HTML

-

Intestinal infections affect approximately 450 million people globally, predominantly children and immunocompromised individuals in low- and middle-income countries (1). These regions are particularly vulnerable due to poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions, coupled with poverty, malnutrition, and low literacy levels (2). It is estimated that over 3.5 billion people worldwide host at least one species of intestinal pathogen during their lifetime, contributing to extended hospital stays, increased healthcare costs, and higher disability-adjusted life years (DALY) (3–6).

In Kenya, the prevalence of intestinal infections is high due to the warm tropical climate and socioeconomic conditions (6–7). These infections, caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites such as protozoa and helminths, include common protozoa like Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Blastocystis spp., Entamoeba, and Cyclospora (8–10). Protozoa, transmitted primarily through the fecal-oral route, is spread by asymptomatic carriers and causes symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain (11–12). Despite the increasing impact of these infections, data on morbidity and mortality in Kenya are limited (13). With 80% of the country classified as arid or semi-arid and many relying on surface water, urgent interventions are needed (14–15).

To address the rising burden of intestinal protozoan infections in Kenya, large-scale surveillance and comprehensive One Health studies are needed to evaluate the prevalence, synthesize data, and identify risk factors for targeted interventions and informed policymaking.

-

The scoping review protocol was adapted from established methodologies (Figure 1). Scoping reviews are systematic reviews that map the breadth and scope of literature on a specific topic, in this case, protozoan pathogens in Kenya’s source water. The primary research questions were: What is the national prevalence of protozoan pathogens in Kenya’s source water intended for domestic consumption? What are the common genes/genotypes, contamination pathways, and available detection methods?

Literature searches were conducted between May 1 and May 21, 2024, using academic databases, including Science Direct, Google Scholar, African Journals Online (AJOL), and Springer Link. The search strategy focused on keywords related to enteric protozoa, including Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Kenya, urban centers, informal settlements, population groups (including children and adults), food handlers, and vulnerable groups such as immunocompromised individuals. Specific search term combinations included: “Protozoa and Kenya”, “Cryptosporidium and Kenya”, “Giardia and Kenya”, “Protozoa in informal settlements in Kenya”, “Protozoan infections of children in Kenya”, and “Protozoa in source water in Kenya”.

The search, unrestricted by year but limited to English-language articles, excluded review articles. Boolean operators were used to refine the search. Titles and abstracts were screened, and full texts were evaluated according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Papers meeting both the inclusion and exclusion criteria were retained for the final analysis.

The inclusion criteria were: 1) articles written in English; 2) original, full-text research articles; 3) studies based on One Health sample sources (human, animal, and environmental); and 4) analysis of enteric protozoa (Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Entamoeba, Cyclospora, Isospora, Blastocystis, and/or their oocysts or genetic markers) in One Health samples. Exclusion criteria were: 1) review papers that synthesized previously published data; 2) studies involving countries other than Kenya; 3) experimental studies focusing on protozoa detection efficiency using various methods; and 4) articles without extractable data.

-

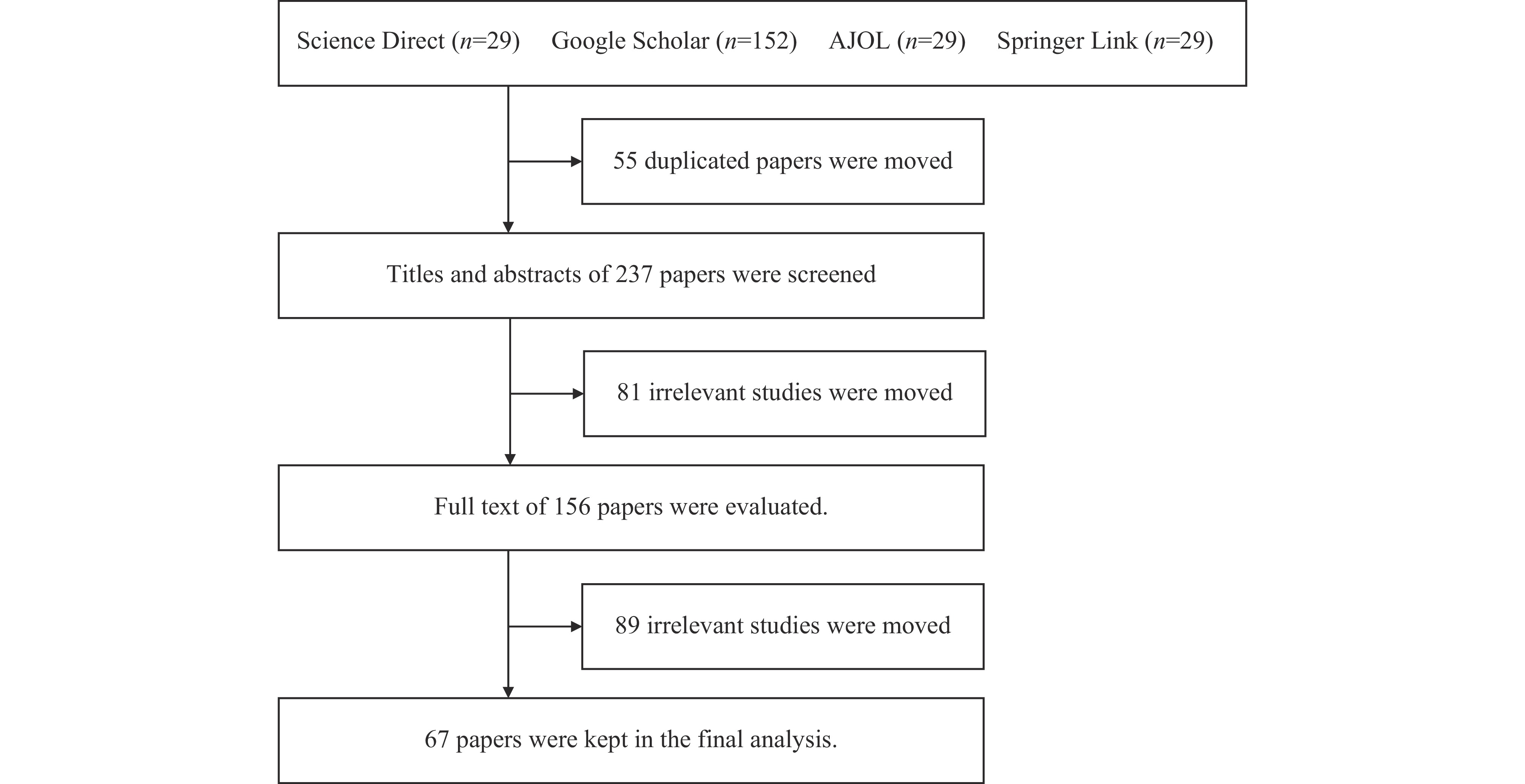

A total of 292 studies were initially retrieved from 4 databases. After removing 55 duplicates, 237 studies were screened by title and abstract, excluding 81 irrelevant studies. The remaining 156 articles underwent full-text evaluation, resulting in the exclusion of 89 papers that did not meet the inclusion or exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 67 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis.

-

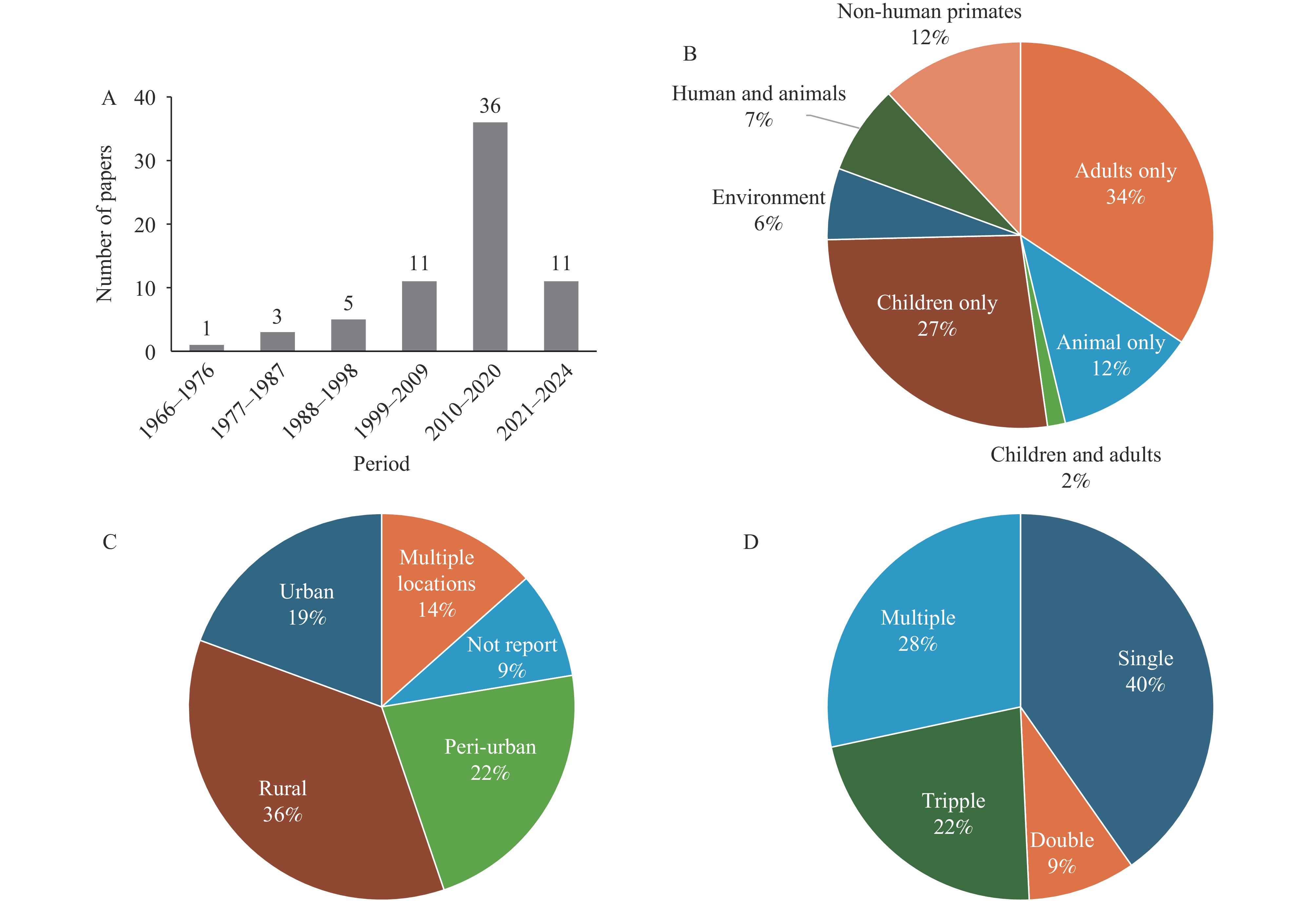

The studies included in this review were conducted between 1966 and 2024, with 54% (36 studies) published between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 2A). These studies predominantly focused on adults and children, with only 6% (4 studies) utilizing an “environmental surveillance” approach, sampling water and plants (16) (Figure 2B). Most were conducted in rural areas, followed by peri-urban and urban settings (Figure 2C). While 40% of the studies examined a single protozoan species, some investigated multiple species (Figure 2D).

-

Of the 67 studies, 37% used a cross-sectional design. Two used a retrospective design, and 2 used a prospective design.

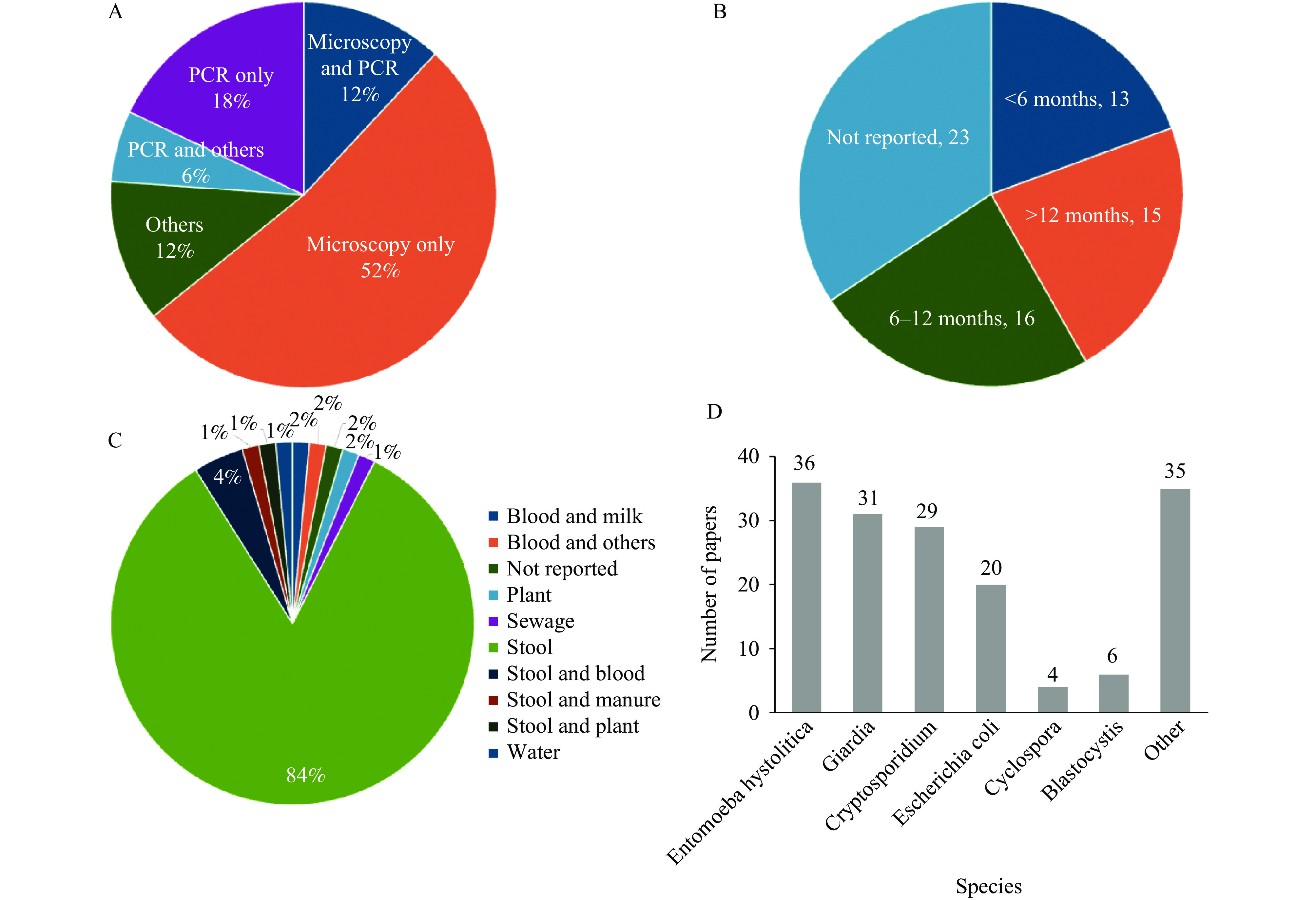

Microscopy was the most commonly used detection method (64%), primarily focusing on stool samples (Figure 3A and Figure 3C). Molecular studies, mainly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (36%), were mostly conducted in the last decade. The sampling duration was frequently unspecified. However, 20% of the studies were conducted for less than 6 months, while 24% were completed within 6 to 12 months (Figure 3B). Over 80% of the studies collected stool samples, with a few collecting environmental samples, such as water or sewage (Figure 3C).

-

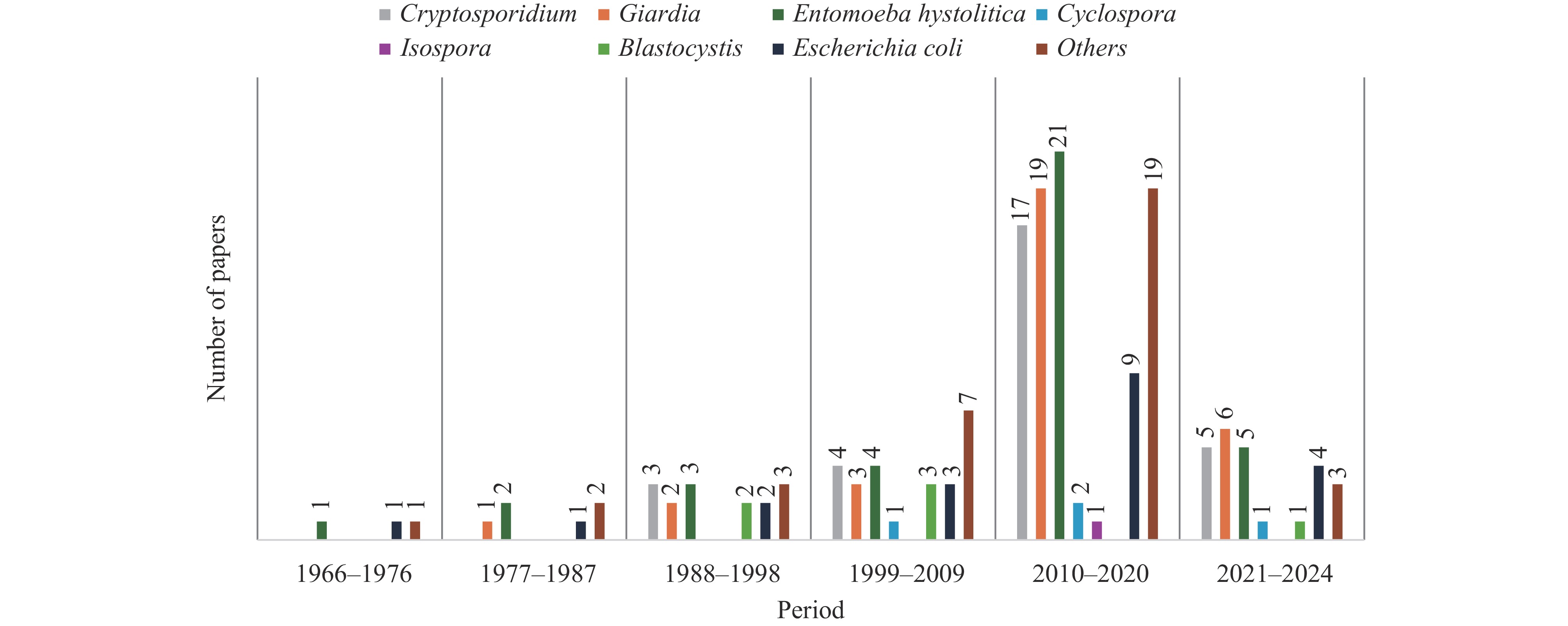

The top three prevalent protozoa in Kenya were Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium (Figure 3D). Detection numbers for most protozoa, including these three, exhibited an increasing trend over time, peaking between 2010 and 2020 (Figure 4). This trend aligns with the temporal distribution of research activities (Figure 2A).

Entamoeba histolytica remains a significant public health concern, having been previously isolated from various sources, including food handlers with valid health certificates, schoolchildren, inpatients and outpatients, De Brazza monkeys, and pigs (17–24). However, many studies used microscopy, which does not differentiate between E. histolytica and E. dispar.

Cryptosporidium is the second most prevalent protozoan, identified through microscopy and PCR in children (25–26), baboons (27), rivers (16,28–29), as well as during outbreaks of new genotypes in a military camp (30). Human studies frequently involved routine hospital samples from individuals with watery stools (31–33). The presence of livestock and untreated/contaminated water sources was identified as risk factors, but some studies suggested anthroponotic transmission due to overcrowding and poor WASH conditions (28,34–35). C. hominis was the most prevalent species in human infections, whereas C. parvum was more common in environmental and animal samples (36). Other Cryptosporidium species detected in Kenya include C. canis, C. felis, C. muris C. ryanae, and C. andersoni (35,37).

Giardia lamblia is recognized as one of the most prevalent intestinal protozoan infections both in Kenya and globally (38). It has been detected in children (22,39) and food handlers (18,40). Studies have identified unhygienic conditions, improper sewage disposal, and low socioeconomic status as significant risk factors for Giardia infections, while factors such as sex, constipation, and loss of appetite were not associated with its prevalence (41–42). Notably, there is limited information on the prevalence of Giardia in domesticated animals and its national distribution in Kenya (43). To date, only one study has investigated the prevalence and risk factors of Giardia infections in dogs, the most commonly kept pets in Kenya (44).

Entamoeba coli (E. coli) has been found in food handlers (17), preschool and school-aged children (6,39,45), households in low-altitude rural areas (41), pregnant women (46), pigs (47), and non-human primates (48–49). However, no studies specifically address its environmental prevalence despite its impact on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected patients (1,22,50) .

-

Current research on intestinal protozoa in Kenya relies primarily on patient-based data, often collected through questionnaires. However, studies investigating environmental sources, such as watersheds, to identify infection pathways are lacking. This limitation may be due to resource constraints, resulting in the use of stool microscopy and flow cytometry for diagnostics. While conventional, these methods lack the sensitivity and specificity of molecular diagnostic tests, leading to inaccurate estimations of the true prevalence of intestinal protozoa in the environment.

Socioeconomic status remains a critical factor influencing the prevalence of intestinal protozoan infections in Kenya (17). Environmental conditions such as rainfall, temperature, and humidity further impact parasite prevalence, highlighting the role of socio-demographic and geographic factors (51). In peri-urban areas, poor WASH conditions and overcrowding contribute to anthroponotic transmission (37). In rural settings, the common presence of domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, and dogs in close proximity to human dwellings is associated with higher infection rates (52). Rapid rural-to-urban migration has led to the growth of informal settlements, characterized by overcrowding, poor services, and high poverty levels (6,18,53). Despite these factors, no studies have quantified environmental contamination, particularly during rainy seasons when transmission may increase.

This scoping review provides a comprehensive analysis of the national prevalence of protozoan infections in Kenya, highlighting that current research primarily targets vulnerable groups, such as children and patients with diarrhea. However, significant gaps remain in the surveillance of environmental reservoirs, including watersheds, drinking water sources, irrigation water, and soil. Water treatment in Kenya predominantly relies on chlorination, which is ineffective against many protozoa. Consequently, there is limited data on the prevalence of intestinal protozoa in environmental and animal reservoirs, including domesticated animals, pets, and wildlife. Enhanced surveillance of these reservoirs, aligned with the One Health approach, is crucial for identifying infection sources and improving public health interventions.

-

A key limitation of this review is the insufficient epidemiological data on the transmission dynamics of protozoan infections in Kenya, highlighting the need for further studies to elucidate transmission risks and inform targeted public health interventions. Additionally, many existing studies focus on specific areas, often neglecting comprehensive environmental sampling and diverse animal reservoirs. The One Health approach, integrating human, animal, and environmental health, is essential for addressing zoonotic diseases. Although Kenya’s Zoonotic Disease Unit (ZDU) has made progress, its capacity for overseeing zoonotic parasite surveillance remains limited and requires enhancement. Increasing human encroachment into wildlife habitats, tourism, the exotic pet trade, and bushmeat demand, create new infection pathways. There is an urgent need for research on zoonotic parasites in wildlife, particularly primates, as no studies in Kenya have concurrently collected specimens from human, animal, and environmental sources for comparative analysis.

To improve future surveillance of intestinal infections within the One Health framework, developing integrated health monitoring systems that incorporate data from humans, animals, and the environment is crucial. Collaborative research initiatives among public health agencies, veterinary services, and environmental organizations should be promoted to facilitate data sharing and resource optimization. Engaging local communities, especially vulnerable populations, will significantly enhance data collection and awareness. A strategic focus on these areas is essential for mitigating the impact of intestinal infections and promoting overall health.

-

This review identifies significant gaps in the surveillance of intestinal protozoa, particularly within the environmental and animal health sectors. Socioeconomic and environmental factors, such as inadequate WASH conditions and human-animal interactions, influence intestinal protozoan infections in Kenya. The predominant protozoa — Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium, and Giardia — are often detected using less accurate stool microscopy. Persistent gaps in environmental and animal reservoir surveillance underscore the need for a comprehensive One Health strategy that includes broader sampling. Developing integrated health monitoring systems, fostering collaboration among relevant sectors, and engaging local communities, are crucial steps to strengthen surveillance efforts and mitigate the public health impact of intestinal infections.

General Characteristics of Protozoan-Related Studies in Kenya

Study Design and Detection Methods

Prevalence of Protozoa and Associated Predisposing Factors in Kenya

Overview of Current Intestinal Protozoa Studies in Kenya

Limitations and Recommendations

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: