-

Since the outbreak of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in three countries in West Africa, China CDC has conducted two phases of technical cooperation projects based on the Sierra Leone-China Friendship Biological Safety Laboratory (SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab) in the Republic of Sierra Leone (1-2). Phase I was conducted from July 2015 to June 2017, while Phase II started in July 2017 and will continue to June 2020. In total, 85 Chinese public health specialists have been dispatched to Freetown, the capital city of Sierra Leone, with 80 serving for 6 months and 5 serving for a year. Most Chinese staff came from China CDC and the remaining roughly 15% came from different provincial-level CDCs. This report summarizes major developments to Sierra Leone’s public health field and comments on experiences obtained from the joint effort.

HTML

-

The collaboration between China CDC and the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (Sierra Leone MoHS) has yielded several major developments to help confront infectious disease threats.

First, the local laboratory capacity for determining pathogens was greatly increased. Before the outbreak of EVD, only a few pathogens could be determined via laboratory tests in Sierra Leone, such as malaria, Lassa fever, HIV, tuberculosis (TB), and hepatitis B virus (HBV). Some other diseases, such as Marburg virus disease and Monkeypox, needed to be diagnosed in labs in other countries, usually receiving feedback months later. Since a SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab was established, the methodologies to determine Ebola virus, malaria, and more than 24 various viruses and 10 bacteria were established. Those remarkably increased the laboratory diagnostic capacity for infectious diseases in Sierra Leone.

Second, following the EVD outbreak, SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab was conferred as the national reference laboratory for viral hemorrhagic fevers, which has helped ensure health security. More than 200 specimens from patients suspected as Ebola or other fatal hemorrhagic fever were submitted by the Sierra Leone MoHS for diagnosis or distinguishing diagnosis since the beginning of Phase II. Among them, 106 samples were tested between July 2018 and June 2019. All specimens were tested immediately in SLE-CHN BSL-3 laboratory and the results were returned within 12 hours. No Ebola virus was detected, whereas two cases of Monkeypox were identified by the real-time PCR (RT-PCR) assays. Those two cases of Monkeypox were the fourth and fifth cases to appear since the initial case of Monkeypox in Sierra Leone (3). Moreover, the positive results of RT-PCR for Monkeypox were confirmed using Nanopore DNA sequencing assays. This irreplaceable laboratory capacity significantly enhanced the emergency response capability of Sierra Leone for public health events. The capacity of the SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab was also highly recognized and praised by local colleagues and Sierra Leone MoHS.

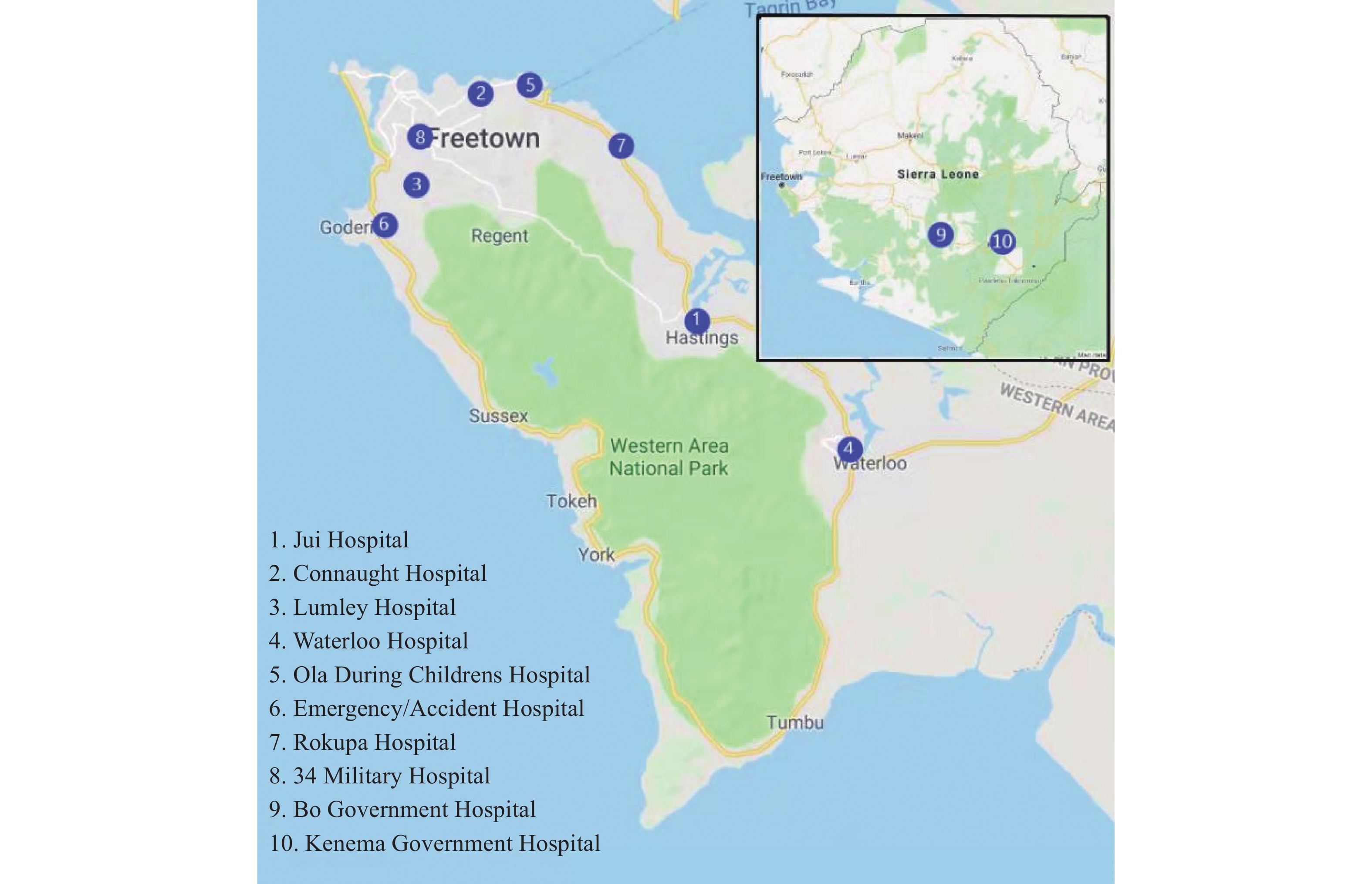

Third, several active pathogenic surveillance networks were established, including surveillance for patients with fever, surveillance for patients with bacterial diarrhea, environmental surveillance for mosquitos, and environmental surveillance for water. The surveillance networks covered Freetown, Bo, and Kenema with 10 sentinel hospitals (Figure 1). Collected samples and information sheets were transferred to the laboratory once a week. The main detecting pathogens in the surveillance networks for patients with fever were Ebola, Lassa fever, Marburg, Rift Valley Fever, Chikungunya, Dengue, Zika and Yellow fever viruses, while the bacterial pathogens in the surveillance for diarrhea were Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Salmonella, Shigella, and diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC).

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Distribution of 10 sentinel hospitals for syndromic surveillance of patients with fever or bacterial diarrhea.

More than 9,000 serum samples were collected and roughly 17,000 tests of RT-PCR were performed during Phase II so far. Outside of five positive samples of Lassa fever virus collected from Kenema, no other fatal viruses were detected from those serum samples. Between January and June of 2019, 3,791 serum samples were tested with malaria rapid detecting technique. The positive rate of malaria in outpatients with fever was 16.2% (614/3,791), in which the positive rate in Freetown was 16.1% (416/2,586), in Bo was 19.8% (137/692), and in Kenema was 11.9% (61/513). A total of 65 stool samples were collected from the patients with diarrhea and bacteria cultures were performed. A total of 2 strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, 10 strains of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (4 strains of enterotoxin of DEC, 2 strains of enteroinvasive E. coli, 4 strains of enteroaggregative E. coli) were isolated. No Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella, Shigella were isolated from the stool samples. One strain of Salmonella was isolated from the blood sample of a fever patient.

Fourth, public health personnel capacity was improved. Since the implementation of Phase I in July 2015, multiple training courses had been conducted in Sierra Leone, which covered a broad range of preventive and clinical medicines, such as leading capacity, control and prevention for infectious diseases, clinical management for infectious diseases, emergency response for public health events, malaria control, molecular diagnosis, pathogen determination, and identification and diagnosis techniques for many special infectious diseases. At the National Training Center for Biosafety, several training courses of biosafety and biosecurity, laboratory management and quality control also had been conducted. A total of 356 Sierra Leone professionals attended the various training courses.

In total, 12 young Sierra Leone professionals have worked in SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab, and 3 of them have received scholarships for master or doctoral programs. Most of them joined the SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab without any experience for laboratory. Through attending various training courses, particularly in-person training and daily laboratory work, several young staff have already mastered operating skills for BSL-2 laboratories, with some mastering even BSL-3 laboratory skills, as well as principles for laboratory biosafety and management.

Finally, the collaboration between China and Sierra Leone yielded a platform for international communication and cooperation. Several international collaborating studies were conducted, such as an evaluation of the rapid diagnostic test for Ebola virus and for Ebola RNA persistence in semen from survivors (4). In addition, comprehensive discussions and communications are carried out with various international organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) Sierra Leone Office, World Bank, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), US CDC, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), European Research Council, Department for International Development (DFID) UK, and German Agency for International Cooperation.

Two separate international workshops were held in Freetown at the end of 2018, which were sponsored by China CDC and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. One workshop focused on the birth dose for HBV vaccination, and the other focused on malaria control and prevention. Dozens of specialists from China CDC, WHO, WHO-AFRO, Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), US CDC and other African countries participated in the meetings. Strategies and techniques for control of HBV and malaria as well as possible future opportunities for collaboration were deeply discussed.

-

Infectious diseases, particularly emerging infectious diseases, should be the highest priority as they directly affect global health security. In the past 15 years after the severe acute respiratory syndromes (SARS) outbreak, numerous emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases have caused regional or global concerns, such as Ebola, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), pandemic influenza, and Zika. Review of the emergence of new infectious diseases in China in the past years also illustrates that the majority are imported cases, e.g., poliovirus (wild-type) in 2011 (5), MERS in 2015 (6), Zika in 2016 (7), and yellow fever in 2016 (8). Control and prevention of cross-border transmission, especially long-distance transmission of infectious diseases, became one of the most important topics for global health security.

Besides Ebola, many other fatal infectious diseases including Marburg fever, Lassa fever, Yellow fever, Monkeypox, and Cholera, continually threaten regional and global health security (9-10). Timely identification, recognition and determination of the pathogens, and proper and efficient implementation of local response measures are critical for any outbreak of infectious disease that has potential to spread regionally and globally. Therefore, increasing the capacity of rapid response to emerging infectious diseases in each country in the African continent is crucial for global health security.

In addition to emerging infectious diseases, other traditional infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, and respiratory TB are still major public health problems and have high disease burdens in many African countries. According to WHO, over 61% of global HIV-related mortality is found in Africa in 2018 (11), while that of malaria is approximately 93% (12). Lack of nutrition, environmental pollution, and safe water supply are also recurring issues. Although these challenges are improving due to concerted effort from the international community, the problems are still far from being solved. Improving the efficiency and effectiveness of future China-Africa cooperation is also a major challenge for Chinese public health staff.

Cooperative projects in public health also require an in-dept understanding of local circumstances and requirements. Proper communication and adjustments can ensure the smooth implementation of surveillance projects, though further improvements in sensitivity and quality still need to be made for many of these systems. Furthermore, involving local staff provides several advantages as many Chinese public health staff benefitted from collaborating with local colleagues to overcome language barriers, to communicate knowledge of local culture and circumstances, and offer invaluable suggestions and comments.

China is still a relatively young partner as involvement in the field of global health was prioritized relatively recently (13). Many aspects of global health collaboration remain to be learned and to be adjusted to, and active communication with international partners will benefit mutual understanding and cooperation. China CDC will continually focus on public health cooperation with African countries to strengthen their public health system and the capabilities of African public health personnel with the aim of supporting African countries to achieve the African Union 2063 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

-

We thank all Chinese specialists having worked in Sierra Leone for implementation of those projects, particularly Drs Wenbo Xu, Jun Liu, Yong Zhang, Jingdong Song, Ning Xiao, Biao Kan, and Zhaojun Duan as the team leaders. We also appreciate the Sierra Leonean staff for their wonderful work in SLE-CHN BSL-3 Lab and China CDC teams.

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: