-

The family planning policy has resulted in reduction of live births from 1982 and rapid economic growth in China (1). However, the pressure of the ageing, pension fund deficiencies, and increasing labor shortages has accelerated the announcement of the new adjusted family planning policy by the Chinese government, including a policy allowing couples in which at least one marital partners was an only-child to have two children in the end of 2013, and the implementation of a universal two-child policy in January 2016 (2). These adjustments were especially important for relatively developed urban areas because rural areas were subject to different policies since the 1980s (1). Therefore, we conducted this study based on surveillance data from 4 cities (Beijing, Wuhan, Chengdu, and Shenzhen) in China from 2014 to 2019. The study aimed to investigate the variations in the number of live births during 2013–2019 and the impact of new family planning policy on live births.

The data were collected from 3 continued surveillance projects from 2014–2019 that were founded by China-World Health Organization (WHO) Biennial Collaborative Projects entitled “Impact of the new family planning policy on maternal and children’s healthcare services” (2014–2015, 2016–2017) and “Surveillance of high-risk maternal health services and management” (2018–2019). These three surveillance projects were conducted to identify the number of live births and relevant maternal characteristics which may be influenced by changes in the family planning policy. All these projects were implemented by the National Center for Women and Children’s Health (NCWCH), China CDC.

In the surveillance, three cities including Chengdu, Wuhan, and Shenzhen were selected for the surveillance from the western, central, and eastern regions of China, respectively. The cities were selected based on their geographical location, their being likely to have been influenced by the policy due to having large population inflows and outflows, and an existing city-wide unified reporting system for maternal and newborn health. Furthermore, these criteria were used to select two districts (Haidian District and Chaoyang District) in Beijing Municipality to represent the northern region of China. Two districts were selected because Beijing had additional challenges due to an excessive number of midwifery institutions and special ministries, agencies, and military hospitals that made data collection much more difficult. The surveillance covered all health facilities providing childbirth services in the cities and included general hospitals, maternal and children’s healthcare hospitals, specialized hospitals, community health centers/township hospitals, and private hospitals. A total of 327 health facilities from 48 counties in the 4 cities were covered in the surveillance.

The maternal and child health (MCH) information system covering the whole city was available in each city, and individual information for all pregnant women who attended antenatal care and delivery in the four monitoring areas were recorded in the system. Our study collected all surveillance information based on the system routinely in each quarter of each year, including the total number of live births (2013–2019). During 2014–2017, if the woman or her husband was an only-child and the couple gave birth to their second child between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2015, or the woman who gave birth to her second child on or after January 1, 2016, the second child was then classified as a live birth in accordance with the new family planning policy (abbreviated as “policy-related live birth”). Trained medical workers enquired and made sure whether the pregnancy or delivery was in accordance with the new family planning policy in the following two time points: 1) during the pregnancy when the information of the mother was recorded in the maternal and child care handbook or medical record for antenatal care; and 2) after childbirth. After 2017, policy-related live births were not recorded due to the likely stable implementation of the new family planning policy.

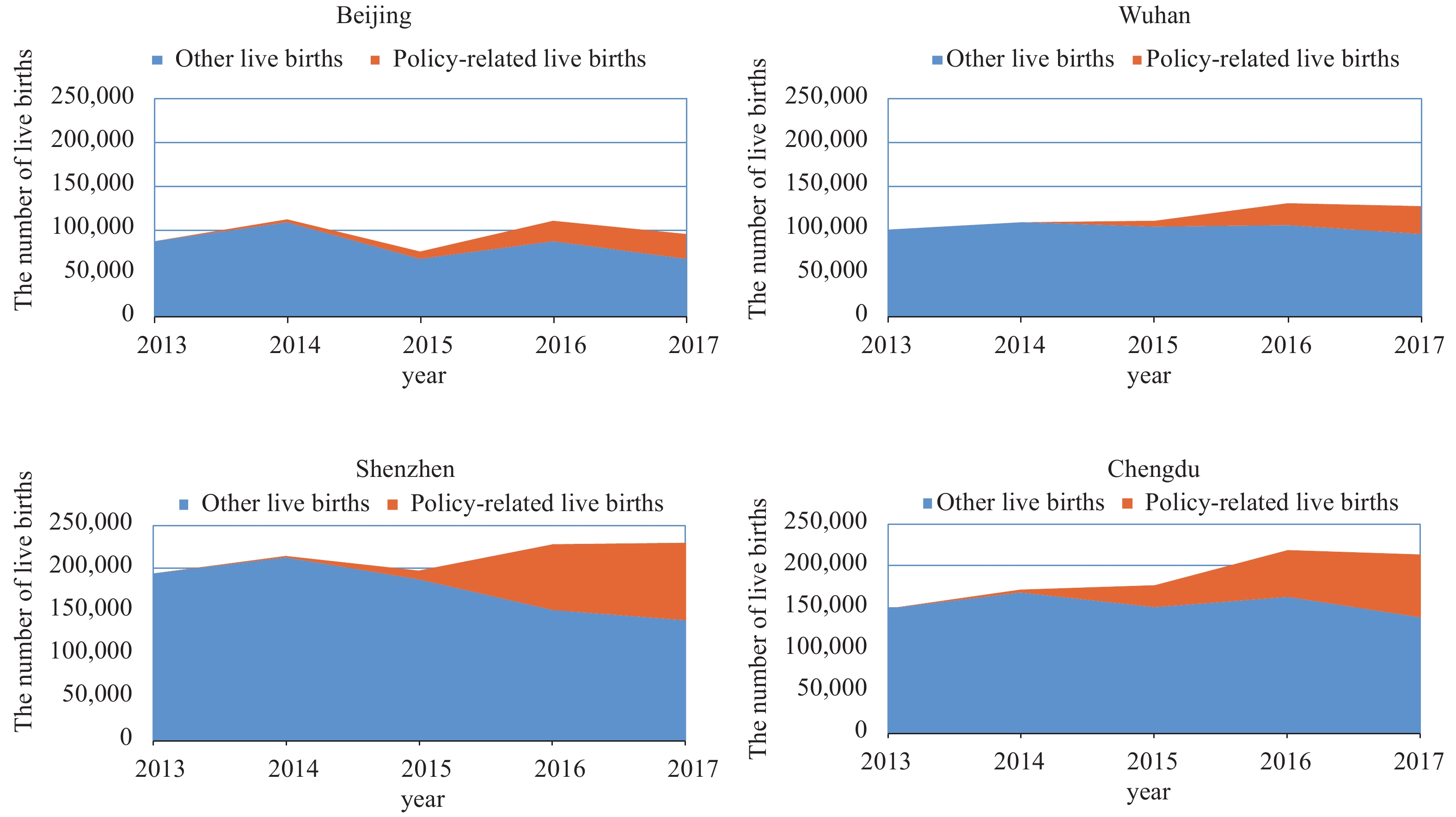

Because of different city characteristics, population characteristics, and crude birth rates, significant variation was found in the total number of live births in the four cities. Shenzhen had the largest number of live births each year, and the second was Chengdu. For Beijing, only two districts were included in the surveillance, and the number of live births was the smallest. Compared with 2013, the number of live births in Chengdu increased significantly with the change in rate being between 14.7% to 46.6% and remaining largely stable after the peak period in 2016. Although the increase in the number of live births in Wuhan from 2014 to 2019 was lower than that in Chengdu, it also remained basically stable after the peak period in 2016. The peak number of live births in Shenzhen was in 2016 and 2017, and the change rate of live births declined after 2018. Compared with 2013, the number of live births in the two monitoring districts in Beijing increased significantly in 2014 and 2016, with a nearly 30.0% increase, but declined in other years especially in 2015 where the change in rate was -14.4%. The details were shown in Table 1.

Cities 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Average from 2014 to 2019 Beijing Live births 86,938 112,854 74,457 111,142 95,409 84,259 86,040 94,027 Change rate (%) ref 29.8 −14.4 27.8 9.7 −3.1 −1.0 8.2 Wuhan Live births 99,493 109,304 109,855 130,334 127,512 120,726 120,191 119,654 Change rate (%) ref 9.9 10.4 31.0 28.2 21.3 20.8 20.3 Chengdu Live births 149,695 171,637 177,553 219,460 213,616 195,197 217,107 199,095 Change rate (%) ref 14.7 18.6 46.6 42.7 30.4 45.0 33.0 Shenzhen Live births 194,010 214,826 197,679 227,876 230,449 207,323 210,699 214,809 Change rate (%) ref 10.7 1.9 17.5 18.8 6.9 8.6 10.7 All Live births 530,136 608,621 559,544 688,812 666,986 607,505 634,037 627,585 Change rate (%) ref 14.8 5.5 29.9 25.8 14.6 19.6 18.4 Table 1. Number of live births from 2013 to 2019 and change rate (%) in the four monitoring cities.

In the 4 cities, the total number of the policy-related live births increased each year from 2014 to 2017, and the overall proportion of policy-related live births reached 33.9% in 2017. Among the four cities from 2014 to 2017, Shenzhen had the largest proportion of policy-related live births (0.6% to 39.4%), followed by Chengdu (2.0% to 35.0%) and Beijing (3.1% to 30.2%), while Wuhan had the comparatively smallest proportion (1.0% to 25.1%). The number and the proportion of policy-related live births in each city were shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Cities 2014 2015 2016 2017 n % n % n % n % Beijing 3,542 3.1 7,056 9.5 23,530 21.2 28,783 30.2 Wuhan 1,090 1.0 5,718 5.2 24,822 19.0 31,953 25.1 Shenzhen 1,374 0.6 10,852 5.5 76,593 33.6 90,721 39.4 Chengdu 3,502 2.0 27,043 15.2 57,107 26.0 74,724 35.0 All 9,508 1.6 50,669 7.4 182,052 26.4 226,181 33.9 Table 2. Number and proportion (%) of total live births that were policy related in the four monitoring cities from 2014 to 2017.

HTML

-

To our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the proportion of policy-related live births in more developed areas of China. Our results showed that the number of live births in the four cities has increased overall since 2014, which was especially evident after the universal two-child policy in 2016. The change in the number of live births showed that the implementation of the newly adjusted family planning policy alleviated the decreases in the total number of live births and started increasing. The cities were located in four relatively developed cities whose provinces also showed a similar pattern of growth in the number of live births according to the national report (3-4). Our results confirmed the previous prediction of the slow growth of total live birth rates in China, and the newly adjusted family planning policy will therefore not result in a baby boom (2). We could foresee that the new policy will be conducive to a rebound in the number of live births and to alleviating the population crisis. The increased proportion of policy-related live births also showed that the implementation of universal two-child policy resulted in more decisions from couples to have a second child.

Our findings suggested that the newly adjusted family planning policy was a highly desirable action that will be beneficial for population size and low fertility in China, and it was likely to remove some oppressive elements of the previous policy (1-2). However, this increase will create new challenges in the field of obstetrics, neonatology, and related health facilities. It should be noted that the preconception health risks, pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes increased with age (5). From 2015 to 2018, the proportion of newborns delivered by older females (35 years and above) increased year by year, reaching its peak in 2017 (13.4%) (6). The proportion of older females in our study was similar to this estimate, but much higher in women who gave birth to their second child. Methods for dealing with these challenges for mothers with their second child should be developed as experience in addressing this issue is lacking. The health facilities in China should develop more sophisticated prenatal, peripartum, and neonatal healthcare to overcome this challenge (7).

This study was subject to some limitations. First, the surveillance data were collected in four relatively developed cities of China, so the results maybe not suitable to explain the policy effect to the selected regions or nationally in China. Second, rural areas may be subject to significantly different conditions due to differences in policy and traditional expectations. Nevertheless, future studies should also focus on remote, rural areas because of the higher caesarean delivery rate and the more advanced ages of the mothers, which may have further value for the policy makers.

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: