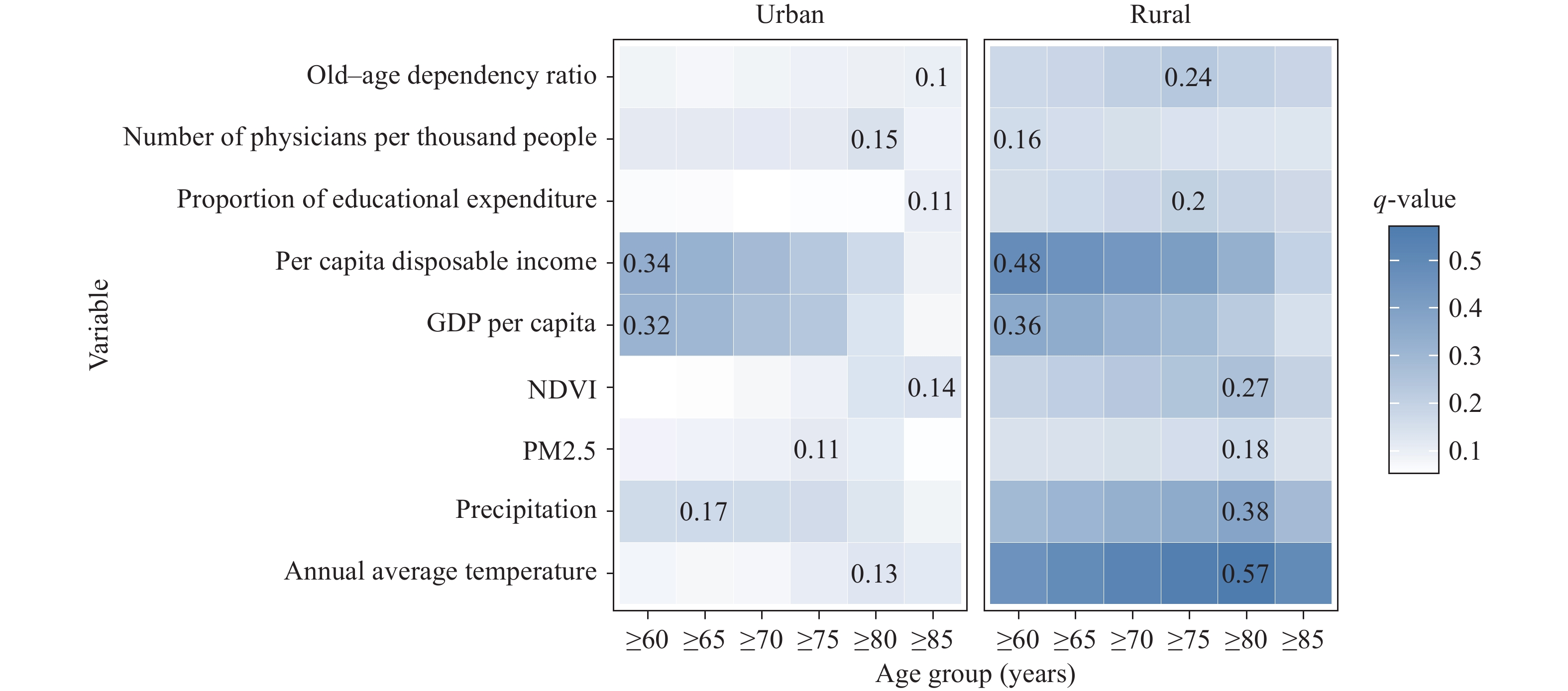

Figure 3 displays the q-values for all the examined determinants. Socioeconomic, healthcare, environmental, and demographic determinants significantly influenced the DFLE in urban and rural areas. In urban areas, socioeconomic indicators were the dominant contributors to DFLE disparities among those aged 60 and above, with disposable income per person (q=0.34) and GDP per capita (q=0.32) showing the highest influence. Among non-socioeconomic variables, precipitation and the number of physicians per thousand people showed the highest explanatory power, with q-values of 0.16 and 0.11, respectively. Similarly, the socioeconomic variables were predominant in rural areas, with per-person disposable income (q=0.48) and GDP per capita (q=0.36) showing the strongest correlations. Among the environmental determinants, the annual average temperature (q=0.46) and total annual precipitation (q=0.29) displayed the highest q-values, placing them immediately after socioeconomic factors.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.Age-specific q-values of determinants for DFLE in urban and rural areas.

Note: Numerical labels indicate the age group with the highest q-value for each determinant and its corresponding q-value. Abbreviation: GDP=Gross domestic product; NDVI=Normalized difference vegetation index; PM=Particulate matter; DFLE=Disability-free life expectancy.Compared with urban areas, all determinants demonstrated stronger explanatory power in rural areas. Although the q-values of most determinants declined or showed little change with increasing age, the q-values for NDVI and PM2.5 in urban regions, average annual temperature, total annual precipitation, NDVI, and the old-age dependency ratio in rural regions increased steadily.

-

In this study, the DFLE in the urban and rural regions of China for 2018 and 2023 was calculated and its temporal dynamics and spatial distribution were analyzed. Additionally, age-specific differences in the influence of socioeconomic, healthcare, environmental, and demographic determinants of DFLE between urban and rural areas were examined. The findings revealed significant spatial heterogeneity in DFLE, characterized by a gradient rising from west to east, and consistently higher DFLE in urban areas than in rural regions. The DFLE increased between 2018 and 2023, and the urban-rural gap in DFLE narrowed across all regions.

For those aged 60 and above, rural areas showed greater DFLE increases than urban areas, particularly in the western urban and central rural areas. However, despite the overall positive trend, the DFLE gap in the western region remained relatively wide and showed limited improvement. In some age groups, the urban-rural gap increased slightly. Compared with the eastern regions, western rural areas often face more constraints, including lower levels of medical insurance coverage, inadequate health service capacity, and underinvestment in age-friendly infrastructure. Additionally, older adults in western rural areas are more frequently exposed to challenging natural environments (7). These issues limit the effectiveness of public health interventions, particularly for older adults living in remote resource-constrained settings. These disparities may explain why the DFLE gains in western rural areas lag, particularly in older age groups.

Spatial heterogeneity in DFLE reflects the interplay between various determinants, predominantly socioeconomic factors. Furthermore, the influence and age-specific patterns of these determinants vary between urban and rural areas. Socioeconomic determinants are key drivers of spatial heterogeneity in DFLE (8). They influence health through multiple pathways by directly affecting living standards and correlating with access to health resources, lifestyle choices, and health-related behavioral patterns (9). Higher income, better education, and greater availability of medical resources are generally associated with a longer DFLE. In contrast, rural regions often face challenges, such as limited health and social services, higher old-age dependency, and greater exposure to environmental stressors, which may contribute to lower DFLE and wider geographic disparities (10-11).

The influence of socioeconomic factors on DFLE was also found to decline with increasing age, whereas environmental and demographic factors became more important in the oldest groups. This is primarily because, as people age, biological and physiological factors become more dominant in influencing health, while the impact of socioeconomic status, along with associated health behaviors and resources, gradually weakens (12). Simultaneously, older populations are more physiologically vulnerable to environmental stress and more dependent on family and community support (13).

This study’s authors recommend continued monitoring of DFLE across different regions and population groups to promote elderly health and reduce urban-rural and regional disparities. Policy efforts should prioritize improving the accessibility and quality of healthcare services in remote areas; expanding social security and long-term care programs tailored to rural elderly populations; and investing in climate-adaptive infrastructure, transportation networks, and community-based elderly care facilities. Supporting localized health workforce development may further strengthen service delivery in under-resourced settings. These comprehensive and regionally tailored strategies are essential for narrowing DFLE gaps and achieving equitable healthy aging nationwide.

This study had the following limitations. First, as all environmental variables (e.g., temperature, precipitation, PM2.5, and NDVI) were measured as annual averages, they may not reflect the sudden health effects of short-term extreme events in older adults. Second, the use of linear interpolation between the sixth and seventh national censuses to estimate age-specific population figures may fail to capture year-to-year variation.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: