-

Introduction: Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, causes chikungunya fever. Since its 2005 re-emergence, it has become endemic in 119 countries across Africa, Asia, the Americas, Europe, and Oceania. An outbreak in China’s Guangdong Province (July 2025) led to more than 15,000 cases by August 20, straining public health systems and highlighting the need to strengthen viral mutation surveillance. However, the precise genomic characteristics of this prevalent virus remain unknown, and this study aims to fill this critical knowledge gap through high-throughput sequencing technology.

Methods: This study collected two serum samples from this epidemic, extracting and sequencing total nucleic acids via an MGISEQ-G99 sequencer. Complete viral genomes were generated via a consensus reference assembly; they were phylogenetically analyzed and comparatively assessed to identify viral nucleotide variations and protein amino acid substitutions.

Results: Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that both research strains belong to the East/Central/South African genotype, clustering within the Middle African Lineage and sharing the highest identity with currently circulating CHIKV isolates from Réunion Island. The circulating strain carries adaptive mutation sites such as E1-A226V, E2-L210Q, and E2-I211T, significantly enhancing viral replication efficiency in Ae. albopictus.

Conclusions: Understanding viral etiology is essential for controlling outbreaks. The current epidemic strain carries mutations adaptive to Ae. albopictus, increasing transmission risk. Guangdong’s mosquito population — predominantly Ae. albopictus with limited Ae. aegypti presence — facilitates efficient virus import and spread.

-

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the genus Alphavirus of the family Togaviridae. As a significant mosquito-borne pathogen, CHIKV has spread to nearly all regions inhabited by Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, facilitated by increasing international travel (1). According to statistics from the World Health Organization, since the re-emergence of chikungunya fever in 2005, the virus has become endemic in 119 countries, affecting regions across Africa, Asia, islands in the Indian Ocean, the South Pacific islands, Europe, and the Americas (2).

The CHIKV genome is approximately 11,800 bases in length and consists of a 5’ untranslated region (5’ UTR), two open reading frames, and a 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR). The two open reading frames encode two polyprotein precursors (CHIKVgp1 and CHIKVgp2). CHIKVgp1 is cleaved by the viral protease nsP2 into four nonstructural proteins (nsP1–nsP4), whereas host cell proteases process CHIKVgp2 into five structural proteins — the capsid protein (C), envelope glycoproteins (E1 and E2), and E3 and 6K proteins — which are involved in viral assembly and budding (3). During viral infection, the E2 protein serves as the primary target for neutralizing antibodies (4). The 3’ UTR is a length polymorphism and contains functional RNA secondary structures (e.g., the stem-loop Y structure and repeated sequence elements), which play critical roles in host adaptation and viral replication (5).

Phylogenetic analysis of E1 gene sequences classified CHIKV into three genotypes: West African, Asian, and East/Central/South African (ECSA) (6). The re-emergence of CHIKV in Kenya in 2004 and its subsequent outbreak on Réunion Island in 2005 marked the emergence of the ECSA genotype as the dominant circulating lineage, during which adaptive mutations accumulated. Virological data indicate that the A226V substitution in the E1 envelope glycoprotein enhances CHIKV replication titers in Aedes mosquitoes, thereby increasing the transmission capacity of the mutant virus (7). The E2-L210Q and E2-I211T substitutions represent adaptive mutations that synergistically increase CHIKV transmission efficiency in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes. While E2-I211T (acquired circa 2004–2005) establishes a genetic background permissive for mosquito adaptation, E2-L210Q specifically augments midgut infectivity and viral dissemination, with both mutations exhibiting epistatic interactions with the key E1-A226V substitution (8). Since their initial detection in 2010, two novel mutations (E1-K211E and E2-V264A) have exhibited distinct genotypic distributions: E1-K211E is exclusively found in Asian lineages, whereas E2-V264A represents a unique cross-genotypic substitution. Functional studies have confirmed that the double mutant (E1-K211E + E2-V264A) in the background of E1-226A confers significantly enhanced transmission efficiency in Ae. aegypti (9).

Viral genomic surveillance activities have been driven by the rapid development of DNA sequencing technology and bioinformatics tools for genomic data analysis. These tools have allowed characterization of the genome and dispersal patterns of emerging and re-emerging pathogens. The 2025 large-scale Chikungunya fever outbreak in Shunde District, Foshan City, Guangdong Province, China, has drawn widespread attention (10). The release of the current epidemic strain’s full genomic sequence and identification of critical mutation sites are essential for effective outbreak containment. Based on this knowledge gap, the present study aims to decode and obtain the complete genomic sequence of the circulating strain, enabling public health personnel to understand the genetic evolution and characteristics of the virus, thereby facilitating timely adjustments to control strategies.

On July 26, 2025, chikungunya virus infection was confirmed in two tourists who had entered Shenzhen from other Guangdong cities. This study immediately extracted nucleic acids from the samples and conducted meta-transcriptomic sequencing for molecular tracing of the viral origin. During the sequence assembly process, the La Réunion outbreak strain, UVE/CHIKV/2024/RE/CNR_79903 (GenBank: PV593524), was selected as the reference genome based on the optimal results from average nucleotide identity analysis. The 2 assembled viral genomes, designated GM01_ycj0728 and GM02_yzc0728, each comprised 11,713 bp with >99.7% coverage at a 30× sequencing depth.

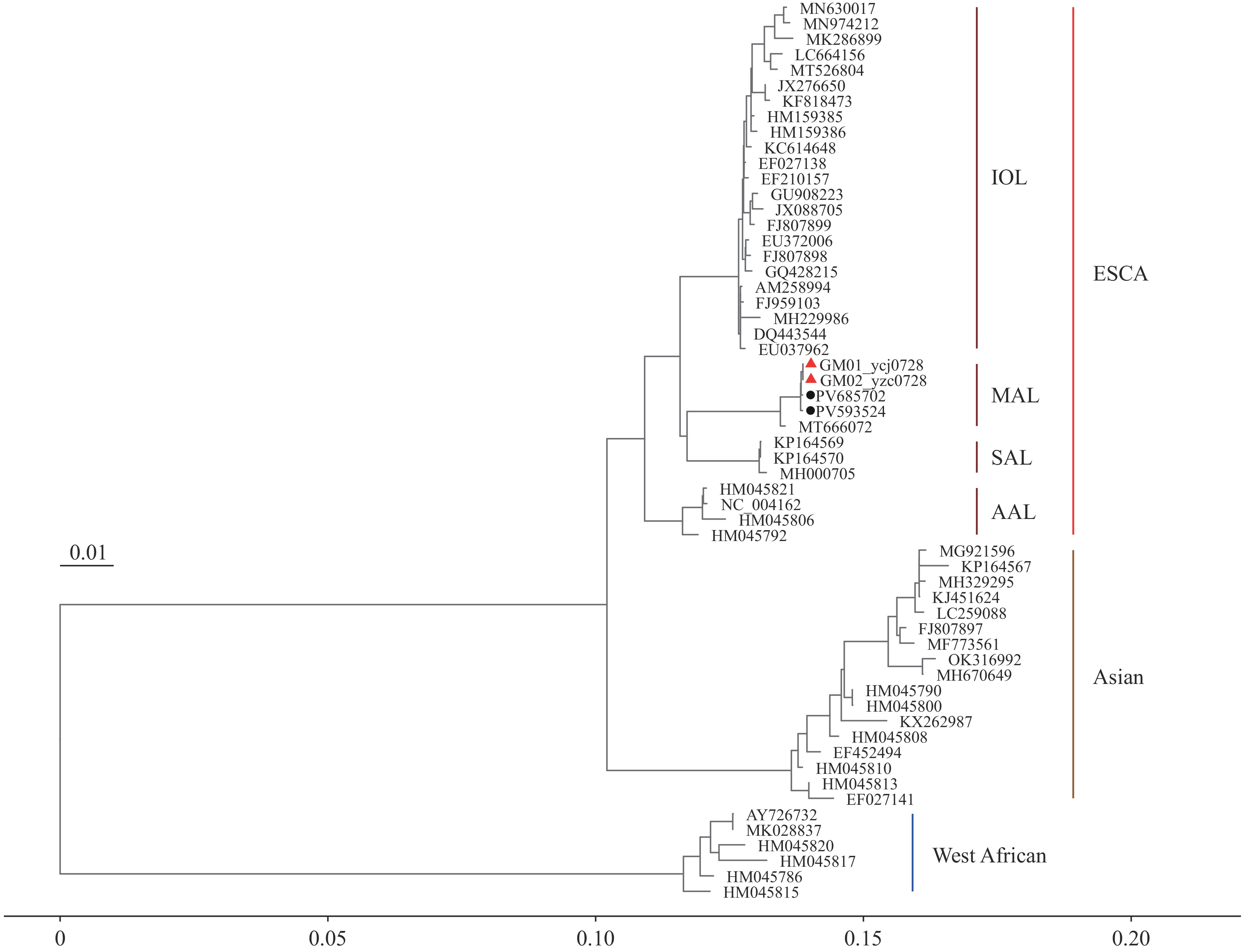

Multiple sequence alignment and maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analyses (substitution model: GTR+F+I+G4; 1,000 bootstrap replicates) demonstrated that both strains clustered most closely with the UVE/CHIKV/2024/RE/CNR_79903 (GenBank: PV593524) and S30b03 (GenBank: PV685702) isolates from La Réunion (2024–2025). Together with the CAM/2016/Yaounde strain from Cameroon (GenBank: MT666072; sampled in 2021), these viruses were phylogenetically classified within the Central African lineage (Figure 1). Genomic comparison between the two viral strains analyzed in this study revealed no single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis of Chikungunya virus based on whole-genome nucleotide sequences.

Note: The tree was inferred with IQ-TREE (version 2.1.2) using the GTR+F+I+G4 model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and it was rooted using the O’nyong-nyong virus as outgroup. Scale bar represents the average number of nucleotide substitutions per site. This analysis involved 57 nucleotide sequences. Red triangles denote the viral strains characterized in this study, whereas black circles represent the predominant circulating strains identified in La Réunion during 2024–2025.

Abbreviation: ECSA=East/Central/South Africa genotype; IOL=Indian Ocean Lineage; MAL=Middle African Lineage; SAL=South American Lineage; AAL=African/Asian Lineages.

The CHIKV genome encodes four nonstructural and five structural proteins. While nonstructural proteins are not incorporated into mature virions, structural proteins serve as critical targets for host humoral immune responses and represent the primary antigenic components in most vaccine formulations (4). Consequently, this study focused specifically on analyzing amino acid variation sites within these structural proteins. Genomic analysis revealed that both the GM01_ycj0728 and GM02_yzc0728 strains harbored several critical mutations, including E1-A226V, as well as the E2-L210Q and E2-I211T substitutions (Table 1).

Protein Protein position Viruses NC_004162 PV593524 GM01_ycj0728 GM02_yzc0728 C 23 P P P P C 27 V V V V C 63 K R R R C 73 K K K K E3 23 A T T T E2 57 G K K K E2 60 D D D D E2 74 I T T T E2 79 G E E E E2 160 N T T T E2 164 A T T T E2 181 L M M M E2 194 S G G G E2 198 R R R R E2 205 G G G G E2 210 L Q Q Q E2 211 I T T T E2 233 K K K K E2 252 K K K K E2 264 V V V V E2 267 M R R R E2 299 S N N N E2 312 T T T T E2 344 A T T T E2 375 S S S S E2 386 V V V V 6K 8 V V V V 6K 54 I V V V E1 98 A A A A E1 211 K K K K E1 226 A V V V E1 269 M V V V E1 284 D D D D E1 317 I V V V E1 322 V A A A Note: Bold text in the chart indicates amino acid positions where mutations were detected. Table 1. Non-synonymous mutations in the structural polyprotein of Chikungunya virus.

The E1-A226V mutation was first identified in 2005 and has been demonstrated to significantly increase CHIKV adaptation and replication competence in Ae. albopictus mosquitoes, although it is not considered the sole determinant of the virus’s high transmission efficiency (7,11). Notably, the additional acquisition of E1-K211E and E2-V264A mutations synergistically amplified CHIKV replication efficiency in Ae. aegypti, yielding exponential increases in viral load compared with the single E1-A226V variant (9). The sequences revealed only the E1-A226V mutation in both isolates, lacking the E1-K211E/E2-V264A combination. While E2-L210Q/I211T mutations synergize with E1-A226V to enhance Ae. albopictus-specific adaptation, this epistatic interaction has no significant effect on CHIKV performance in Ae. aegypti or standard vertebrate cell cultures (9). In Guangdong Province, Ae. albopictus serves as the predominant mosquito species, while the distribution of Ae. aegypti remains relatively limited. This ecological predominance of Ae. albopictus may represent a key contributing factor in the rapid import and subsequent widespread dissemination of the current epidemic.

-

CHIKV is a significant mosquito-borne pathogen that has undergone sustained transmission in all global regions inhabited by Aedes mosquitoes since 2005. Notably, the acquisition of adaptive mutations has increased the epidemic potential through increased transmissibility (12). In this study, it was confirmed that the circulating virus carries adaptive mutation sites such as E1-A226V, E2-L210Q, and E2-I211T, which have been demonstrated to significantly enhance viral replication efficiency in Ae. albopictus.

This study performed whole-genome sequencing of viral sequences from clinical samples, establishing a robust framework for CHIKV genomic surveillance and single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Specifically, meta-transcriptomic sequencing is recommended for emerging epidemic strains, as this method overcomes 3’ UTR amplification failures associated with primer-based whole-genome amplification approaches, thereby significantly increasing the likelihood of obtaining complete genomes. Second, during genome assembly, the selection of reference sequences should be guided by average nucleotide identity analysis — a strategy critical for ensuring the accuracy of CHIKV genome reconstruction. This approach addresses technical challenges such as the 3’ UTR gaps observed in consensus sequences when suboptimal references are used (e.g., the S27 genomic sequence in this study). Third, based on prior epidemiological and virological experimental data, this study identified 35 amino acid sites within structural proteins as high-priority surveillance targets, enabling efficient large-scale identification of critical mutations in genomic datasets.

The findings of this study are subject to at least two limitations. First, although genomic evolution was analyzed through average nucleotide identity and phylogenetic reconstruction, further investigations into 3’ UTR polymorphisms and short repetitive sequence elements would provide deeper insights into CHIKV adaptive evolution. Second, while high-frequency mutation sites in structural proteins are prioritized for surveillance, the biological significance of low-frequency mutations in nonstructural proteins remains to be elucidated.

-

Approved by The Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China (approval number: SZCDC-IRB2024033).

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: