-

Belgian scholars in consumers of sausages first described botulism in 1896 (1). It was confirmed that the growth and germination of toxins occurred only under particular conditions in an anaerobic low salt, low-acid environment. People who ingest food contaminated with botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) produced by botulinum toxin can have a potentially fatal outcome (2). Outbreaks have been reported worldwide. In Canada, the first Clostridium botulinum type E outbreak in 1944 in Nanaimo, British Columbia was reported in 1947 (3); In China, Wu et al. first reported botulism in Xinjiang in 1958 due to edible semi-finished noodle sauce (4). A better understanding of the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks can help tailor local prevention and public health response strategies. Here, we reviewed surveillance data on outbreaks, illnesses, and deaths of botulism in China from 2004 to 2020.

-

Data were collected from 22 provincial-level administrative divisions (PLADs) in the mainland of China, and surveillance data of 50 outbreaks were abstracted from the database of the National Foodborne Disease Surveillance Network. Handsearching identified 30 publications from Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data, and Chinese Science and Technique Journals from January 2004 to December 2020 to identify indexed publications in the Chinese literature using the following search terms: “botulism,” “botulinum toxin,” or “Clostridium botulinum” combining “outbreaks.” Foodborne botulism outbreaks were performed by descriptive statistical analyses. We analyzed the number and proportion of outbreaks, illnesses, deaths and case-fatality rate, date of the outbreak, regional distribution, implicated food(s), contributing factors, locations of food preparation, serotype, and circumstances of occurrence. Statistical analysis of the data was done in SPSS (version 19, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and significance was defined as P<0.05.

-

From 2004 to 2020, a total of 80 foodborne botulism outbreaks occurred in China, involving 386 illnesses and 55 deaths; a 14.25% overall case-fatality rate of foodborne botulism outbreaks was reported in China (Table 1). Also, the case-fatality rate dramatically decreased from 57.69% (15/26) in 2004 to 38.46% (5/13) in 2020. Households had the largest proportion of outbreaks, accounting for 90.00% (72/80), and the most commonly implicated foods were home-prepared traditional processed stinky tofu in Xinjiang and dried beef in Qinghai households, accounting for 43.06% (31/72) of the total.

PLADs No. of outbreaks

(%)No. of illnesses

(%)No. of deaths

(%)Annual

averageNo. of

misdiagnoses*Case-fatality

rate† (%)Serotype§ Setting¶ Adjusted

χ2**p Type A Type B Household Xinjiang†† 20(25.00) 53(13.63) 4(7.27) 4 3 8.00 11 4 18 0.64 0.14 Qinghai 13(16.25) 101(26.17) 18(32.73) 13 4 17.82 0 0 13 Hebei 9(11.25) 23(5.96) 0(0.00) 8 2 0.00 1 3 9 Gansu 5(6.25) 17(4.40) 9(16.36) 3 2 52.94 0 0 4 Guizhou 4(5.00) 14(3.63) 4(7.27) 4 0 28.57 1 2 4 Henan 3(3.75) 15(3.89) 0(0.00) 5 1 0.00 1 2 3 Guangdong 3(3.75) 6(1.55) 0(0.00) 2 1 0.00 1 1 2 Shaanxi 3(3.75) 10(2.59) 1(1.82) 3 2 10.00 5 2 3 Tibet 2(2.50) 42(10.88) 3(5.45) 21 0 7.14 1 0 2 Jiangxi 2(2.50) 8(2.07) 0(0.00) 4 1 0.00 0 0 2 Shanxi 2(2.50) 5(1.30) 0(0.00) 3 0 0.00 0 0 2 Anhui 2(2.50) 17(4.40) 6(1.25) 9 0 35.29 1 0 2 Sichuan 2(2.50) 19(4.92) 9(16.36) 10 0 47.37 1 1 2 Yunnan 2(2.50) 27(6.99) 1(1.82) 14 1 3.70 0 0 1 Hunan 1(1.25) 2(0.52) 0(0.00) 2 1 0.00 1 1 0 Jiangsu 1(1.25) 1(0.26) 0(0.00) 1 1 0.00 1 0 1 Guangxi 1(1.25) 2(0.52) 0(0.00) 2 1 0.00 1 1 1 Shandong 1(1.25) 4(1.04) 0(0.00) 4 1 0.00 1 1 1 Ningxia 1(1.25) 11(2.85) 0(0.00) 11 1 0.00 0 0 1 Jilin 1(1.25) 3(0.78) 0(0.00) 3 0 0.00 0 0 1 Beijing 1(1.25) 2(0.52) 0(0.00) 2 0 0.00 1 0 0 Inner Mongolia 1(1.25) 4(1.04) 0(0.00) 4 0 0.00 0 1 0 Total 80(100.00) 386(100.00) 55(100.00) 5 22 14.25 28 18 72 Abbreviation: PLAD=provincial-level administrative division.

* Misdiagnosis: Patients with botulism can be misdiagnosed as having other illnesses such as Guillain-Barré Syndrome, common cold, malnutrition and myasthenia gravis.

† Case-fatality rate = number of deaths / number of illnesses.

§ Serotype: the remaining includes 26 serotypes not identified and 3 type E, 2 type AB, 2 types Mangan and 1F.

¶ Setting: the remaining 2 outbreaks occurred in unit canteens, 1 outbreak occurred in school canteens, supermarkets, stores and large restaurants respectively; 2 outbreaks not identified.

** The Adjusted chi-square test (χ2) of case-fatality rate between Xinjiang and Qinghai was performed and the result was: Adjusted χ2=2.22, P>0.05.

†† 20 cases of botulism in Xinjiang include 3 in Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps.Table 1. Number and proportion of foodborne botulism outbreaks, illnesses, deaths, serotype, and setting by PLAD, China, 2004–2020.

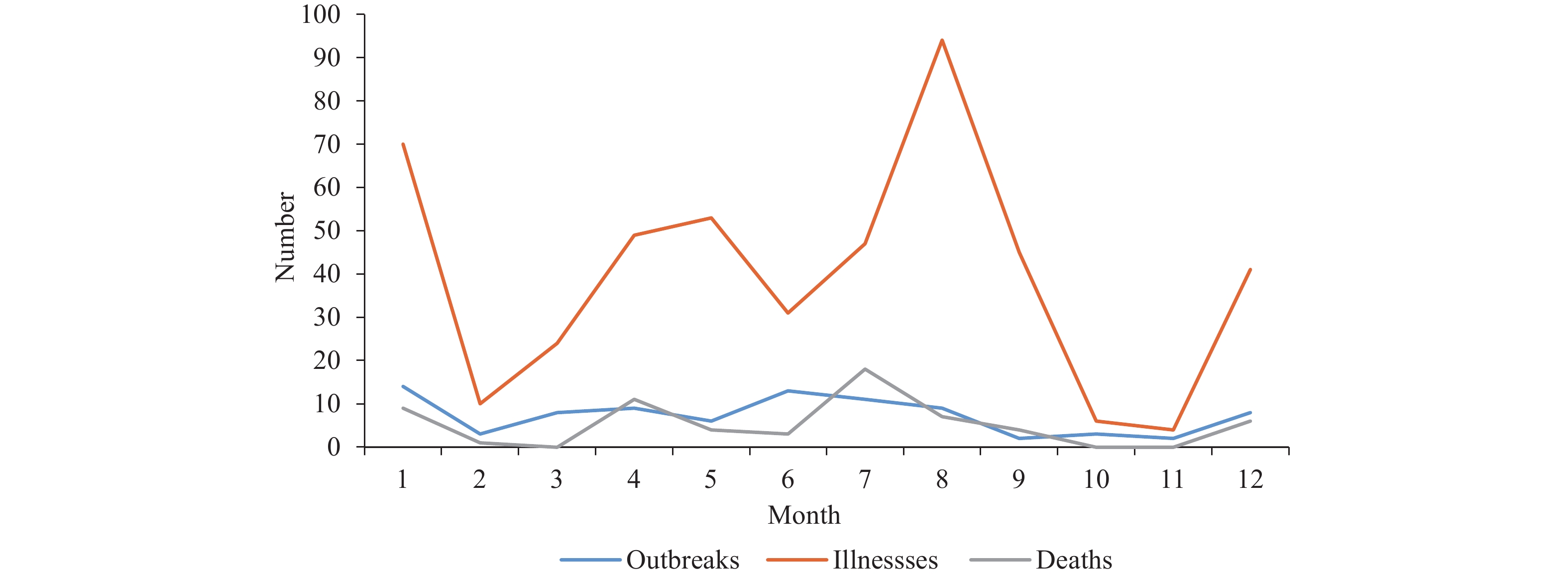

Nationwide, most cases were reported between June and August, but with a sharp peak in January (Figure 1). During 2004–2020, the mean annual number of outbreaks was 5 (range: 3 to 11 outbreaks). Xinjiang had the largest number of outbreaks (20), followed by Qinghai (13) (Qinghai accounted for the greatest number of illnesses (101, 26.17%) and deaths (18, 32.73%). Between the top two PLADs with the most outbreaks, there was no statistically significant difference in case fatality rate between Qinghai and Xinjiang (χ2=2.22, P>0.05). Among the 54 identified types of botulinum toxin, BoNT type A (28, 51.85%) was the most frequently identified toxin type, followed by type B (18, 33.33%). However, initial misdiagnosis occurred in 27.50% of cases (Table 1).

Table 2 shows that stinky tofu and dried beef were the primary sources of botulism, accounting for 41 out of 80 (51.25%) outbreaks in China. Among the top two foods with the most outbreaks, there was no statistically significant difference in case fatality rate between stinky tofu and dried beef (χ

2=1.61, P>0.50). Improper processing (32) and improper storage (30) were the main contributing factors of food-borne botulinum, accounting for 77.50% (62/80) of the total. Food types Contributing factors Total Improper processing Improper storage Raw material contamination Unknown etiology Stinky tofu 12 9 1 2 24 Dried beef 8 4 5 0 17 Soybean paste stew 6 1 2 0 9 Meat products 3 5 2 1 11 Tempeh 1 6 0 0 7 Mixed food 1 0 0 1 2 Homemade pickles 0 2 0 0 2 Soy products 0 2 0 0 2 Unknown etiology 1 1 0 4 6 Total 32 30 10 8 80 Table 2. Attribution analysis of food types and contributing factors of foodborne botulism, China, 2004–2020.

-

Foodborne botulism is an intoxication caused by ingestion of food containing botulinum neurotoxin. Cases of foodborne botulism are usually sporadic (single, unrelated), but outbreaks of two or more cases occur. Foodborne botulism remains a public health issue in China (5). From 2004 to 2020, the median number of outbreaks per year was 5 (range: 3 to 11 outbreaks). Whereas Xinjiang accounted for the highest number of outbreaks (20, 25.00%), Qinghai had the highest number of illnesses and deaths. This may be related to the fact that local farmers and herders especially in Xinjiang and Qinghai prepared traditional foods (home-made ethnic foods such as stinky tofu, soybean paste stew, and air-dried raw beef from households) using inappropriate/unsafe production processes (6); the study revealed that the primary cause of foodborne botulism was improper food handling practices and improper storage (55, 68.75%). For example, the fermentation process of home-made tempeh and soybean paste stew, etc. (placed in airtight containers) likely fostered an anaerobic environment, and suitable temperature (fermented for 10–15 days by the stove or radiator) was a necessary condition for toxin growth and production (7). Whereas some herders in Qinghai slaughtered cattle and sheep on the grass around their tents, put beef and mutton contaminated by botulinum toxin in the soil into pockets, and placed them outside the tent to air dry, the deeper part of the meat that was not completely air-dried still had some certain water content and the spores likely multiplied in the deeper part of the meat once the temperature was raised, providing conditions for the growth of botulinum toxin (8). Most reported cases mainly occurred from June to August in the study due to the high ambient temperature and high humidity at that time, which was compatible with the temperature required for botulinum to multiply and produce toxins. Our study highlighted the key characteristics of foodborne botulism outbreaks that could inform clinicians and public health officials in the development of preparedness and response plans (9). Therefore, targeted continuous education is needed to inform farmers and herdsmen in Xinjiang and Qinghai of the potential risks of botulism from ingesting homemade traditional native foods. It is necessary to standardize the management of processing, storage, and consumption of food raw materials. Preventive messages should focus on not using unsanitary and traditional food processing, changing the bad eating habits of eating raw or half-raw meat, heating and boiling native foods thoroughly to destroy toxins and prevent Clostridium botulinum poisoning.

Foodborne botulism is rare, thus some physicians are unfamiliar with the disease (10), and delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis potentially leads to severe fatal illness in clinical settings (11). Botulinum toxin poisoning has a high mortality rate of 14.25%, possibly related to the inability to diagnose correctly in time. In the study, initial misdiagnosis occurred in 27.50% of cases. Here, misdiagnosis means that patients with botulism can be misdiagnosed as having other illnesses, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome, common cold, malnutrition, and myasthenia gravis. Between the top two PLADs with the most outbreaks, the case fatality rate in Qinghai was higher than that in Xinjiang, which may be due to initial misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. Hospitals and provincial and local public health officials should incorporate stocking up on a certain amount of botulinum antitoxin into emergency planning. Professional prevention and treatment of food-borne botulism outbreaks should provide clinicians in hospitals with clinical, laboratory diagnosis and emergency preparedness precautions for botulism in the clinical guidelines to improve the recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of botulinum toxin poisoning; the need to rapidly identify patients in danger of respiratory failure must be anticipated (12). The provision of botulinum antitoxin should be ensured early and adequately used to avoid death.

We analyzed surveillance data from 50 outbreaks, and manual searches identified 30 publications of laboratory-confirmed outbreaks. They were merged and analyzed to make the data more representative and the analysis results more reliable. However, data elements were incomplete in much existing literature where clinical symptoms, incubation period, and some laboratories lacked the ability to differentiate between botulinum toxin and serum. Therefore, the epidemiological survey data and the quality of data reporting food-borne Clostridium botulinum surveillance should be improved; a better understanding of the epidemiology of botulism outbreaks can help tailor local prevention and public health response strategies.

This study is subject to certain limitations that may influence the generalizability of the findings. First, for many reported outbreaks, information on certain aspects of the outbreaks was missing or incomplete, so the conclusions might not be representative of unknown etiologies or food categories. Second, reported foodborne botulism outbreaks cannot represent all actual outbreaks occurred, since underreporting existed for various reasons, such as administrative intervention, insufficient ability of outbreak investigation, etc.

-

No conflicts of interest.

-

All members in all participating CDCs.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: