-

The global challenge of population aging has become increasingly pressing, with the elderly population particularly vulnerable during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, facing an elevated risk of mortality. In China, the government has implemented a range of measures to reduce the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the elderly. However, despite these efforts, it is likely that some elderly individuals will still succumb to the virus, especially after policy relaxations. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the measures and strategies employed to address the challenges facing the elderly during the pandemic, while also proposing innovative approaches to reduce COVID-19 mortality in the context of an aging population.

-

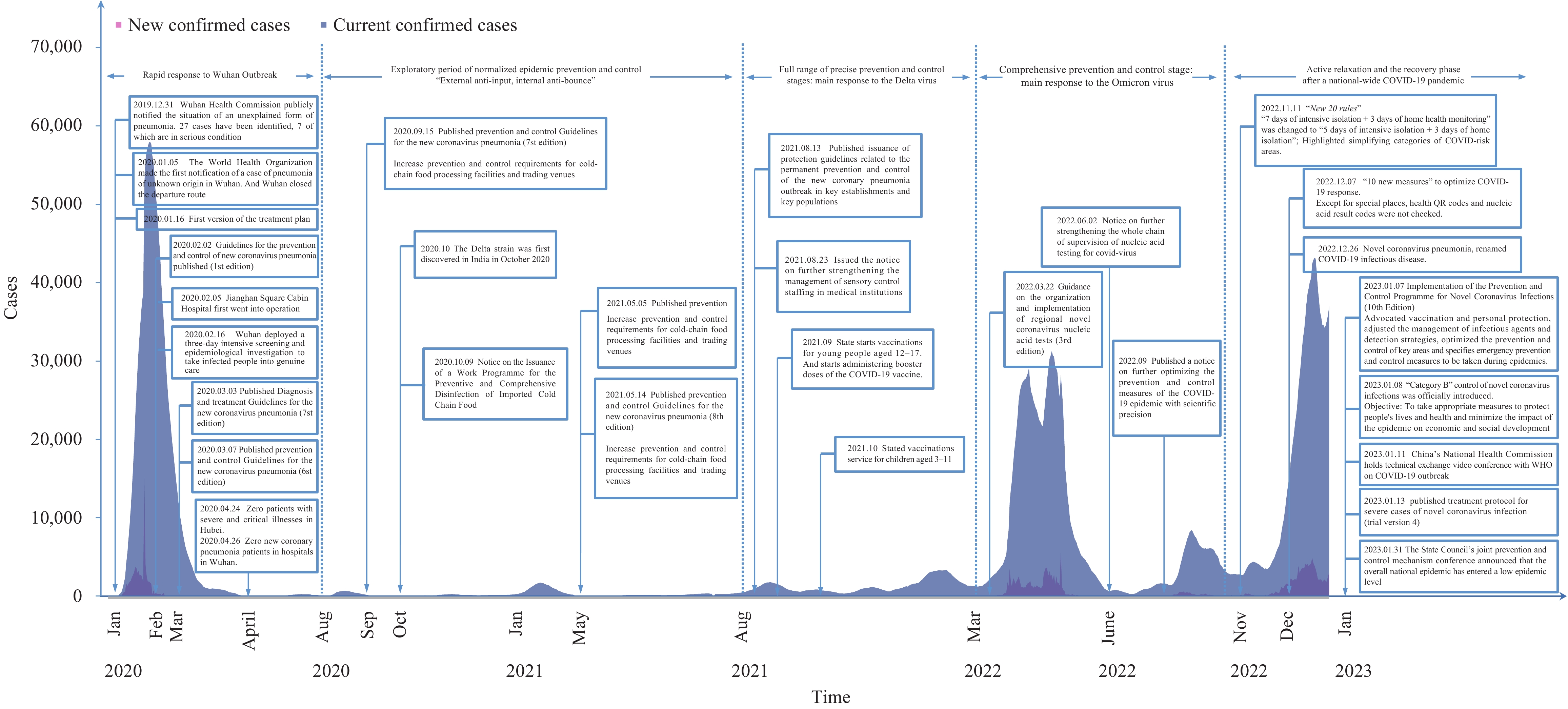

The COVID-19 epidemic in China can be divided into five phases based on the government’s response strategy and the epidemiological characteristics of the disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Policy measures and new & current confirmed cases by stages during the COVID-19 epidemic (January 2020 to January 2023).

Note: Data resources were up to 20 December 2022.

Abbreviation: COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019.

During Phase 1 of the outbreak period in December 2019, China quickly implemented non-pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) strategies and measures to identify the pathogen and control the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Wuhan. On January 20, person-to-person transmission was officially confirmed, and COVID-19 was added to the national Class B infectious disease list. Class A infectious disease prevention and control measures were adopted, and direct online reporting was mandated. As a result of the top-level emergency response being launched in time, the COVID-19 epidemic growth slowed down and the scale of the epidemic spread was limited. Research found that older people were the main susceptible group during this period, with 68% of the patients being over 50 years of age (1).

In Phase 2, the Chinese government adjusted its overall prevention and control strategy to prioritize the prevention of both external importation and internal rebound. To handle concentrated outbreaks, the government analyzed experiences from managing epidemics in different regions and provided guidance to local authorities to improve five measures: rapid response through the chain of command, nucleic acid screenings, extensive isolation of high-risk populations, centralized treatment for infected patients, and prompt release of information.

In Phase 3 of the precision prevention and control stage, the Chinese government revised its prevention and control strategy and implemented a “dynamic zero-COVID” approach in response to the transmission of the Delta variant. In August 2021, in response to the Delta variant outbreak at Nanjing Lukou International Airport, the government implemented several measures to enhance its epidemic control and mitigation strategies, including outpatient fever surveillance and mandated testing for key populations. These measures enabled the government to improve its disease surveillance capabilities and timely reporting of epidemiological data, and were effective in managing the risk of outbreak expansion. This successful implementation of these measures demonstrates China’s preparedness and agility in responding to emerging infectious disease threats.

In January 2022, the emergence of the highly transmissible and insidious Omicron variant in Tianjin and Henan posed a new challenge to epidemic prevention and control in China. In response, the Chinese government acted swiftly to promote the “antigen screening & nucleic acid diagnosis” surveillance model, enhance isolation and treatment capacity, improve nucleic acid testing, and ensure quality daily medical services for the public. As a result of these enhanced measures, China was able to achieve the ambitious goal of “dynamic zero” and maintain low case numbers during the first four waves of the COVID-19 epidemic (Figure 1). This comprehensive prevention and control phase was essential in containing the spread of the virus.

In Phase 5, active relaxation and post-pandemic recovery occurred across the region. As the epidemic situation changed, vaccination spread, and experience in prevention and control accumulated, China began to relax its strict epidemic control strategy. The “10 New Measures” and “20 New Rules” were launched to optimize COVID-19 response, and on December 26, 2022, the national implementation of COVID-19 downgraded from the current top-level Category A to the less stringent Category B. This marked a new stage in the prevention and control of the epidemic in China.

-

Overall, older individuals are at a higher risk of mortality due to COVID-19, particularly those aged 80 or older (2). A study published in February 2020 analyzed data from over 44,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China and found that the overall case fatality rate was 2.3%. However, the fatality rate was much higher for individuals aged 70–79 (8.0%) and those aged 80 or older (14.8%) (3). Additionally, comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes were also found to be significant risk factors for COVID-19 mortality (4).

Following the relaxation of epidemiological policies, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of elderly individuals in China has been substantial. Between December 2022 and January 2023, approximately 90% of the reported 59,938 COVID-19-related deaths occurred in individuals aged 65 years and older, with more than half of these deaths occurring in those aged 80 years and older (5).

-

Despite the reduced pathogenicity and virulence of the Omicron variant compared to the Delta or original strains, studies from both China and other countries indicate that older adults remain a high-risk group for COVID-19 infections. Given China’s large elderly population, safeguarding their health is of paramount importance during the peak of the epidemic.

China faces a shortage of medical resources, particularly critical care resources, which is exacerbated by an uneven distribution of resources in rural areas, disproportionately impacting elderly individuals. To address outbreaks in these areas, the government has placed a strong emphasis on epidemic prevention and control. To effectively mitigate the impact of limited medical resources in rural areas and improve health outcomes for vulnerable populations, it is essential to ensure timely access to medical supplies, including medications and vaccines, and to refer severe cases to higher-level hospitals and well-equipped medical facilities.

Early research has revealed that the sequelae of COVID-19 include prolonged immunosuppression, pulmonary, cardiac, and vascular fibrosis, pathological fibrosis of organs and arteries, increased mortality, and severe impairment in quality of life (6). However, further investigation is needed to understand the growth of COVID-19 after the acute period. According to research from King’s College London, Omicron is half as likely as Delta to cause a “long COVID” at 4.5%. As the number of people infected with Omicron increases, so will the absolute number of people with “long COVID”. Currently, 2 million people in the UK have Neonic pneumonia sequelae, 31% of whom were reported during the Omicron pandemic (7). Special attention should be given to the mental health of the elderly following infection (8).

The available vaccine against COVID-19 has had a profoundly positive impact during the epidemic, reducing the number of hospitalizations and deaths (9). However, those at risk of the serious consequences of COVID-19, particularly the elderly, require ongoing booster vaccination to maintain this level of protection. Additionally, the emergence of a new dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant approximately every 3 to 4 months presents a public health dilemma and uncertainty about the future (10). There is a risk that eventually, a variant will emerge and evade the protection against severe disease offered by the current generation of vaccines. Therefore, it is essential to consider the development of an improved SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that offers longer-lasting protection and broader coverage, given the need to maintain effective disease control measures.

-

Chronic health conditions, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes, as well as advanced age, have been identified as risk factors for severe COVID-19 and mortality. The management of chronic diseases has been greatly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, with many countries experiencing disruptions, particularly when in-person consultations with physicians are required (11). This has been exacerbated by the shift of medical resources from regular services to COVID-19-related care and treatment, leading to a substantial backlog of cases. As a result, the management of chronic diseases has become even more complex during the pandemic, and the issue of “long COVID” is a concern for patients even after the pandemic has subsided (12). It is essential to reinforce primary care capacity, policies, and environmental support to ensure the sustainable management of chronic diseases now and in the future, particularly considering the pandemic's long-term impact on population health services.

Real-world data demonstrate that vaccination is effective in reducing hospitalization and rates of severe illness in older people following infection. However, the elderly population, who are at risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19, require booster vaccinations to maintain this level of protection, as well as repeated vaccinations for those at risk. The emergence of a new dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant approximately every 3 to 4 months poses a public health dilemma (13). With the massive spread of COVID-19 in China, it is necessary to continue to monitor the outbreak closely for early detection of any new variants that may emerge. There is also a risk that a variant will eventually emerge that can evade protection against serious diseases from the current generation of vaccines (9). Therefore, it is essential to accelerate the development of a significantly improved SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that will provide longer and wider protection for the older population.

China’s successful implementation of the “dynamic zero policy” in combating COVID-19 is largely attributed to its robust capacity for social mobilization. To further improve the response to the pandemic, there is a need to reinforce social mobilization efforts and augment reserves of medical resources, such as drugs and vaccines. This can be achieved through measures like establishing specialized channels, setting up temporary vaccination sites, and deploying mobile vaccination vehicles to reach elderly individuals, as well as providing active door-to-door follow-up and vaccination services for elderly individuals who are disabled or semi-disabled. Additionally, it is crucial to prioritize the medical needs of non-COVID patients, particularly those requiring intensive care, while simultaneously maintaining ongoing medical treatment for elderly patients requiring procedures like dialysis and oncology chemotherapy. Many experiences in epidemic prevention abroad are also worth drawing upon. For instance, the UK government established an elderly assistance plan to provide emergency assistance and support (14), and the Japanese government implemented similar measures, such as providing home meal delivery service, increasing medical assistance resources, and offering up-to-date epidemic prevention information to the elderly through official websites (15). To establish a proactive, methodical, and aging-first strategy for resource deployment and social mobilization, it is necessary to overcome the "last mile" of vaccination and ensure maximum convenience for the elderly.

-

No conflicts of interest.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: