-

The centenary of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic is a time to evaluate preparedness for the next pandemic. In 1918, the pandemic spread across the world in three waves, causing an estimated 20–100 million excess deaths (1). Almost 100 years later, China experienced its largest, most widespread epidemic of human infections with avian influenza A (H7N9), the influenza virus with greatest pandemic potential of all viruses assessed to date by United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (U.S. CDC) Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (2). This historical review describes China’s developments in the field of influenza over the past century and asks, what are China’s strengths and remaining challenges in pandemic preparedness today?

-

In 1918, local newspapers, commercial trade and post office reports first described outbreaks of respiratory illness in China in the southern port cities of Guangzhou and Shanghai. A well-circulated Shanghai daily newspaper published epidemic reports and severe outbreak alerts in early June, announcing the closure of public facilities such as cinemas. At the time, the Republic of China’s limited public health capacity was further hampered by political instability, and by December 1918, the pandemic had spread to northeastern provinces. In rural villages, people reportedly suffered fever, cough and muscle pain and died within days. The illness, called ‘bone pain plague’, ‘five-day plague’, and ‘wind plague’ due its severity and transmissibility, caused a shortage of coffins. Villagers sprayed limewater on their roofs to prevent infection, and they used traditional Chinese herbs for treatment (3). The pandemic continued until early 1919, when the first national public health agency, the “Central Epidemic Control Division”, was established in June 1919. Although Chinese mortality data are limited, an estimated 4-9.5 million died from this pandemic (4).

Due to extensive research following the 1918 pandemic, the United Kingdom isolated the first influenza virus [A(H1N1)] in 1933 and the U.S. developed the first influenza vaccine in 1935.

-

When the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was founded in 1949, the central government funded and operated the country’s healthcare system. In 1952, the PRC initiated influenza surveillance and founded its first influenza epidemiology office and laboratory in 1954.

-

An influenza outbreak detected in Guizhou Province, southwest China, in February 1957 spread to Hong Kong,China in April, resulting in 250,000 cases (5) and to Japan and Singapore in May. This pandemic of influenza A(H2N2), known as “Asian flu”, caused an estimated 1–4 million deaths globally (6–7) and became the most severe influenza epidemic recorded in China since the establishment of the PRC. The identification of clusters of sick students prompted several provinces to close public facilities, including schools and cinemas. Although health agencies disseminated influenza prevention messages by newspaper and radio, treatment of infected persons was limited by shortages of medicine. A second pandemic wave spread across China in the latter half of 1957, prompting the government to establish the Chinese National Influenza Center (CNIC) to lead influenza control efforts.

The World Health Organization (WHO) launched the global influenza program in 1947 and established the Global Influenza Surveillance Network (GISN) in 1952. The 1957 pandemic was the first influenza pandemic detected by GISN and occurred before the PRC was a WHO member state.

-

The 1968 pandemic virus, influenza A(H3N2), was first isolated in Hong Kong, China in July after a sudden increase of influenza-like illness (ILI) which affected approximately 15% of Hong Kong’s population (8). The epidemic spread rapidly to India and the Northern Territory of Australia and then to other northern hemisphere countries during the winter of 1968–1969 causing an estimated 1–4 million excess deaths worldwide (7). During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), most public health data collection in China was suspended; however, reports from CNIC’s outpatient ILI surveillance sites in Guangdong, Sichuan, Shanghai, Beijing, Harbin, and Qingdao, suggest that the highest annual number of laboratory-confirmed ILI cases in China during 1968–1992 occurred in 1968 (9).

-

After becoming a WHO member country in 1972, China invested resources in CNIC’s research infrastructure and formed international collaborations to strengthen influenza surveillance.

In 1981, China joined the WHO’s GISN, now called the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). In 1988, China initiated influenza laboratory capacity building programs supported by international partners including WHO and U.S. CDC. Since the 1990s, CNIC has sent more than 4,000 circulating and candidate seasonal influenza vaccine viral strains to WHO Collaborating Centers. In 2000, with WHO support, China expanded its influenza surveillance network with more sites.

-

In January 2002, the Chinese Academy of Preventive Medicine that housed CNIC was renamed the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). Later that year, Guangdong Province reported the first cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), which became an outbreak of international concern in early 2003. As a result, China invested in a nationwide network of CDCs at the national, provincial, prefecture and county levels and in April 2004, launched a real-time web-based reporting system for notifiable infectious diseases and emerging public health events to connect 100% of CDCs at all levels and 98% of national, provincial and prefecture health facilities. In the same year, China identified highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in numerous poultry outbreaks and several human infections (10). Early detection of respiratory infectious diseases, including SARS, H5N1 and other novel avian influenza viruses, became a public health priority in China. By 2005, CNIC had further expanded its national influenza surveillance network to all 31 provinces with 63 network laboratories and 197 sentinel hospitals.

-

In April 2009, after a surge of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 cases was reported from Mexico and the United States, WHO declared a public health emergency of international concern. China first responded with a policy of containment and quarantined foreign travelers and persons with respiratory symptoms in hospitals. After five months, the focus of response shifted to active surveillance for influenza cases (11). WHO officials praised China for its transparent response and success in mitigating the outbreak. An estimated 32,500 (95% Confidence Interval 14,000-72,000) of the 100,000-400,000 estimated global excess respiratory deaths occurred in China (12-13).

The 2009 pandemic triggered further government investment in China’s influenza surveillance network, which, by the end of 2009 included 411 laboratories and 556 sentinel hospitals, one of the largest influenza surveillance networks in the world.

-

In October 2010 CNIC was designated as the fifth and latest WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza. CNIC’s surveillance network collects 200,000–400,000 specimens and conducts antigenic analysis on approximately 20,000 viral strains annually. In addition, CNIC disseminates a weekly, online influenza surveillance report in Chinese and English, reports data on ILI, circulating influenza subtypes and the novel influenza virus detections to WHO, and provides training to influenza centers in neighboring countries.

-

In March 2013, Shanghai Municipality and Anhui Province sent CNIC three human specimens of unsubtypable influenza from patients critically ill with pneumonia. The specimens tested positive for influenza A/H7 and were identified as low pathogenic (causing mild or no symptoms in infected poultry) avian influenza (LPAI) A(H7N9) (14). CNIC reported the first three cases of human infection with novel H7N9 virus to WHO within one week of isolation and sequencing and shared the virus with other WHO Collaborating Centers within 7 weeks. From 2013–2017, China has experienced annual epidemics of human infections with H7N9, with a cumulative 1,537 human cases identified through September 2019. The fifth H7N9 epidemic from October 2016–September 2017 was notable for a surge in cases (n=758), wide geographic spread throughout China (27 of 31 provinces affected), and the first detection of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H7N9, a virus that causes severe disease in poultry in addition to humans (15). Although no sustained human-to-human transmission of H7N9 has been reported to date, both LPAI and HPAI H7N9 infection in humans are associated with severe illness and high mortality (approximately 40%).

Because most (90%) humans infected with avian influenza A(H7N9) have been exposed to live poultry within the two weeks preceding illness onset, China initiated poultry industry reform, including banning live poultry markets in major cities and promoting market sanitation. The animal health sector, led by the Ministry of Agriculture, became increasingly engaged in H7N9 detection in poultry after the emergence of HPAI H7N9 in early 2017. In September 2017, the Ministry of Agriculture initiated a nationwide poultry vaccination campaign with bivalent H5/H7 poultry vaccine. Since that time, only 5 cases of H7N9 human infection have been reported.

-

China was affected by all four pandemics in the past century and the 1957 and 1968 pandemics were first identified in China (Table 1). The virus with the highest pandemic potential to date among all influenza viruses assessed, avian influenza A(H7N9), was also identified in China. With 20% of the world’s population and the world’s largest poultry production of 5 billion chickens and ducks per year, China plays a critical role in global influenza pandemic preparedness through continuous surveillance for early detection of novel viruses.

Pandemic Influenza A Virus Subtype Area of First Detection Estimated Mortality Worldwide Estimated Mortality in China Population in China 1918 H1N1 Unclear 20-100 million(1) 4-9.5 million(4) 460 million 1957 H2N2 Southern China Singapore/Hong Kong, China 1-4 million(7) 225,000-900,000* 646 million 1968 H3N2 Hong Kong, China 1-4 million(7) 220,000-881,000* 782 million 2009 H1N1pdm09 North America 100,000-400,000(13) 32,500(12) 1.33 billion * No published data available; mortality estimates in China for pandemics in 1957 and 1968 were extrapolated by multiplying the global mortality estimates and the proportions of China’s population size in the world. Table 1. Estimated mortality of the past influenza pandemics.

-

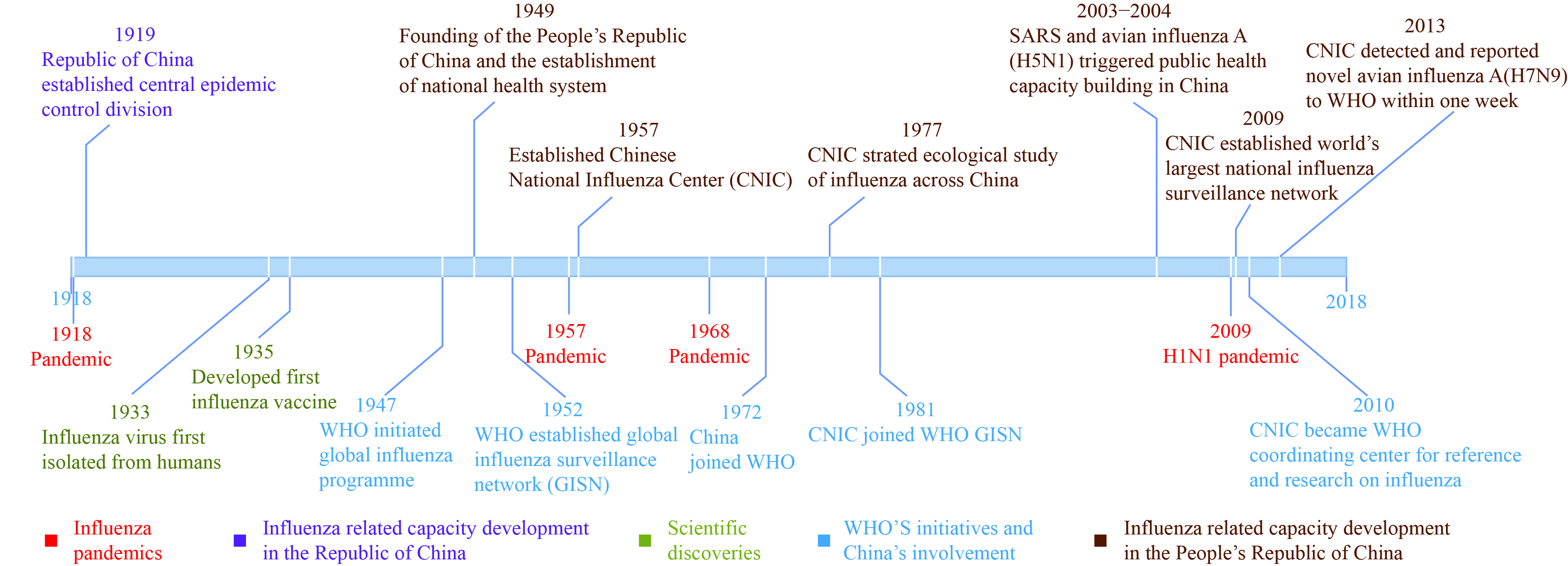

In the past several decades, China has made significant progress in responding to influenza pandemics through public health investment and infrastructure development resulting in an influenza surveillance network covering most of the nation (Figure 1). China’s response to the H7N9 epidemics was notable for close public health collaborations with WHO and other international organizations in regular, joint risk assessments to enable the timely dissemination of data to the international community. Additionally, China has demonstrated interest in coordinating surveillance and response efforts with regional partners, and it has the capacity to implement sweeping measures with central government support, such as mass poultry vaccination.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.Influenza pandemics, scientific discoveries and China’s influenza-related capacity milestones, 1918–2018.

Despite these advances, key challenges remain. Using WHO’s “Checklist for Pandemic Influenza Risk and Impact Management” and U.S. CDC’s “Preparedness and Response Framework for Influenza Pandemics”, China CDC influenza experts summarized recent progress, remaining challenges and proposed actions in five core components of pandemic preparedness (Table 2).

Subject Remaining Challenges Planned Actions Political Commitment - Underinvestment in CDC human resources contributing to difficulties in recruiting and retaining highly qualified public health professionals

- Inadequate emphasis on pandemic preparedness at higher government levels due to competing health priorities- Increase financial investment in the public health system in China particularly with respect to recruiting and retaining highly qualified public health professionals

- Prioritize pandemic preparedness and develop an updated national influenza pandemic preparedness planMultisector Coordination - Inconsistent data sharing between animal and human health sectors

- Insufficient communication between clinicians and public health professionals- Convene regular multi-sectoral systematic planning meetings during inter-pandemic periods to promote a One Health approach to influenza

- Disseminate key public health messages to clinicians through multiple approaches (e.g., medical education; continuing education; social media)

- Develop mechanism for clinicians to communicate with public health professionals (e.g., clinician hotlines; conferences on cross-cutting topics for both public health professionals and clinicians)Influenza Vaccination - Significant underuse in all high-risk groups

- Inadequate awareness of the influenza vaccine in both health care workers and the public- Conduct mass media campaigns and continuing education to increase awareness of influenza vaccine in both health care workers and the public

- Develop strategies to increase influenza vaccination in health care workers

- Develop strategies to encourage health care workers to recommend seasonal influenza vaccine to high risk patients

- Expand adult immunization services

- Develop free influenza vaccination policy for high risk groups

○ Explore whether insurance can be used to pay for the influenza vaccine for the general publicMedical Care and Countermeasures - Insufficient healthcare surge capacity

○ In the 2017-18 influenza season there were:

● Temporary antiviral shortages

● Hospitals overrun with patients

● Too few ventilators

- Insufficient knowledge of how to prevent, test for and treat seasonal influenza illness, including lack of knowledge about hospital acquired infections- Improve infrastructure and operational standards at all hospital levels

- Improve preparedness and continuity of clinical capacity at all levels (through regular training, continuing education etc.)

- Implement early warning systems and develop plans for taskforce management to respond to unexpected surges in healthcare utilization during the influenza season

- Improve clinical practice for seasonal influenza prevention, testing and treatment (through regular training, continuing education etc.)

- Promote vaccination and PPE among healthcare workersRisk Communication - Lack of an official technical framework to communicate seasonal influenza intensity, severity and risks - Develop an influenza intensity and severity framework based on data collected in recent influenza seasons Table 2. Remaining challenges and recommended actions for influenza pandemic preparedness in China.

-

After the 2003 SARS outbreak, recent avian influenza outbreaks and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, China increased political commitment and financial resources for preventing infectious diseases, enhancing influenza surveillance and response capacity, and expanding the CDC system. As of November 2017, China CDC consisted of 3,481 units and 877,000 public health professionals serving at all levels of government. In addition, a web-based national notifiable infectious disease reporting system was developed to increase timely case reporting.

Nevertheless, growing public health needs have stretched the still limited investments in China’s public health system. Low salaries are a significant barrier to the recruitment and retention of high quality professionals, and recently, CDC staffing at all levels has declined. In addition, competing health priorities potentially interfere with high level Chinese government commitment to pandemic preparedness. Improved CDC human resource development is essential, in addition to the government’s prompt endorsement of an updated national influenza pandemic preparedness plan.

-

As demonstrated during the recent H7N9 epidemics, China has the capacity to implement sweeping measures and coordinate actions across government levels, sectors, and agencies if prioritized by the central government. For example, mobilization of multiple sectors facilitated mass poultry vaccination, with >85% of all poultry receiving the bivalent H5/H7 vaccine annually since 2017. (16) Nevertheless, intergovernmental coordination challenges remain. Improving data sharing and coordination between human and animal health sectors will facilitate a One Health approach to influenza, while enhancing communication between clinicians and public health professionals will improve early detection and the use of influenza vaccine and antiviral medications.

-

Seasonal influenza immunization infrastructure is critical for pandemic preparedness to allow efficient, rapid vaccination with pandemic vaccine. Despite China’s domestic seasonal influenza vaccine production capacity, influenza vaccine coverage in China is low (<2%) (17), even among high risk populations recommended for vaccination by China CDC. National policy to encourage influenza vaccine use may increase healthcare worker and public awareness of the vaccine, promote adult immunization infrastructure development, and better prepare China for the next pandemic.

-

In the past decade, China has increased its capacity to diagnose, manage, and treat avian influenza infections. Gaps remain in testing and treating patients with seasonal influenza. Moreover, during the severe 2017–2018 influenza season, the healthcare system was overwhelmed due to insufficient clinical surge capacity, and several cities reported antiviral medication shortages. Improving preparedness will entail upgrading hospital infrastructures, expanding antiviral stockpiles, building logistical capacity, and improving staff surge capacity. In addition, increasing influenza vaccination coverage and use of personal protective equipment among healthcare workers may protect frontline staff and prevent nosocomial infections.

-

Risk communication has improved since the 2003 SARS outbreak. During the H7N9 epidemics, China’s key government ministries, led by the State Council, collaborated to develop and disseminate H7N9 prevention and control messages through traditional and social media platforms. Government spokespersons provided timely, transparent information-sharing. The 2017–18 influenza season, however, revealed the need to strengthen risk communication about the intensity and severity of influenza seasons using influenza surveillance data.

-

During the past century, the world’s population has quadrupled and humans and animals have become increasingly connected through travel and global supply chains. A novel influenza virus can spread internationally within hours. Pandemic preparedness in China is critical because of its population size, robust poultry industry, and circulating avian influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. In the last decade, China has become a global leader in influenza detection and collaboration, actively engaged with WHO and the international health community. China is ready to undertake greater responsibility for the early detection of and response to influenza threats with pandemic potential. Enhancing China’s pandemic preparedness requires government commitment to update the national influenza pandemic preparedness plan, increase investment in China’s public health and healthcare systems, promote seasonal influenza vaccination, improve medical care, countermeasures and risk communication during influenza epidemics, and facilitate multisector communication and coordination to promote a One Health approach to influenza.

HTML

1918 Influenza Pandemic

Early Influenza Surveillance Capacity in China 1949–1954

1957 Influenza Pandemic

1968 Influenza Pandemic

Improvement of Influenza Surveillance in China, 1977–2000

Public Health Capacity Development Triggered by Novel Respiratory Diseases, 2002–2005

2009 H1N1 Pandemic

CNIC became a WHO Collaborating Centre for Influenza in 2010

Detecting and Responding to Avian Influenza A(H7N9) 2013–2018

Progress and Remaining Challenges in Pandemic Preparedness and Response

Political Commitment

Multisector Coordination

Influenza Vaccination

Medical Care and Countermeasures

Risk Communication

| Citation: |

Download:

Download: