-

Pneumoconiosis frequently leads to pulmonary fibrosis and compromised lung immunity in affected individuals. Given the irreversible nature of pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis remains a preventable but currently incurable occupational disease (1). The reduced lung immunity in these patients often precipitates multiple complications, including emphysema, tuberculosis, and lung cancer (2). These comorbidities significantly complicate both the prevention and treatment of pneumoconiosis, with existing research demonstrating elevated mortality rates among pneumoconiosis patients with concurrent health conditions (3).

This study presents a comprehensive medical analysis of 5,791 deceased pneumoconiosis patients. Through detailed examination of the fundamental causes of death, This study aims to elucidate the primary mortality factors among these patients, evaluate the impact of various causes of death on their life expectancy, and provide evidence-based insights to inform future prevention and treatment strategies for pneumoconiosis.

-

This study analyzed data from the Jiangsu Province pneumoconiosis follow-up online reporting system. The study cohort comprised 5,791 deceased patients with complete follow-up information recorded between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2023. The cohort included 5,387 male and 404 female patients, with ages at death ranging from 32 to 101 years (mean: 76.63±8.98 years). Two patients with silicosis and other types of pneumoconiosis, respectively, died at ages exceeding 100 years. Data from 15,838 surviving patients were used to construct a simplified life table for pneumoconiosis patients in Jiangsu Province.

-

Data collection encompassed patients’ occupational industry, pneumoconiosis type, disease stage at diagnosis, primary cause of death, age at diagnosis, and post-diagnosis survival time. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0, IBM, Chicago, USA) and R software (version 4.4.1, Ross Ihaka, Auckland, New Zealand). One-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) was employed to compare intergroup means, while the Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for multivariate survival analysis. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

The primary cause of death was classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death (ICD) (4). This was defined as the initial disease or injury that initiated the sequence of pathological events leading directly to death, or the accident or violent event causing fatal injury. Causes of death were categorized as: lung infection, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, gastrointestinal tumors, lung tumors, trauma and other accidents, other tumors, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and other diseases (including sudden death, massive hemorrhage from gastrointestinal ulcer, and acute and chronic organ failure).

Occupational industries were classified according to the GB/T 4754-2017 Classification of National Economic Industries. Using follow-up data from 15,838 surviving patients in the online reporting system as of December 2023, we constructed both a simplified life table and a cause-specific life table. These analyses were conducted to evaluate the life expectancy of pneumoconiosis patients and quantify the impact of different causes of death on their life expectancy (5).

-

Among the 5,791 pneumoconiosis patients, males comprised 93.02% of the cohort, significantly outnumbering females (6.98%). The occupational distribution revealed that mining (58.47%), manufacturing (20.55%), and public management, social security, and social organizations (16.42%) were the predominant sectors, collectively accounting for 95.44% of cases. Silicosis (69.42%) and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis (20.57%) were the most prevalent types, representing 89.99% of all cases. The majority of patients (66.47%) were diagnosed with stage one pneumoconiosis (Table 1).

Factor Number Percentage (%) Gender Male 5,387 93.02 Female 404 6.98 Industry Industry 3,386 58.47 Manufacturing industry 1,190 20.55 Public administration, social security and social organizations 951 16.42 Electricity, heat, gas and water production and supply 106 1.83 Construction 79 1.36 Wholesale and retail 22 0.38 Residential services, repair and other services 17 0.29 Agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry and fishery 14 0.24 Water conservancy, environment and public facilities Management 10 0.17 Culture, sports and entertainment 5 0.09 Leasing and business services 4 0.07 Health and social work 3 0.05 Education 2 0.03 Real estate 1 0.02 Scientific research and technology services 1 0.02 Types of pneumoconiosis Silicosis 4,020 69.42 Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis 1,191 20.57 Founder pneumoconiosis 146 2.52 Asbestosis 121 2.09 Cement pneumoconiosis 110 1.90 Kaolin pneumoconiosis 76 1.31 Other pneumoconiosis diseases 56 0.97 Welder’s pneumoconiosis 47 0.81 Carbon black pneumoconiosis 7 0.12 Talcosis 7 0.12 Aluminosis 6 0.10 Graphite pneumoconiosis 2 0.03 Mica pneumoconiosis 2 0.03 Diagnosis period Phase I pneumoconiosis 3,849 66.47 Phase II pneumoconiosis 1,401 24.19 Phase III pneumoconiosis 541 9.34 Table 1. Patient characteristics of 5,791 deceased pneumoconiosis patients.

-

The average age at diagnosis for the 5,791 deceased patients with pneumoconiosis was 58.52±11.38 years, with an average post-diagnosis survival time of 18.12±11.21 years. Patients diagnosed with stage I pneumoconiosis exhibited a higher mean age at diagnosis compared to those with stages II and III. Conversely, stage II patients demonstrated longer post-diagnosis survival times than those with stages I and III. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences in both diagnostic age and post-diagnosis survival time across all pneumoconiosis stages (P<0.05) (Table 2).

Diagnosis period Average age at diagnosis (years) Average survival time after diagnosis (years) Phase I pneumoconiosis 58.88±11.21 F=6.847

P<0.0517.72±10.93 F=19.479

P<0.05Phase II pneumoconiosis 58.00±11.61 19.68±11.46 Phase III pneumoconiosis 57.24±11.87 16.86±12.45 Amount to 58.52±11.38 18.12±11.21 Table 2. Survival time of 5,791 deceased pneumoconiosis patients.

-

Analysis of the 5,791 deaths reveals four predominant causes of mortality: pulmonary infections (37.32%), cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (22.71%), gastrointestinal tumors (14.57%), and lung tumors (11.97%). For patients with stage I and II pneumoconiosis, the mortality pattern follows this same hierarchical order. However, in stage III pneumoconiosis patients, while pulmonary infections and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases remain the leading causes, lung tumors supersede gastrointestinal tumors as the third most common cause of death. These findings demonstrate that pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and lungs constitute the principal causes of mortality across all stages of pneumoconiosis (Table 3).

underlying cause of death Phase I pneumoconiosis Phase II pneumoconiosis Phase III pneumoconiosis Amount to Number Percentage (%) Rank order of causes of death Number Percentage (%) Rank order of causes of death Number Percentage (%) Rank order of causes of death Number Percentage (%) Rank order of causes of death Pulmonary infection 1,223 31.77 1 591 42.18 1 347 64.14 1 2,161 37.32 1 Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases 970 25.20 2 285 20.34 2 60 11.09 2 1,315 22.71 2 Gastrointestinal tumors 606 15.74 3 195 13.92 3 43 7.95 4 844 14.57 3 Lung tumors 496 12.89 4 146 10.42 4 51 9.43 3 693 11.97 4 Other diseases 181 4.70 5 56 4.00 5 14 2.59 6 251 4.33 5 Accidents such as trauma 148 3.85 6 52 3.71 6 15 2.77 5 215 3.71 6 Other tumors 121 3.14 7 44 3.14 7 8 1.48 7 173 2.99 7 Diabetes 75 1.95 8 27 1.93 8 2 0.37 8 104 1.80 8 Parkinson’s disease 29 0.75 9 5 0.36 9 1 0.18 9 35 0.60 9 Table 3. Cause of death of 5,791 deceased pneumoconiosis patients.

-

Using 2023 follow-up data from 15,838 surviving pneumoconiosis patients in Jiangsu Province, we constructed a simplified life table. Based on age-specific mortality probabilities and assuming a cohort of 10,000 pneumoconiosis patients aged 30 to <35 years, we calculated the number of surviving patients and expected life expectancy for each age group. The analysis projects an average life expectancy of 15.83 years for these pneumoconiosis patients (Table 4).

Age group (years) Number of observers Actual number of deaths Mortality Probability of death Number of survivors Death toll Survival years Total survival years Life expectancy 30–34 14 1 0.071,4 0.303,0 10,000 3,030 42,424 158,327 15.83 35–39 65 2 0.030,8 0.142,9 6,970 996 32,359 115,903 16.63 40–44 140 5 0.035,7 0.163,9 5,974 979 27,422 83,544 13.98 45–49 329 20 0.060,8 0.263,9 4,995 1,318 21,679 56,122 11.24 50–54 789 36 0.045,6 0.204,8 3,677 753 16,502 34,443 9.37 55–59 1,141 140 0.122,7 0.469,5 2,924 1,373 11,188 17,941 6.14 60–64 1,372 316 0.230,3 0.730,8 1,551 1,134 4,922 6,754 4.35 65–69 3,183 741 0.232,8 0.735,8 418 307 1,320 1,832 4.39 70–74 5,357 1,012 0.188,9 0.641,6 110 71 375 512 4.64 75–79 4,263 1,143 0.268,1 0.802,6 40 32 118 137 3.47 80–84 2,856 1,223 0.428,2 1.034,1 8 8 19 19 2.44 ≥85 2,120 1,152 0.543,4 1.000,0 0 0 0 0 0 Note: The probability of death in the age group ≥85 years old is 1. Table 4. Brief life table of follow-up patients with pneumoconiosis in Jiangsu Province in 2023.

-

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of life expectancy using multiple cause-specific life tables. The baseline life table for pneumoconiosis patients was compared with life tables excluding specific causes of death, including pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, gastrointestinal tumors, lung tumors, trauma and accidents, other tumors, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, and other conditions. The summarized findings are presented in Table 6. It was observed that the life expectancy of patients who succumbed to pulmonary infections was notably prolonged. Examination of Table 5 reveals extremely low or zero mortality rates were observed in the 35–45 year age group, which could introduce statistical bias, the analysis primarily focused on the 45–50 year age group. After excluding individual causes of death, the increases in life expectancy were: pulmonary infections (3.75 years), cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (1.11 years), gastrointestinal tumors (1.31 years), lung tumors (0.63 years), other diseases (0.31 years), trauma and accidents (0.23 years), other tumors (0.36 years), diabetes (0.07 years), and Parkinson’s disease (0.01 years). These findings demonstrate that pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, gastrointestinal tumors, and lung tumors have the most substantial impact on life expectancy in pneumoconiosis patients.

Age group (years) Number of observers Total number of deaths from all causes Deaths from pulmonary infections Death rate due to lung infection Probability of death Survival Probability Free from pulmonary infections Survival Probability Number of survivors Death toll Survival years Total survival years Life expectancy 30–34 14 1 0 1.000,0 0.303,0 0.697,0 0.697,0 10,000 3,030 42,424 216,620 21.66 35–39 65 2 2 0 0.142,9 0.857,1 1.000,0 6,970 0 34,848 174,196 24.99 40–44 140 5 5 0 0.163,9 0.836,1 1.000,0 6,970 0 34,848 139,347 19.99 45–49 329 20 10 0.500,0 0.263,9 0.736,1 0.858,0 6,970 990 32,374 104,499 14.99 50–54 789 36 17 0.527,8 0.204,8 0.795,2 0.886,1 5,980 681 28,197 72,125 12.06 55–59 1,141 140 60 0.571,4 0.469,5 0.530,5 0.696,1 5,299 1,610 22,468 43,928 8.29 60–64 1,372 316 100 0.683,5 0.730,8 0.269,2 0.407,8 3,689 2,184 12,982 21,460 5.82 65–69 3,183 741 206 0.722,0 0.735,8 0.264,2 0.382,5 1,504 929 5,199 8,478 5.64 70–74 5,357 1,012 272 0.731,2 0.641,6 0.358,4 0.472,3 575 304 2,118 3,279 5.70 75–79 4,263 1,143 413 0.638,7 0.802,6 0.197,4 0.354,8 272 175 920 1161 4.27 80–84 2,856 1,223 519 0.575,6 1.034,1 0 0 96 96 241 241 2.50 ≥85 2,120 1,152 557 0.516,5 1.000,0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Note: The probability of death in the age group ≥ 85 years old is 1. Table 5. Brief current life table of causes of lung infection in 2023 follow-up patients with pneumoconiosis in Jiangsu Province.

Age group (years) Life expectancy for all causes of death Life expectancy free from lung infections Life expectancy free from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases Life expectancy free from digestive tract tumors Life expectancy free from lung tumors Life expectancy free from other diseases Life expectancy free from trauma and accidents Life expectancy free from other tumor Life expectancy free from diabetes Life expectancy free from Parkinson’s disease 30–34 15.83 21.66 16.39 16.49 16.15 21.79 15.90 16.01 15.85 15.83 35–39 16.63 24.99 17.43 17.57 17.09 16.79 16.73 16.89 16.66 16.63 40–44 13.98 19.99 14.91 15.09 14.52 14.18 14.10 14.29 14.02 13.99 45–49 11.24 14.99 12.35 12.55 11.87 11.47 11.37 11.60 11.28 11.24 50–54 9.37 12.06 10.28 10.54 9.85 9.68 9.55 9.49 9.43 9.37 55–59 6.14 8.29 6.85 6.99 6.68 6.47 6.37 6.28 6.21 6.14 60–64 4.35 5.82 4.96 5.16 4.97 4.55 4.60 4.54 4.40 4.36 65–69 4.39 5.64 5.09 5.31 5.08 4.53 4.55 4.50 4.43 4.40 70–74 4.64 5.70 5.32 5.25 5.19 4.75 4.76 4.76 4.72 4.67 75–79 3.47 4.27 3.93 3.73 3.74 3.53 3.56 3.53 3.53 3.51 80–84 2.44 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.50 ≥85 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Table 6. The impact of different causes of death on life expectancy (years).

-

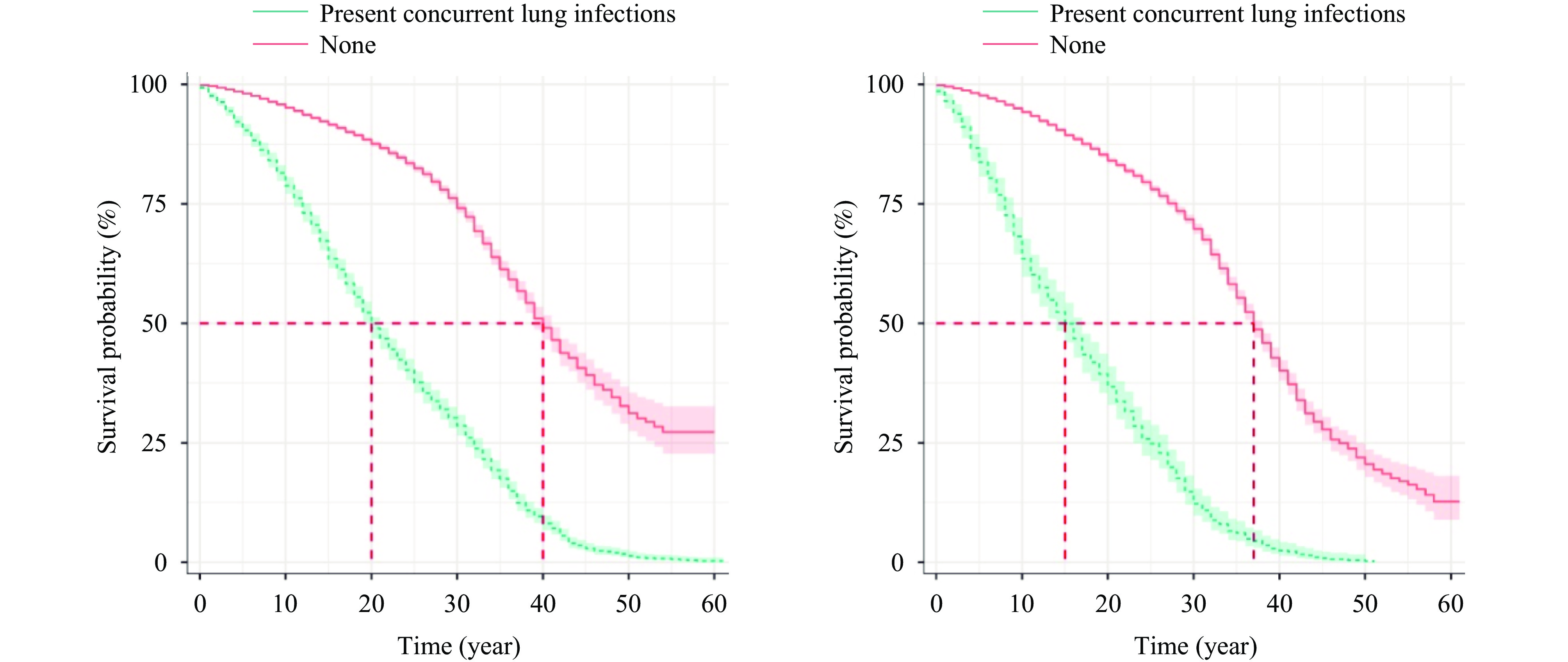

Using the Cox proportional hazards regression model to analyze factors affecting pneumoconiosis patient survival time, we identified several significant predictors of mortality (P<0.05): concurrent lung tumors, concurrent lung infections, age at diagnosis, gender, pneumoconiosis stage, and dust exposure duration (Table 7). The presence of lung tumors emerged as the strongest risk factor, increasing mortality risk by 7.797-fold. Pulmonary infections substantially elevated mortality risk (relative risk=3.030), as illustrated in Figure 1. Disease stage showed a progressive relationship with mortality risk (relative risk=1.110), while male patients demonstrated a 1.186-fold higher mortality risk compared to females. Advanced age at diagnosis was associated with increased mortality risk (relative risk=1.134). Dust exposure duration showed minimal impact on survival time, with a relative risk approaching unity (0.992).

Regression variables Regression coefficient Standard error Z P Hazard ratio RR 95% CI Upper limit Lower limit Diagnosed age 0.125 0.002 67.724 < 0.001 1.134 1.130 1.138 Gender 0.171 0.059 2.908 0.004 1.186 1.057 1.331 Diagnosis period 0.104 0.024 4.29 < 0.001 1.110 1.058 1.164 Dust exposure duration −0.008 0.002 −5.088 < 0.001 0.992 0.989 0.995 pulmonary infection 1.174 0.034 34.926 < 0.001 3.236 3.030 3.456 Lung tumors 2.054 0.048 42.736 < 0.001 7.797 7.096 8.567 Note: Categorical variable assignment, gender (female=0, male=1), pulmonary infection (none=0, present=1), pulmonary tumor (none=0, present=1).

Abbreviation: CI=confidence interval, RR=relative risk.Table 7. Coxmodel screening of risk factors and parameter estimation for pneumoconiosis death.

-

This study reveals a strong correlation between pneumoconiosis mortality and occupational distribution, with the mining sector accounting for 58.47% of cases and a predominant male patient population (93.02%). In Jiangsu Province, occupational exposure primarily involves silica and coal dust, which is reflected in the disease distribution: silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis collectively represent 89.99% of cases. These findings emphasize the critical need for enhanced occupational health measures within high-risk industries, particularly in mining. Implementation of comprehensive occupational health protection protocols and systematic health surveillance for workers in high-risk positions is essential, with emphasis on early monitoring, protection, diagnosis, and treatment from initial exposure (6).

Analysis of diagnostic timing, primary mortality causes, and cause-specific mortality rates demonstrates that pulmonary infections are the predominant direct cause of death, accounting for 37.32% of cases. This finding aligns with research by Reese et al. (7), which identified genetic variations in telomerase reverse transcriptase and telomerase RNA components among pneumoconiosis and asbestosis patients. These telomerase gene mutations accelerate telomere shortening, exacerbating progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease progression, altering lung architecture, and elevating infection susceptibility. The study identifies pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and gastrointestinal and lung tumors as the primary mortality causes in pneumoconiosis patients. Recent research highlights the increasing significance of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions, particularly hypertension and coronary heart disease, as major public health concerns (8). Stage III pneumoconiosis is notably associated with severe symptomatology and poor prognosis, primarily due to complications including immunocompromise and pulmonary infections (9-10).

These findings underscore the necessity for a comprehensive management approach to pneumoconiosis treatment, emphasizing both pulmonary fibrosis management and the treatment of associated complications and chronic conditions. The statistically significant differences in diagnosis age and post-diagnosis survival time across pneumoconiosis stages (P<0.05) highlight the importance of thorough and timely patient evaluation, particularly for stage III patients, to address complications and reduce mortality risk.

The study’s findings indicate that a substantial proportion of pneumoconiosis patients (66.03%) are diagnosed at stage I, suggesting significant potential for improving quality of life through appropriate therapeutic interventions (11–12). The identification of gastrointestinal and lung tumors as major mortality factors emphasizes the need for targeted research on improving outcomes for pneumoconiosis patients with concurrent malignancies. Life table analyses reveal that patients aged 30–34 years have an approximate life expectancy of 15.83 years. The primary factors affecting life expectancy include pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and digestive tract and lung tumors. Given that pneumoconiosis patients are typically older and often present with comorbidities such as malignancies and cardiovascular conditions, pulmonary infections represent a frequent and significant complication. These factors substantially influence both survival duration and quality of life, aligning with previous research findings (13-14). The positive nodules characteristic of pneumoconiosis not only represent typical pathological manifestations but also provide an optimal microenvironment for pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fungi. These nodules significantly increase infection susceptibility by compromising local immune responses. The impaired pulmonary function caused by nodules and fibrosis often leads to rapid clinical deterioration post-infection, resulting in poor therapeutic outcomes and shortened survival periods. Thus, the relationship between pulmonary infections and positive nodules may represent a primary mechanism underlying reduced life expectancy in pneumoconiosis patients. While cardiovascular and gastrointestinal diseases have less impact than pulmonary infections, they remain significant prognostic factors, possibly due to systemic effects of dust exposure, including chronic inflammatory responses. Future research exploring the relationship between positive nodules and systemic inflammatory responses may enhance our understanding of their impact on pneumoconiosis patients.

Future prevention and control strategies for pneumoconiosis should prioritize occupational health protection in high-risk industries through robust health surveillance and examination programs. While actively treating the primary condition, comprehensive management of complications and chronic comorbidities is essential. Particular attention should focus on stage III pneumoconiosis patients, ensuring thorough evaluation of all clinical parameters to facilitate early intervention for various complications. Scientific and meticulous treatment approaches, including aggressive management of pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and digestive tract and lung tumors, can potentially extend survival and enhance quality of life for the majority of pneumoconiosis patients.

There are some limitations in this study, such as the lack of data of patients who died directly from pneumoconiosis and the failure to collect clinical data such as smoking history of patients. Future studies will improve these shortcomings.

In addition to actively treating pneumoconiosis, clinicians must prioritize the management of complications and chronic conditions. Aggressive treatment of pulmonary infections, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and gastrointestinal and pulmonary tumors can significantly extend patient survival and enhance quality of life.

HTML

Study Population

Statistical Analysis

Patient Characteristics

Survival Time

Cause of Death

Life Expectancy of Pneumoconiosis Patients

The Impact of Different Causes of Death on Life Expectancy

Important Factors Influencing the Survival Time of Pneumoconiosis Patients

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: