-

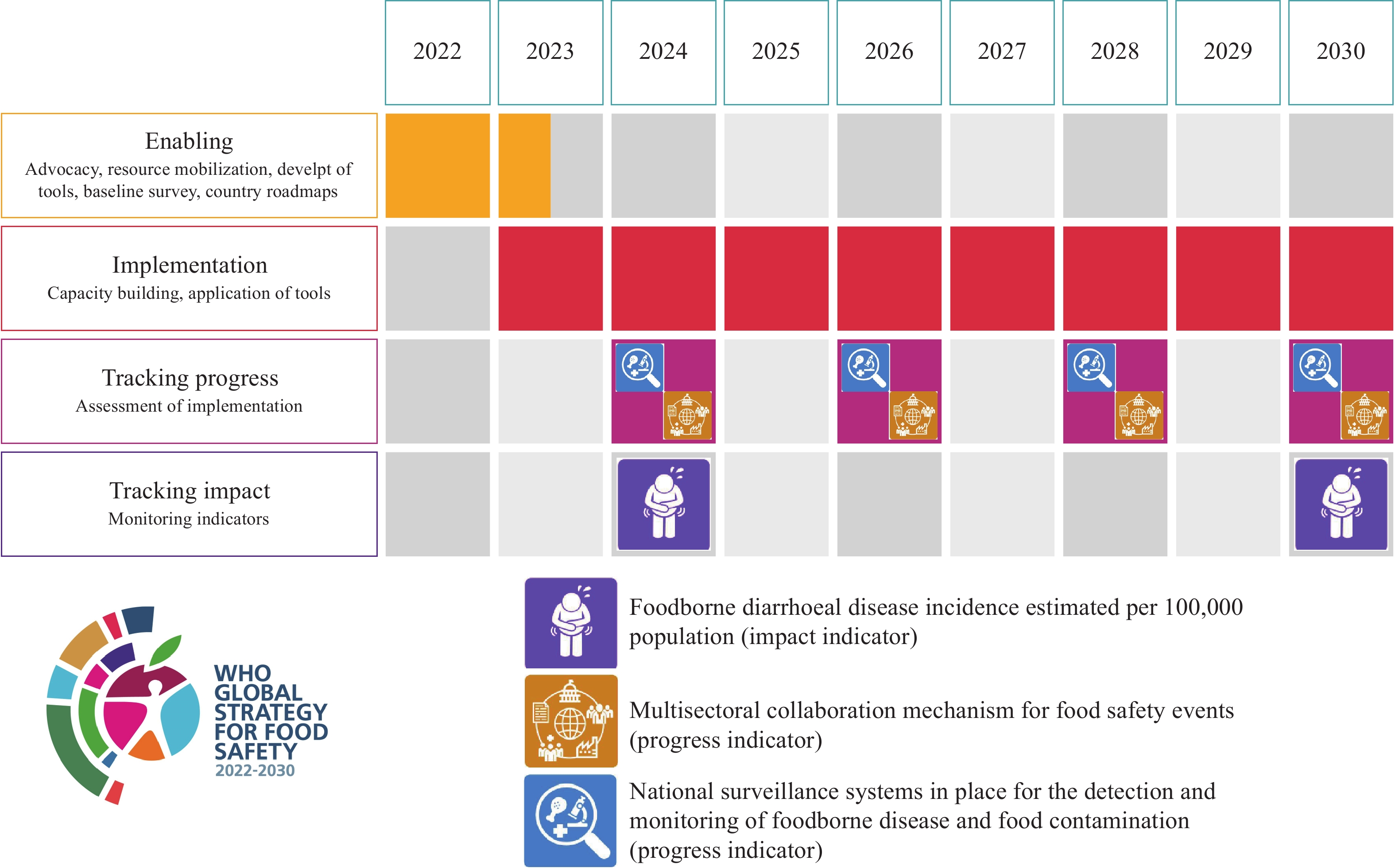

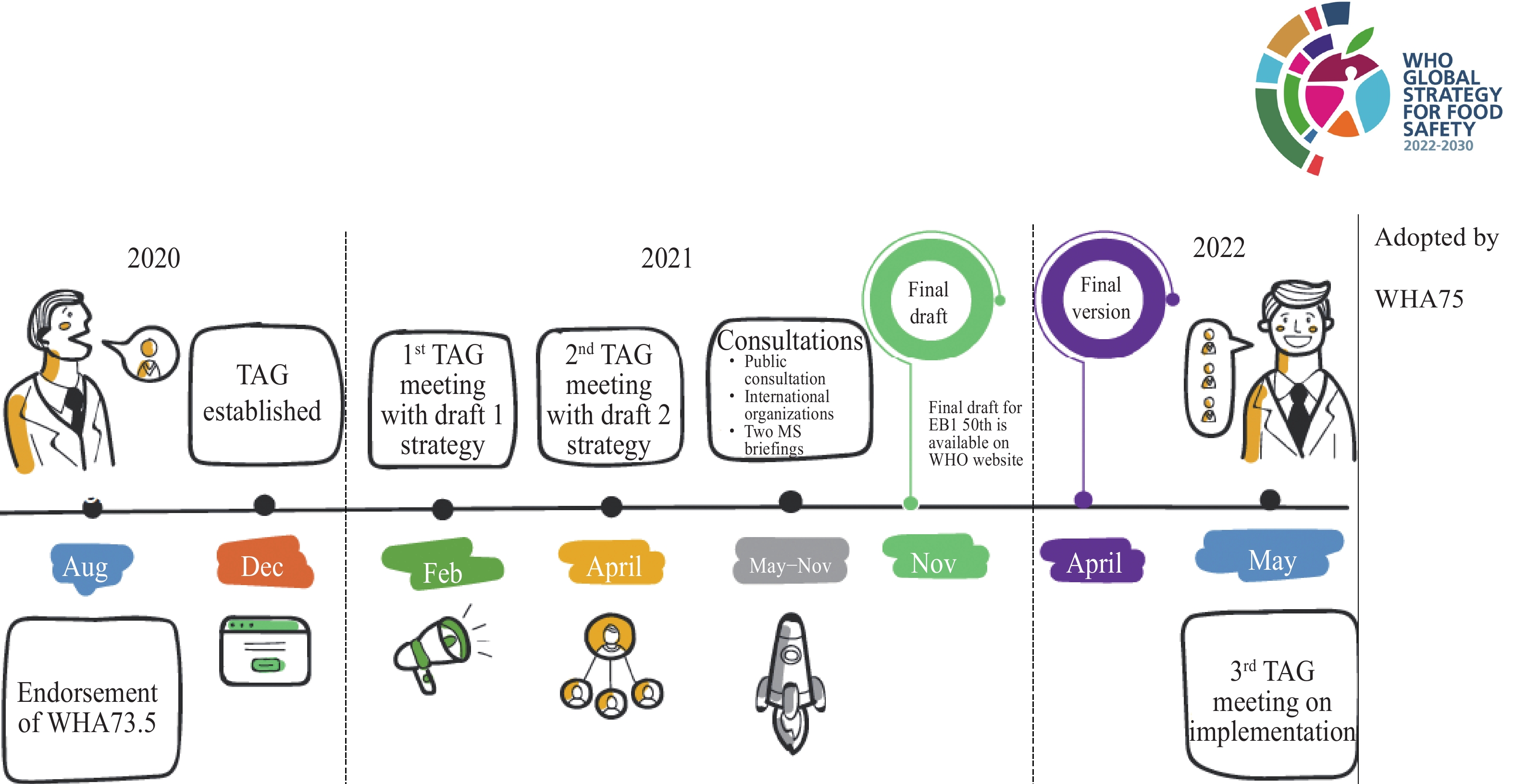

The Seventy-Fifth Session of World Health Assembly (75th WHA) has adopted the updated Global Strategy for Food Safety (2022–2030): towards stronger food safety system and global cooperation with the recommendations from the 150th Executive Board meeting (1-2). This response to the WHA 73.5 resolution on “Strengthening efforts on food safety” and Member States are requested to update GSFS to respond to current and emerging challenges. Developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) Secretariat with the advice of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Food Safety: Safer Food for Better Health (Figure 1), the vision of the updated strategy is to ensure that all people, everywhere, consume safe and healthy food to reduce the burden of foodborne diseases. The updated strategy aims to guide and support Member States in their efforts to prioritize, plan, implement, monitor, and regularly evaluate their actions towards reducing the burden of foodborne diseases by continuously strengthening food safety systems and promoting global cooperation. WHO will publish and translate the final document; develop guidance to assist Member States to implement the updated strategy and develop work plans (tools, investment case, map of stakeholders, baseline surveys, etc). It is important to have alignment between the Food Safety TAG and the Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group (FERG) in WHO for impact measurement. There is an opportunity to promote the updated strategy during the World Food Safety Day (WFSD) events celebrated annually on June 7. The theme of WFSD this year is “Safer food, better health” which is the same as the theme of the updated strategy. World Food Safety Day affords the opportunity to inspire global participation. The WFSD campaigns and the updated strategy stress the need to transform food systems to deliver better health in a sustainable manner in order to prevent most foodborne diseases.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.The overall process for the update of the WHO Global Strategy for Food Safety.

Notes: The TAG reffers to the technical advisory group on food safety: safety for better health in the World Health Organization.

Abbreviations: TAG=Technical Advisory Group; EB=Executive Board; WHO=World Health Organization; WHA=World Health Assembly; MS=Member States.

-

The 75th WHA has adopted the updated strategy with the recommendations from the 150th Executive Board meeting (1) as follows: to call on each Member State to develop a national roadmap of implementation and to make appropriate financial resources available to support such work; and to request the WHO Director-General to report back on progress in the updated strategy implementation to the 77th WHA in 2024 and thereafter every two years until 2030 (Figure 2). The implementation of the updated strategy will support the realization of food safety commitments emanating from the United Nations Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) convened as part of the Decade of Action to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. It will particularly support the WHO initiatives to support safe healthy diets, school meals, and One Health agendas.

Member States are at different stages regarding their national food safety systems and there is a need for a tailored approach to the implementation of the strategy. Adopting a One Health approach to food safety will allow Member States to detect, prevent and respond to emerging diseases at the human-animal-environment interface and to more effectively address food-related public health issues. The use of existing WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) tools and programs will support the implementation of the updated strategy and highlight areas where there is a need for new resources. The existing FAO/WHO Assessment Tool and FAO/WHO Diagnostic Tool (CTF) can be used to develop a baseline that will guide the GSFS implementation. Then TAG will update and detail the TAG work plan (2022–2023). The Member States can use the WHO Regional Advisors in the implementation of the updated strategy to assist in aligning with existing regional frameworks and identifying the regional priorities.

-

The China national strategy for food safety, proposed in 2016, marks the foundation of a unique Chinese framework in food safety management system with a core goal to ensure Chinese people “eat at ease and safely”. As a concrete response to the WHO updated GSFS, the Chinese government has proposed its own timetable and roadmap for its domestic food safety strategy which includes: 1) A zero tolerance of systemic food safety risks by 2020 and constantly improving the level of food safety assurance; 2) Establishing a strict, high-efficient, and socially governed food safety governance system by 2027; 3) Fundamentally achieving the modernization of food safety governance and oversight of the food chain by 2035; 4) Achieving universal modernization of food safety governance throughout China, and be one of the leading counties in the world for food safety standards and governance by 2050 (3).

WHO devolved the updated GSFS to guide and support Member States to prioritize, plan, implement, monitor and regularly evaluate actions towards the reduction of the incidence of foodborne diseases by continuously strengthening food safety systems and promoting global cooperation. The updated GSFS also reflects, and is complementary to, existing WHO health programmes, such as nutrition and non-communicable diseases (e.g., salt reduction), antimicrobial resistance, public health emergency and emerging diseases, climate change, environmental health, water and sanitation, and neglected tropical diseases.

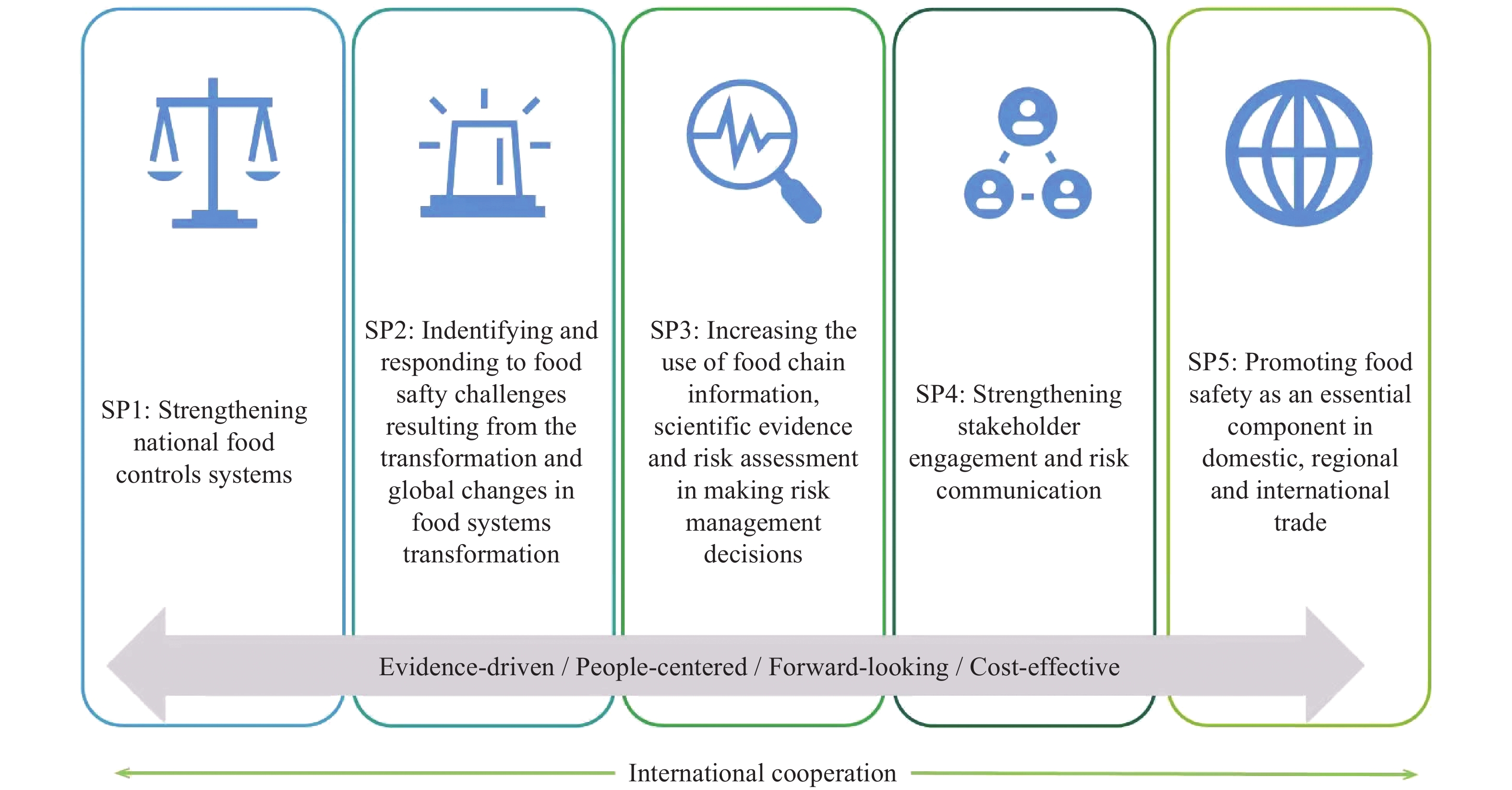

China will be an essential stakeholder in food safety to promote, support and protect public health and reduce the burden of foodborne diseases under the Healthy China framework. The updated WHO GSFS provides the five strategic priorities (SP) for concerted global action that will underline both the importance of food safety as a public health priority and the need to enhance its critical role as a public health component in food systems (Figure 3). Strengthening national food safety systems begins with establishing or improving infrastructure and components of food control systems as described in SP 1. For example, developing framework food legislation, standards and guidelines, laboratory capacity and surveillance, food control activities and programmes, and emergency preparedness capacity. In addition to establishing a national food control system, four important characteristics/principles are being considered and adopted for the system to be fully operational. Global targets and identifying indicators of success have been established, i.e., what gets measured gets done. In the case of the updated strategy, this means that regular measurement and reporting will keep a focus on priorities and objectives and will facilitate continuous improvement. Effective management of food control programmes involves monitoring to ensure proper implementation, efficient operation, and continuous improvement. Identifying expected outcomes and setting appropriate objectives which are communicated and being achieved, are all key to success. A part of the management of any programme is to select indicators and set targets to ensure progress. These simplify performance management by allowing all participants to understand not just their roles, but those of others. Indicators provide information about progress towards an objective and targets, and also support decision-making at all levels of an organization so that appropriate actions can be taken and remedial actions if required. Indicators are important for achieving the objectives of the national food safety systems because they keep the objectives at the centre of decision-making. The possible indicators are the followings: 1) Foodborne diarrheal disease incidence per 100,000 population; 2) Surveillance system in place for the detection and monitoring of foodborne disease and food contamination; 3) Multisectorial collaboration mechanism for food safety incidents.

Indicator 1 (foodborne diarrheal diseases) is an example of the health outcome indicator while Indicators 2 and 3 are process indicators. In setting targets and indicators, it is important to ensure that they are realistic and achievable. In China there is a lack of background data for disease burden of foodborne illness and foodborne diarrheal diseases. Enhanced Surveillance system and multi-sectorial coordination are now in place for the detection and monitoring of foodborne diseases and food contamination.

One of the challenges associated with using foodborne diarrheal disease as a health outcome indicator is that not all national surveillance systems are at the same stage of development. China sounded a word of caution about the interpretation of surveillance data, for example, the temptation of using the collected data to compare countries as this may be a reflection of the surveillance systems and laboratory capability rather than the true incidence and prevalence of the disease. TAG members suggested that foodborne disease outbreaks might be a better indicator to consider although there remain issues concerning comparability between countries due to differences in epidemiological investigative competencies and surveillance systems. The collection of data on the incidence of foodborne diarrheal disease is quite challenging, even for high-income countries. Additionally, using this indicator would overlook data on chemical contamination of food, which impacts diet-related diseases, such as cancer and chronic diseases.

It was also suggested to consider including sub-indicators under the main indicators. A sub-indicator could focus on countries’ testing capacity, for example, whether the country is testing for certain foodborne pathogens, etc. In this way, these sub-indicators can also be used to identify gaps within a country’s surveillance system, which, if addressed, could further strengthen their food safety capacity. It should be noted that the lack of capacity is the main bottleneck for setting indicators and targets. The sensitivity of trade implications highlighted by the indicators and targets could also be a reason that countries might be reluctant to report data to international organizations. The Global Foodborne Infections Network (GFN) is a very powerful resource to build countries’ capacity in foodborne diseases surveillance. Rather than looking at all foodborne pathogens, it might be good to focus at least initially on a few key foodborne pathogens, such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, etc. Another challenge is that the foodborne disease surveillance in many countries is managed by the health sector and there is no, or limited linkages, with food safety competent authorities and food testing laboratories. The challenge with setting targets is that there are limited baseline studies within countries, which means that the target-setting experience in the regions is very subjective. Another important issue is that countries have different capacities, so it might be more reasonable to set different targets for different countries or regions. The global strategy would require global targets. In the meantime, it should be possible to adapt global targets at regional and country levels. Setting global food safety indicators and targets within the strategy will encourage countries to invest more in their food safety systems and further strengthen their capacity.

China has made great advances in forensic microbiology, molecular diagnostics, surveillance systems and supporting IT infrastructure for both routine surveillance and early warning. Many of our initiatives are transferable to other member states and China can be a role model to help others. We live in a global village with food and ingredients globally distributed so the need for international co-operation has never been more important. No country can be complacent as often the safety of a Member State’s citizens is dependent on standards in another jurisdiction from where they import food. Nobody will be safe from food borne disease until we are all safe.

HTML

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: