-

Migration, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the movement of people from one area to another for varying periods, has significant public health implications (1). Men who have sex with men (MSM) in China are particularly vulnerable to HIV infection and are more likely to migrate due to widespread stigma and discrimination (2). Post-diagnosis migration of human immunodeficiency virus -positive (HIV-positive) MSM presents unique challenges for maintaining consistent care, tracking epidemic patterns, and ensuring equitable healthcare access — making it more consequential than other forms of migration within the HIV care continuum. Currently, the interprovincial movement patterns of HIV-positive MSM after diagnosis in China remain poorly understood. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of interprovincial migration was conducted to identify where HIV-infected or at-risk individuals require services and to strategically focus HIV management efforts. The findings reveal that approximately 10% of HIV-positive MSM migrated post-diagnosis, predominantly from affluent to less developed provincial-level administrative divisions (PLADs), highlighting the need for enhanced resources, improved case management, and tailored HIV services to support these migrants.

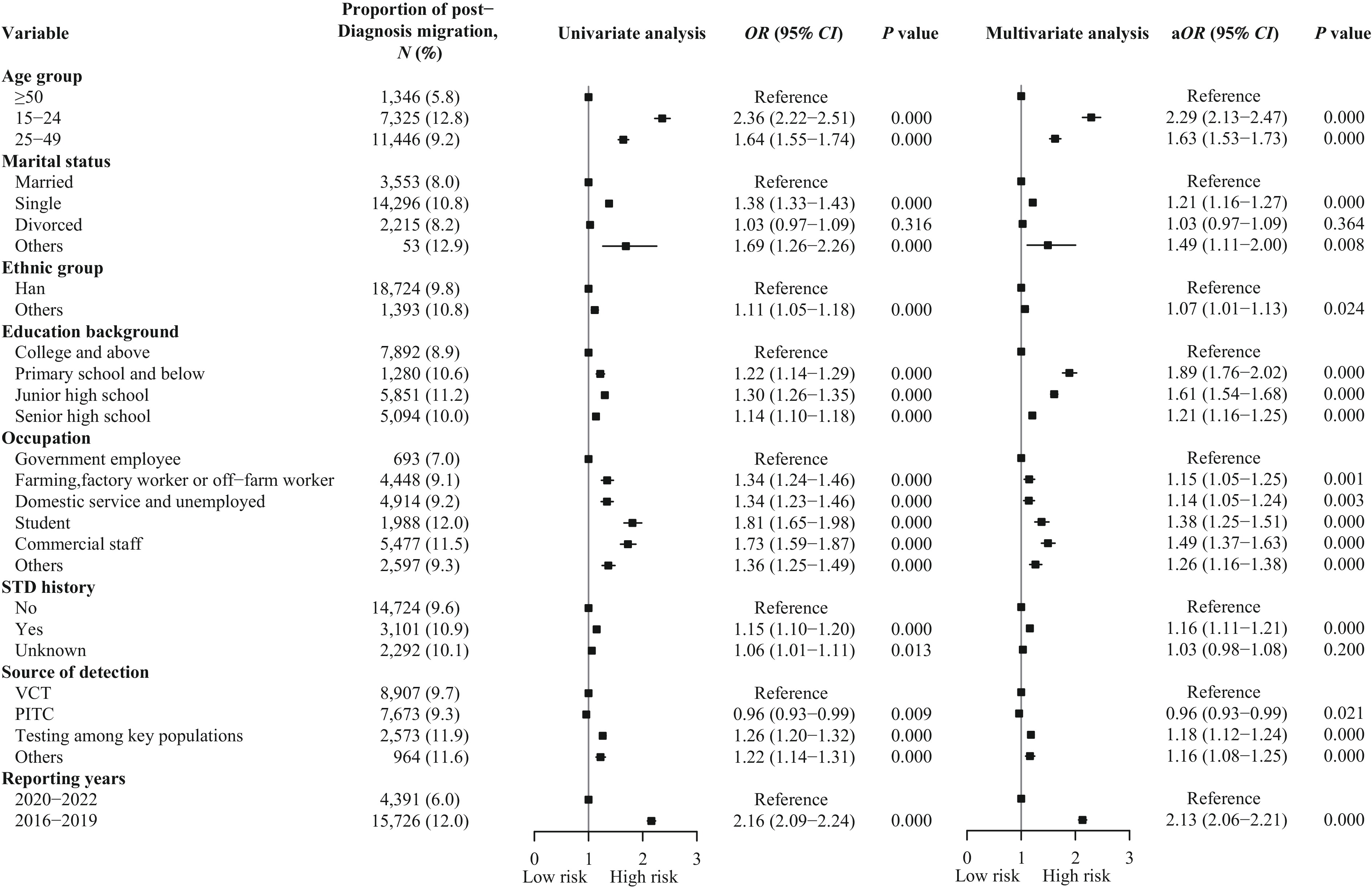

Data were extracted from the National Integrated HIV/AIDS Control and Prevention Data System. Study inclusion criteria were: 1) MSM; 2) age ≥15 years; 3) confirmed HIV-positive status through confirmatory testing; 4) experience of interprovincial migration. Participants were classified as MSM migrants if their follow-up addresses differed from their baseline addresses at diagnosis, while those with unchanged addresses were categorized as non-migrants (3). For cases with multiple address changes, the first change was considered as the inflow location. Data analysis was performed using R software (version 4.3.0; R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Univariable logistic regression was employed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for potential factors associated with migration among HIV-positive MSM. Subsequently, multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted through stepwise elimination to calculate adjusted ORs. The Ethics Review Board of the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention approved this study.

Among the 204,394 MSM diagnosed with HIV during the study period, 20,117 (9.8%) were identified as migrants based on post-diagnosis relocation. Significant demographic differences emerged between migrant and non-migrant MSM. Migrants were predominantly younger (36.4% vs. 27.2% aged 15–24), more likely to be unmarried (71.1% vs. 64.4%), and had lower educational attainment (60.8% vs. 56.0% with senior high school education or below). Occupationally, migrants showed higher proportions of commercial staff (27.2% vs. 22.9%) and students (9.9% vs. 7.9%). Migration rates decreased substantially during 2020–2022 (21.8%) compared to 2016–2019 (37.6%) (Table 1). Furthermore, migrant MSM demonstrated lower treatment initiation rates compared to non-migrants [91.3% (18,360/20,117) vs. 95.0% (174,998/184,277)] (χ2=485.7, P<0.001). Among migrants, 57.0% (1,467/20,117) initiated treatment before relocation, 33.8% (6,801/20,117) began treatment after relocation, and 9.2% (1,849/20,117) remained untreated.

Characteristics Non-migrant MSM

N (%) (n=184,277)Migrant

N (%) (n=20,117)Chi-square P Age group (years) 1,029.04 <0.001 15–24 50,084 (27.2) 7,325 (36.4) 25–49 112,478 (61.0) 11,446 (56.9) 50–65 18,536 (10.1) 1,203 (6.0) ≥66 3,179 (1.7) 143 (0.7) Marital status 368.10 <0.001 Married 40,653 (22.1) 3,553 (17.7) Unmarried 118,629 (64.4) 14,296 (71.1) Divorced 24,636 (13.4) 2,215 (11.0) Unknown 359 (0.2) 53 (0.3) Ethnic group 13.63 <0.001 Han 172,746 (93.7) 18,724 (93.1) Others 11,531 (6.3) 1,393 (6.9) Education background 217.19 <0.001 Primary school and below 10,818 (5.9) 1,280 (6.4) Junior high school 46,254 (25.1) 5,851 (29.1) Senior high school 46,062 (25.0) 5,094 (25.3) College and above 81,143 (44.0) 7,892 (39.2) Occupation 383.77 <0.001 Farming, factory worker & off-farm worker 44,199 (24.0) 4,448 (22.1) Domestic service &unemployed* 48,676 (26.4) 4,914 (24.4) Commercial staff† 42,231 (22.9) 5,477 (27.2) Student 14,614 (7.9) 1,988 (9.9) Government employee 9,224 (5.0) 693 (3.4) Others 25,333 (13.7) 2,597 (12.9) STD history 46.88 <0.001 Yes 25,378 (13.8) 3,101 (15.4) No 138,559 (75.2) 14,724 (73.2) Unknown 20,340 (11.0) 2,292 (11.4) Source of detection 242.38 <0.001 PITC 74,741 (40.6) 7,673 (38.1) Testing among key populations§ 19,033 (10.3) 2,573(12.8) Others 7,366 (4.0) 964 (4.8) VCT 83,137 (45.1) 8,907 (44.3) Reporting years 1,961.53 <0.001 2016–2019 114,954 (62.4) 15,726 (78.2) 2020–2022 69,323 (37.6) 4,391 (21.8) Abbreviation: HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; PITC=provider-initiated testing and counselling; VCT=voluntary counseling and testing; STD=sexually transmitted disease; MSM=men who have sex with men.

* Domestic service included housekeepers and caregivers, etc., and “Unemployed” contained job seekers, temporarily unemployed, stay-at-home parents and laid-off workers, etc.

† Commercial staff included individuals employed in various commercial sectors such as retail, sales, marketing, business services, and other non-sex work related commercial activities.

§ Testing among key populations included premarital examination, screening of spouses or sexual partners of individuals living with HIV, testing of children born to HIV-positive women, screening of blood donors, and health examinations for individuals in entertainment venues, those entering or leaving the country, and new recruits, etc.Table 1. Demographic characteristics of HIV-positive MSM categorized by provincial-level migration status in China, 2016–2022.

The migration patterns of HIV-positive MSM predominantly involved key out-migrating and in-migrating PLADs. Among the 20,117 HIV-positive MSM who migrated, 10,244 (50.9%) were initially diagnosed in economically developed PLADs. The PLADs with the highest numbers of out-migrating cases were Guangdong, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Beijing, and Jiangsu (Figure 1A). Analysis of migration destinations revealed that 86.4% (8,854/10,244) of these individuals relocated to PLADs corresponding to their household registration place for follow-up. Specifically, of 21,974 MSM diagnosed in Guangdong, 2,376 (10.8%) migrated to other PLADs, with 2,063 (86.8%) returning to their household registration place. Among 6,907 MSM diagnosed in Shanghai, 2,208 (32.0%) relocated, with 2,028 (91.8%) returning to their household registration place. Of 11,790 MSM diagnosed in Zhejiang, 2,085 (17.7%) migrated, with 1,808 (86.7%) returning to their household registration place. For 11,521 MSM diagnosed in Beijing, 1,956 (17.0%) migrated, with 1,604 (82.0%) returning to their household registration place. Among 14,823 MSM diagnosed in Jiangsu, 1,619 (10.9%) migrated, with 1,351 (83.4%) returning to their household registration place. The PLADs with the highest proportion of out-migrating cases were Shanghai (2,208/6,907, 32.0%), Zhejiang (2,085/11,790, 17.7%), Beijing (1,956/11,521, 17.0%), Tianjin (530/3,483, 15.2%), and Fujian (632/4,645, 13.6%) (Figure 1B). The top five PLADs receiving in-migrating cases were Sichuan (1,532 cases), Anhui (1,497 cases), Henan (1,486 cases), Guangdong (1,268 cases), and Hunan (1,116 cases), collectively accounting for 34.3% of all migrant MSM (Figure 1C). The PLADs with the highest proportion of in-migrating cases were Jiangxi (888/3,372, 26.3%), Anhui (1,497/7,803, 19.2%), Guangxi (704/4,688, 15.0%), Hunan (1,116/7,888, 14.2%), and Henan (1,486/11,527, 12.9%) (Figure 1D). Notable migration corridors with over 300 cases included Beijing-Hebei (474 cases), Shanghai-Anhui (434 cases), Jiangsu-Anhui (410 cases), Guangdong-Hunan (409 cases), Guangdong-Guangxi (397 cases), and Zhejiang-Anhui (300 cases).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.The out-migration and in-migration of HIV+ MSM among key PLADs regarding numbers and proportion, 2016–2022. (A) Top five PLADs with highest out-migrant numbers; (B) Top five PLADs with the highest proportion of out-migrants; (C) Top five PLADs with highest in-migrant numbers; (D) Top five PLADs with the highest proportion of in-migrants.

Note: This figure showed the top five PLADs in terms of out-migrant and in-migrant numbers/proportions in PLADs. Abbreviation: HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; MSM=men who have sex with men; PLAD=provincial-level administrative division.Analysis of migration-related factors revealed several significant associations. Compared to those aged ≥50 years, individuals aged 15–24 years had a higher likelihood of migration [adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=2.29, 95% CI: 2.13, 2.47], as did those aged 25–49 years (aOR=1.63, 95% CI: 1.53, 1.73). Being unmarried was associated with increased migration (compared to married individuals, aOR=1.21, 95% CI: 1.16, 1.27). Lower education levels showed a clear gradient effect, with primary school and below (aOR=1.89, 95% CI: 1.76, 2.02), junior high school (aOR=1.61, 95% CI: 1.54, 1.68), and senior high school (aOR=1.21, 95% CI: 1.16, 1.25) all showing higher migration rates compared to college education and above. Occupation also influenced migration patterns, with commercial staff (aOR=1.49, 95% CI: 1.37, 1.63) and students (aOR=1.38, 95% CI: 1.25, 1.51) more likely to migrate than government employees. Additional risk factors included having STD history (aOR=1.16, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.21), being identified through testing among key populations (aOR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.12, 1.24), and being diagnosed between 2016–2019 (aOR=2.13, 95% CI: 2.06, 2.21) (Figure 2).

-

This study reveals significant patterns of post-HIV diagnosis migration among MSM in China, characterized by initial diagnosis in economically developed regions followed by return migration to household registration locations in central and western PLADs for follow-up care. Key factors associated with post-diagnosis migration include age under 50, unmarried status, lower educational attainment, employment as commercial staff or student status, STD history, and diagnosis before 2020.

The findings indicate that approximately 10% of HIV-positive MSM relocated between diagnosis and follow-up, exceeding the migration rate of the general HIV-positive population (7.8%). This elevated mobility among MSM reflects complex intersections of cultural, economic, and health-related factors. Young, single individuals with lower educational attainment and STD history demonstrated higher mobility patterns. These younger, single individuals typically exhibit greater sexual activity, and their engagement in high-risk behaviors during migration may facilitate HIV transmission to the general population, making them crucial targets for intervention strategies. Limited educational attainment often restricts employment opportunities, necessitating increased geographical mobility in search of better prospects. This mobility, combined with potentially limited HIV awareness, increases vulnerability to high-risk sexual behaviors during migration, contributing to HIV transmission patterns (4). Commercial staff, characterized by complex social networks, present particular challenges for AIDS response due to their inherent mobility. Additionally, the marked decrease in migration during 2020–2022 likely reflects the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic restrictions, including travel limitations, lockdowns, and economic uncertainty.

Economically developed regions, particularly Guangdong, Beijing, and the Yangtze River Delta (Shanghai-Zhejiang-Jiangsu), attract MSM due to their superior employment opportunities, enhanced anonymity, and greater social acceptance. However, the findings reveal that many MSM subsequently return to their home PLADs, including Anhui, Henan, Sichuan, Hunan, and Hebei, for follow-up care. This pattern aligns with the “coming home” phenomenon described in previous research, which identified proximity to family as the primary motivator for relocation among HIV-infected individuals (5). HIV-positive MSM may face heightened privacy concerns and social stigma in metropolitan areas, making smaller cities or their places of household registration more appealing (6). These familiar environments often provide greater acceptance and understanding (7). This contrasts with findings from the United States, where HIV-positive individuals typically migrate to larger urban centers post-diagnosis, attracted by more favorable healthcare policies, particularly liberal Medicaid coverage (8).

Local insurance policies emerge as crucial determinants of migration patterns. Despite China’s provision of free HIV treatment, non-local MSM encounters significant barriers, including variable testing fees and reduced reimbursement rates, which often compel them to return to their home PLADs. This migration can delay treatment initiation, potentially increasing the risk of drug resistance. Pre-treatment testing fees in major cities vary considerably, ranging from full reimbursement to complete self-payment, imposing substantial economic burdens on migrant patients (9). Furthermore, out-of-province treatment restrictions, including lower reimbursement rates, complex administrative procedures, and extended reimbursement cycles, contribute to patient outflow. It is recommended establishing a streamlined, cross-provincial reimbursement system with a centralized digital platform for efficient claim processing and tracking is recommended. Notably, the findings indicate that a significant proportion of patients-initiated treatment post-migration, increasing their risk of drug resistance. This observation parallels U.S. research showing that 11.3% of HIV-positive individuals discontinued treatment during travel periods (10).

These findings underscore the necessity for targeted services to promote timely treatment among the nearly one-third of migrant MSM who delay treatment initiation. It is recommended that economically developed PLADs consider relaxing household registration requirements, streamlining administrative processes, and reducing policy barriers for non-local residents. Additionally, major cities should enhance transparency in medical insurance policies and ensure timely communication of policy changes to maximize accessibility for non-local patients.

Beyond the major economic centers, PLADs such as Tianjin and Fujian demonstrate notable post-diagnosis out-migration patterns, highlighting the need for comprehensive management protocols for non-local patients. These protocols should encompass strengthened treatment referral mechanisms and enhanced HIV prevention and control measures. The significant inflow to PLADs like Anhui, Henan, and Hunan necessitates effective case management strategies in both origin and destination regions to prevent HIV transmission. To facilitate this, it is recommended that incentive structures be implemented for local governments, such as the allocation of additional funding and resources based on migrant case management metrics. Furthermore, establishing robust partnerships between local health departments, NGOs, and community-based organizations would enable comprehensive care delivery for this mobile population. It is suggested that proactive information-sharing systems and coordinated healthcare provider networks among affected PLADs be implemented to ensure continuity of care and follow-up services. This integrated approach represents an effective long-term strategy for HIV/AIDS management from both public health and individual care perspectives.

This study has several limitations. First, this study only analyzed migration patterns between initial diagnosis and follow-up visits, leaving the precise timing and location of HIV acquisition unknown. Second, detailed data on the time interval between diagnosis and initial follow-up were lacking, highlighting the need for more comprehensive temporal data collection in future research. Despite these limitations, the large sample size and broad geographic coverage of the study provide valuable insights into post-diagnosis migration patterns and significant implications for HIV prevention among mobile HIV-positive MSM populations. Additionally, information on economic status and behavioral characteristics were not examined. Future studies should address these factors to better understand how mobility influences and enhances AIDS response strategies.

The evidence of substantial post-diagnosis migration among HIV-positive MSM in China underscores the critical need for policymakers to address the unique HIV prevention and care requirements of this mobile population. Specifically, tailored behavioral interventions and continuous treatment support must be readily accessible at both origin and destination locations to effectively control HIV transmission and ensure treatment adherence. Implementing comprehensive care strategies throughout the migration process can better protect the health of HIV-positive MSM, reduce transmission rates, and improve treatment outcomes in China.

-

We would like to express our gratitude to The Public Health Advanced Training Program (PHATP) supported by the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: