-

Malaria remains a major global public health challenge and one of the most significant infectious diseases worldwide. According to the latest data released by the World Health Organization (WHO), there were approximately 263 million malaria cases and 597,000 deaths caused by malaria globally in 2023. Notably, the majority of these cases were attributed to Plasmodium falciparum infections in Africa (1). Malaria has been endemic in China for over 3,000 years. Through generations of effort, both the number of malaria cases and the extent of malaria-endemic areas have significantly decreased (2). In response to the global malaria elimination initiative outlined in the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, the Chinese government launched a nationwide campaign in 2010. This initiative set ambitious targets: to eliminate malaria in most regions in China by 2015 and to achieve nationwide malaria elimination by 2020. No local cases have been reported since 2017. On June 30, 2021, China was officially certified as a “malaria-free country” by the World Health Organization after successfully achieving the goals of its malaria elimination program.

However, in recent years, with the continuous advancement of economic globalization and the “Belt and Road” infrastructure initiative, China’s exchanges with countries around the world have become increasingly frequent. In particular, the number of workers traveling to malaria-endemic regions, such as Africa and Southeast Asia, has risen. As a result, imported malaria cases are now the primary source of malaria cases in China, presenting new challenges for malaria prevention and control in the country (3). Since 2017, China has reported zero indigenous mosquito-borne malaria cases. However, the risk of imported cases and their potential for secondary transmission persists. Therefore, malaria prevention and case management remain critical in China, with the goals of reducing severe malaria cases and deaths, and of preventing local secondary transmission (4).

Severe malaria is a potentially life-threatening complication of malaria infection. The pathophysiological progression from non-severe malaria to severe malaria involves complex host–parasite interactions that are influenced by both intrinsic factors, such as age and genetic susceptibility, and extrinsic factors, such as delayed diagnosis and chemoprophylaxis compliance (5).

Large-scale epidemiological assessments to describe trends and identify risk factors for severe malaria may improve imported malaria case management and prevent severe cases. To better understand and address this challenge, we retrospectively collected data on malaria case information nationwide from 2019 to 2023, using the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention Parasitic Disease Prevention and Control Information System (NIPD-PCIS). We conducted case-based epidemiological investigations on each imported malaria case and described its epidemiological characteristics, identified risk factors associated with severe malaria, and provided information for early detection and clinical management of severe malaria and to inform malaria treatment strategies early in the disease.

-

Malaria is an infectious parasitic disease caused by Plasmodium parasites. Diagnosis of malaria cases in this study was based on a comprehensive assessment of epidemiological history, clinical manifestations, and laboratory examinations, in accordance with the Health Industry Standards of the People’s Republic of China.

-

In confirmed malaria cases, the presence of one or more of the following clinical manifestations indicates severe malaria: coma, severe anemia (hemoglobin <5 g/dL or hematocrit <15%), acute renal failure (serum creatinine >265 μmol/L), pulmonary edema or acute respiratory distress syndrome, hypoglycemia (blood glucose <2.2 mmol/L or <40 mg/dL), circulatory collapse or shock (systolic blood pressure <70 mmHg in adults or <50 mmHg in children), and metabolic acidosis (plasma bicarbonate <15 mmol/L) (6). In clinical practice, physicians comprehensively evaluate patients’ symptoms, physical signs, laboratory findings, and disease progression to determine the presence of severe malaria. Patients infected with malaria parasites who present with mild symptoms, absence of high parasitemia, and no vital organ dysfunction or additional concerning laboratory indicators are classified as non-severe malaria cases.

-

China has established a comprehensive nationwide malaria reporting system that requires healthcare institutions at all levels, including hospitals and public health departments, to immediately report any diagnosed malaria case through the Disease Surveillance Information Reporting and Management System. Mandatory reporting fields include: 1) demographic data (name, age, sex, occupation, and current residence); 2) disease-related information (date of symptom onset, date of medical consultation, and history of prior malaria infections); 3) clinical manifestations (fever, chills, headache, and generalized myalgia); and 4) diagnostic results (parasitological test outcomes and Plasmodium species identification). For this study, epidemiological data of malaria cases from 2019 to 2023, including both clinical and parasitological information, were extracted from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention Parasitic Disease Prevention and Control Information System (NIPD-PCIS).

-

Summary statistics of normally distributed quantitative variables were expressed as means and standard deviations. For non-normally distributed variables, we used medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), and categorical data were summarized by ratios and percentages. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare median differences in continuous variables between groups, while the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to examine proportional differences. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with severe malaria, and the association between exposure variables and severe cases was estimated by odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

-

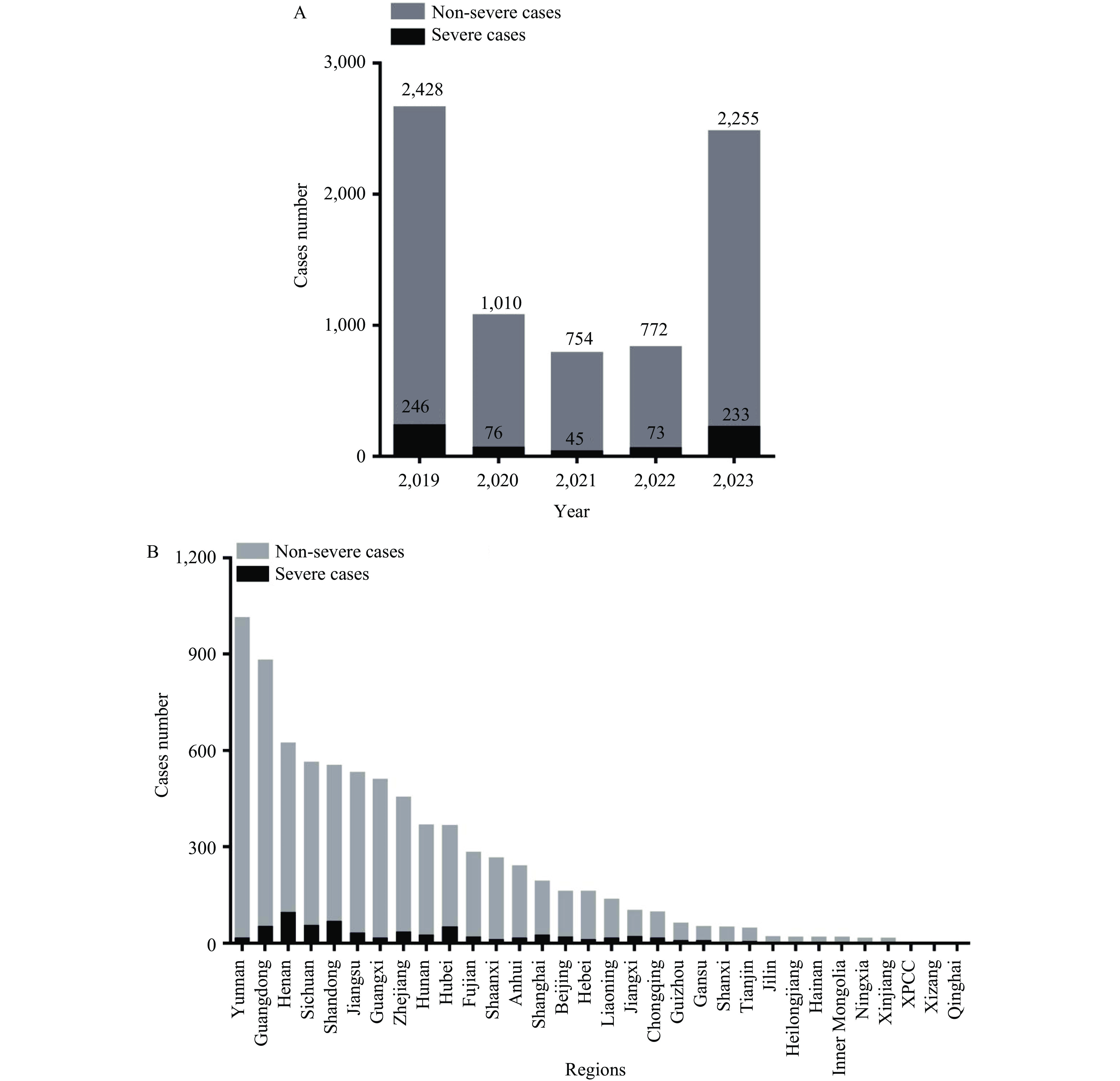

From 2019 to 2023, a total of 7,892 imported malaria cases were reported. All cases were divided into two groups according to the inclusion criteria mentioned in the methodology: severe malaria (673 cases) and non-severe malaria (7,219 cases), with a significant surge in severe cases in 2023 (Figure 1A). National distribution of imported malaria from 2019 to 2023 shows that the top five regions with the highest number of malaria cases are Yunnan, Guangdong, Henan, Sichuan, and Shandong provinces, while the top five provinces with severe malaria cases are Henan, Shandong, Sichuan, Guangdong, and Hubei (Figure 1B). Case characteristics are presented in Table 1, which showed that 7,352 (93.2%) patients were male and 539 (6.8%) patients were female, with a mean age of 41.0±11.3 years. The severe malaria group had an older mean age (43.9±10.4 years) compared to the non-severe malaria group (40.7±11.4 years). The majority of patients were overseas workers (79.8%). Among all the cases, 84.8% of the patients originated from Africa, 14.4% from Asia, 0.6% from Oceania, and 0.2% from South America. Notably, 95.5% of the severe malaria cases were from Africa. A total of 6,227 (78.9%) patients had a history of overseas residence within the past month and 4,898 (62.1%) within the past year, including 609 (90.5%) in the severe malaria group. Among the 7,892 patients, 76.9% were initially diagnosed with malaria. The malaria species were identified as 5,005 cases of P. falciparum, 1,524 cases of P. vivax, 1,031 cases of P. ovale, 248 cases of P. malariae, and 79 cases of mixed infection. Of the severe cases, 527 (78.3%) were caused by P. falciparum. Among all of the patients, 6,461 (81.9%) had a history of malaria infection. A total of 47 deaths occurred, all in the severe malaria group (7.0% of severe cases). Statistical analysis showed significant differences between the severe and non-severe malaria groups in terms of age, infection source, history of overseas residence within the past month, malaria species, and patient outcomes (P<0.05).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Distribution of severe and non-severe imported malaria in China. (A) Distribution of severe and non-severe imported malaria in China from 2019 to 2023; (B) National distribution of severe and non-severe malaria from 2019 to 2023.

Abbreviation: XPCC=Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.Factors Total

(N=7,892)Non-severe patient

(N=7,219)Severe patient

(N=673)Statistical

valueP Gender, N (%) 0.403 0.294 Male 7,353 (93.2) 6,721 (93.1) 631 (93.8) Female 539 (6.8) 497 (6.9) 42 (6.2) Age 41.0±11.3 40.7±11.4 43.9±10.4 −6.97 0.005 Purpose of travel, N (%) Labor 6,300 (79.8) 5,788 (80.2) 512 (76.1) 8.03 0.18 Tourism 92 (1.2) 86 (1.2) 6 (0.9) Others 1,500 (19.0) 1,345 (18.6) 155 (23.0) Source, N (%) Africa 6,690 (84.8) 6,047 (83.8) 643 (95.5) 93.92 0 Asia 1,137 (14.4) 1,113 (15.4) 24 (3.6) Oceania 49 (0.6) 45 (0.6) 4 (0.6) South America 16 (0.2) 14 (0.2) 2 (0.3) History of living abroad within one month, N (%) No 1,665 (21.1) 1,601 (22.2) 64 (9.5) 59.369 0 Yes 6,227 (78.9) 5,618 (77.8) 609 (90.5) History of living abroad in the past year, N (%) No 2,994 (37.9) 2,734 (37.9) 260 (38.6) 0.149 0.364 Yes 4,898 (62.1) 4,485 (62.1) 413 (61.4) Initial diagnosis, N (%) Malaria 6,071 (76.9) 5,555 (76.9) 516 (76.7) 0.026 0.871 Other diseases 1,821 (23.1) 1,664 (23.1) 157 (23.3) Species, N (%) Plasmodium falciparum 5,005 (63.4) 4,478 (62.0) 527 (78.3) 72.33 0 Plasmodium vivax 1,524 (19.3) 1,445 (20.0) 79 (11.7) Plasmodium ovale 1,031 (13.1) 984 (13.6) 47 (7.0) Plasmodium malariae 248 (3.1) 235 (3.3) 13 (1.9) Mixed 79 (1.0) 72 (1.0) 7 (1.0) others 5 (0) 5 (0) 0 (0) Previous malaria, N (%) No 1,431 (18.1) 1,325 (18.3) 106 (15.8) 2.789 0.51 Yes 6,461 (81.9) 5,894 (81.7) 567 (84.2) Outcome, N (%) Death 47 (0.6) 0 (0) 47 (7.0) 461.017 0 Survival 7,845 (99.4) 7,219 (100) 626 (93.0) Table 1. Epidemiological characteristics of malaria in China from 2019 to 2023.

-

The median time was 2 days (IQR: 1–4 days) from symptom onset to medical visit, 1 day (IQR: 0–2 days) from visit to diagnosis, and 1 day (IQR: 0–2 days) from diagnosis to treatment. In the severe malaria group, the median time was 4 days (IQR: 2–6 days) from symptom onset to medical visit, 2 days (IQR: 1–4 days) from visit to diagnosis, and 2 days (IQR: 0–3 days) from diagnosis to treatment. The corresponding times of the non-severe malaria group were 2 days (IQR: 1–4 days), 1 day (IQR: 0–2 days), and 1 day (IQR: 0–2 days), respectively. The median duration of medication was 7 days (IQR: 3–8 days) overall, 7 days (IQR: 5–9 days) in the severe malaria group, and 7 days (IQR: 3–8 days) in the non-severe malaria group. The median length of hospital stay was 5 days (IQR: 0–7 days) overall, 7 days (IQR: 5–10 days) in the severe malaria group, and 5 days (IQR: 0–7 days) in the non-severe malaria group. Mosquito nets for malaria prevention were used when traveling abroad by 5,634 patients (71.4%) overall, 498 patients (74%) in the severe malaria group, and 5,136 patients (71.1%) in the non-severe malaria group (Table 2). Statistical analyses showed significant differences between severe and non-severe malaria groups in the time from symptom onset to medical visit, time from visit to diagnosis, and time from diagnosis to treatment, and in the duration of medication and length of hospital stay (P<0.05).

Factors Total

(N=7,892)Non-severe patient

(N=7,219)Severe patient

(N=673)Statistical

valueP From onset to visit/d, median (IQR) 2 (1–4) 2 (1–4) 4 (2–6) −14.153 0 From visit to diagnosis/d, median (IQR) 1 (0–2) 1 (0–2) 2 (1–4) −15.39 0 From diagnosis to treatment/d, median (IQR) 1 (0–2) 1 (0–2) 2 (0–3) −3.48 0.003 Medication time/d (IQR) 7 (3–8) 7 (3–8) 7 (5–9) −9.298 0 Use bed nets during stay abroad, N (%) No 2,258 (28.6) 2,083 (28.9) 175 (26.0) 2.457 0.063 Yes 5,634 (71.4) 5,136 (71.1) 498 (74.0) Table 2. Diagnosis and treatment characteristics of malaria in China from 2019 to 2023.

-

In a univariate analysis, factors were associated with an increased risk of severe malaria, including age, source of infection, malaria type, history of living abroad within the past month, time from onset to visit, time from visit to diagnosis, and time from diagnosis to treatment. A multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that age (OR: 1.022, 95% CI: 1.014, 1.031), Africa as the infection source (OR: 2.902, 95% CI: 1.958, 4.299), Plasmodium falciparum as the causal pathogen (OR: 1.442, 95% CI: 1.159, 1.793), time from onset to visit (OR: 1.035, 95% CI: 1.021, 1.05), and a history of living abroad within the past month (OR: 2.207, 95% CI: 1.649, 2.955) were independent risk factors for developing severe malaria (Table 3).

Factors β SE Wald P OR (95% CI) Age 0.022 0.004 29.531 0 1.022 (1.014, 1.031) Source Others Africa 1.033 0.201 26.509 0 2.902 (1.958, 4.299) Species Others Plasmodium falciparum 0.37 0.111 11.042 0.001 1.442 (1.159, 1.793) From onset to visit 0.05 0.008 43.024 0 1.035 (1.021, 1.05) From visit to diagnosis 0 0 0.001 0.971 1 (1, 1) From diagnosis to treatment −0.026 0.015 3.125 0.077 0.974 (0.946, 1, 003) History of living abroad within the past month No Yes 0.792 0.149 28.298 0 2.207 (1.649, 2.955) Constant −7.381 0.310 567.888 0 0.001 Abbreviation: SE=standard error; OR=odd ratio; CI=confidence interval. Table 3. Multivariate logistic analysis of factors associated with the risk of severe malaria.

-

In 2017, China achieved zero reporting of indigenous malaria cases, marking a significant milestone in the country’s journey toward malaria elimination (7). However, with increasing international exchanges, the number of imported malaria cases has been rising in recent years, and the severe malaria rate among imported P. falciparum cases has reached 8.5% (673/7,892). Severe malaria is characterized by an acute onset, multiple severe complications, and high mortality (6). Therefore, rapid and effective diagnosis and treatment of imported malaria to prevent progression to severe malaria is critically important.

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed risk factors associated with severe imported malaria cases in China from 2019 to 2023. The results showed that increased age was associated with a higher risk of severe malaria. This finding aligns with WHO surveillance data showing that patients over 45 years had a 1.5 times higher mortality than younger adults (1). This may be attributed to weakened cellular immune functions and reduced splenic filtration capacity in elderly patients, thus reducing parasite clearance (8). Additionally, older patients often have comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases with associated endothelial dysfunction, which may exacerbate malaria-related complications (9).

Since the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000, China’s labor exports to Africa have continuously increased. Africa has the highest malaria burden globally, and infection in Africa is predominantly caused by P. falciparum (1). Previous studies and our data indicate that P. falciparum infection is a risk factor for severe malaria (10). These factors contribute to a significantly higher risk of severe malaria in patients from Africa compared to other regions, consistent with previous reports (11). Therefore, malaria education for travelers to Africa is particularly important.

Our study found that the time from symptom onset to medical visit was positively associated with the risk of severe malaria, consistent with many other studies (12). These findings emphasize the need for implementing standardized “test and treat” protocols within 24 hours of symptom onset, as recommended in the latest guidelines (6). The high risk associated with recent overseas residence within 1 month suggested that strengthened malaria diagnosis and treatment measures are needed for recent returnees, and that education and adoption of malaria knowledge among inbound and outbound travelers needs to be improved.

This study has several limitations: 1) The data were retrospectively analyzed. 2) Potential inconsistencies in adherence to malaria control measures among healthcare facilities in different regions may have introduced confounding variables. 3) The inclusion criteria were limited; clinical characteristics, such as comorbidities and genetic factors, and laboratory indicators, such as complete blood count and blood biochemistry, were not collected.

-

In summary, from 2019 to 2023, severe cases accounted for 8.5% of all malaria cases in China. Independent risk factors for severe malaria included advanced age, African infection source, P. falciparum infection, prolonged time from symptom onset to seeking medical attention, and history of residing abroad within the past month. Therefore, identifying these epidemiological characteristics and implementing prompt interventions are crucial for reducing the incidence and preventing re-transmission of severe malaria, thereby alleviating socioeconomic burdens and strengthening malaria eradication efforts. This study enriches the knowledge base regarding severe malaria risk factors and provides a valuable reference for effective case management strategies in the future.

-

Routine data were used from the NIPD-PCIS. All data were anonymized during the analysis.

HTML

Inclusion Criteria of Malaria Cases

Criteria for Classification as Severe and Non-Severe Malaria

Data Collection

Data Analysis

Epidemiological Profile

Diagnosis and Treatment Information

Abbreviation: Risk Factors for Severe Malaria

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: